About

The story of the Luisenburg rock labyrinth in Wunsiedel, Germany starts 240 million years ago, when lava flowed into the mountainous area. After the lava solidified and crystalized, erosion began to slowly break down the softer rocks and round off the hard granite leaving the boggy, woodland area strewn with formations of giant rocks and boulders, caves and plateaus.

Fast forward to 1790 when the landscaping craze of the early romanticism swept across Europe and the good people of Wunsiedel began draining the area, laying down paths and carving out stairs, slowly turning the boggy and rock filled forest into a romantic wonderland inspired by English gardens.

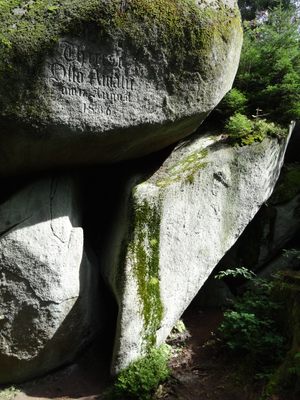

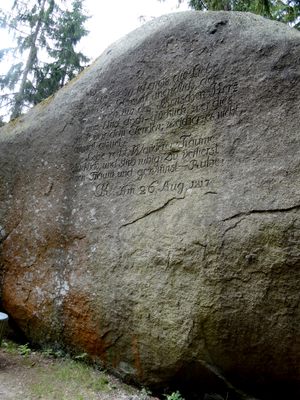

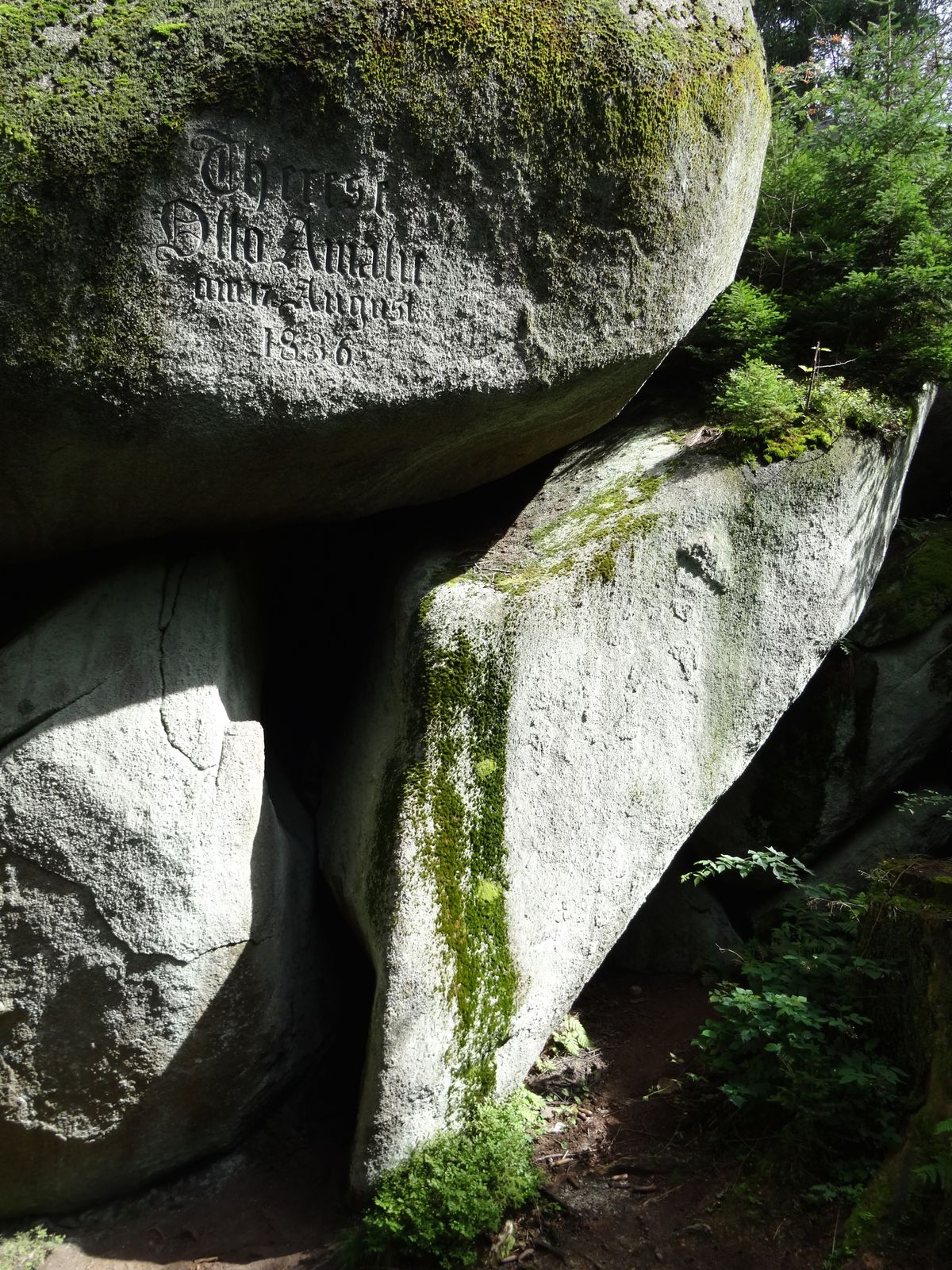

The labyrinth project was funded by a regular visitor to the area's baths, Baron von Carlowitz from Regensburg, who also penned several of the rock inscriptions. This first part of the maze ended by the ruined castle and one-time robbers' den called Luxburg, which had been crumbling away amongst the rocks and boulders since at least 1352. In dramatic style, the ending of the labyrinth was marked with the words "This Far and no Further" carved into the rock.

In 1805, Frederick William III of Prussia came to visit the area for the first time since its annexation to the Prussian Crown and the mayor of nearby Wunsiedel Dr. Johann Georg Schmidt renamed Luxburg and surrounding area "Luisenburg" to honor the Prussian Queen Louise. On this occasion, the mayor also initiated the expansion of the maze, however it was temporarily halted by the Napoleonic occupation between 1806 and 1810.

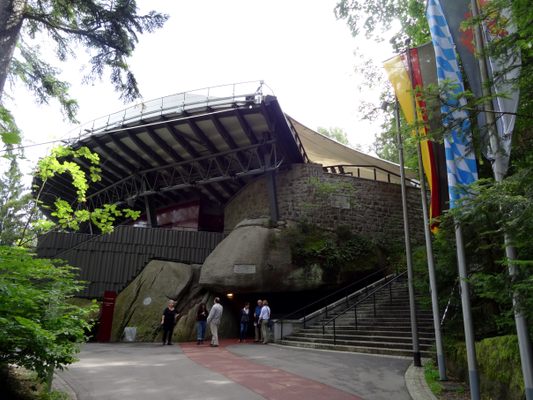

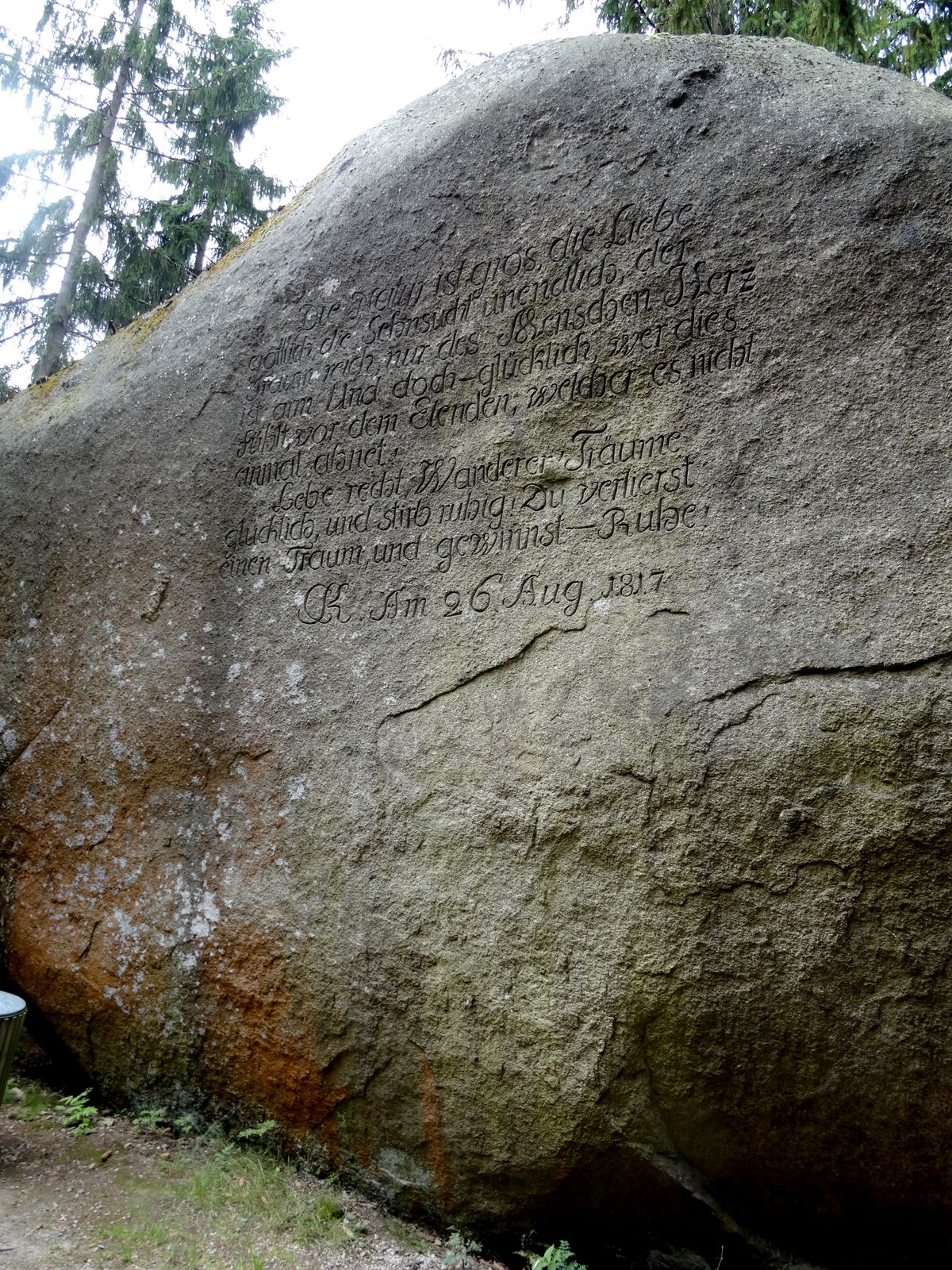

After the war, three of Schmidt's sons, including Florentin Theodor Schmidt, who made his fortune trading in sugar, picked up the work of expanding the labyrinth. (Today several rocks at Luisenburg bear the inscription FTS.) Luisenburg was completed in 1820, featuring paths, benches for resting, numerous poetic inscriptions in the granite rocks, and an open air theatre. Rock formations were given enticing names like The Three Brothers, Napoleon's Hat, Sugar Loaf, and Devil's Staircase.

The open air theatre has been expanded and modernized on several occasions and to this day hosts outdoor plays in the summer season. Allegedly, these plays predate the rock maze—the first plays are said to have been staged at the natural cave theatre by the entrance as early as 1665 as part of the Margarethenfest, thus making the Luisenburg Festspiele the oldest existing outdoor theatre in Germany.

The labyrinth gets more difficult to navigate as you progress. In the beginning the paths are wide, you can make little detours to explore vantage points and small caves, some of which are covered in a luminous moss. But as you get nearer to the climax of the maze you have to squeeze through narrow passages, climb steep, wet stairs and the ground can be soggy. Once you reach the end, you are led back out along other paths and walking gets easier as you've finished your adventure. Your return to civilization is tranquil affair: One of the first inscribed rocks you encounter on your way back bear the words "Ego in Arcadia — I am in Utopia."

On your way towards the exit, you come across a seven-meter tall rock sat in a small pond. It's known as Insel Helgoland, named after the North Sea island of Heligoland. The island held a particular place in Schmidt's heart. As it was under English rule, the English used Heligoland as a harbor for smuggling sugar ,and thus made trading sugar with Germany possible despite a trade blockade imposed by Napoleon. The monolith is crowned by a wooden pagoda—the current one is a replica built in 2005 as part of a large scale renovation of the park marking the bicentenary of Queen Louise's visit.

Related Tags

Published

October 21, 2016

Sources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frederick_William_III_of_Prussia

- http://www.angewandte-geologie.geol.uni-erlangen.de/oberfrk3.htm

- http://www.bayern-fichtelgebirge.de/luise/index.html

- http://bildsuche.digitale-sammlungen.de/index.html?c=viewer&bandnummer=bsb00070157&pimage=00221&lv=1&l=de

- https://books.google.dk/books?id=A5g3WGt69p8C&pg=PA25&lpg=PA25&dq=Florentin+Theodor+Schmidt&source=bl&ots=tOSMq93T1E&sig=9dcuQDpfaAC30iNGbSQ91dYAt_0&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwixjLvYgdjPAhUEG5oKHTJ2Av0Q6AEIHDAA#v=onepage&q&f=false

- https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/H._J._Merck_%26_Co.

- https://books.google.dk/books?id=gEJBAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA208&lpg=PA208&dq=Baron+von+Carlowitz+wunsiedel&source=bl&ots=4a2TjPvcD9&sig=72c6MJgLFiABpAuWPXR-0Wx322A&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjm8JnrrNjPAhVhOJoKHdRwCyYQ6AEIJjAB#v=onepage&q=Baron%20von%20Carlowitz%20wunsiedel&f=false

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luisenburg_Rock_Labyrinth

- http://www.lfu.bayern.de/suchen/index.htm?q=luisenburg&wm=sub

- https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burgstall_Lugsburg