About

Tourists flock to Jodhpur to see the astonishing Mehrangarh Fort, a 15th-century bastion that looms over the city like a watchful parent. It’s enormous, perched on a hunk of rock that’s always in view. But just a stone’s throw away, another of Jodhpur’s monuments has a much lower profile, quite literally: The 18th-century Mahila Baag Jhalra, a subterranean stepwell that’s so unobtrusive it’s almost impossible to see, even when you’re standing a few feet away.

The lovely, multi-layered and multi-hued structure appears in no guidebook, on any tour, or in hardly anyone’s consciousness. But it wasn’t always that way. Stepwells were sophisticated water-harvesting structures built throughout India starting around 600 CE. There were thousands of them, each providing continual, year-round access to water that fluctuated dramatically between the dry and the rainy seasons. Long flights of steps could reach the ground water at its lowest, and as water rose during monsoons, the steps would submerge, sometimes entirely. This nifty, efficient system continued for over a millennium, gradually waning by the 19th century.

Despite their past prominence, stepwells fell completely off history’s grid and today, most are entirely unknown, even within India. Modern water pumps and plumbing rendered these unique subterranean marvels obsolete, and now the vast majority are decrepit, anonymous, often filthy, and generally heartbreaking. Some are well-maintained by the government and attract tourists, but not the graceful Mahila Baag. It lies utterly forlorn just outside the old walls of Jodhpur next to a noisy road, crammed between shops and dwellings, obscured by motorcycles and electrical lines. Passersby are oblivious, and it’s nearly unimaginable that Mahila Baag Jhalra was originally embedded in an elegant garden (baag).

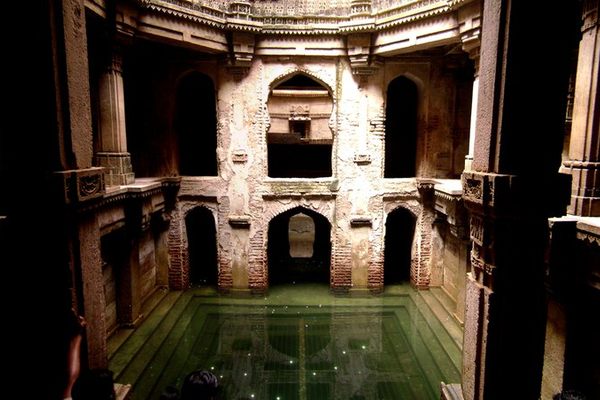

The visual chaos and din only add to the excitement of discovery when standing along the edge of this unexpected treasure. A dazzling array of pyramidal stairs is disorienting, as is the experience of looking down into architecture, not up at it as usual. It’s even more disorienting to start the descent, as though entering a drawing by M.C. Escher. You must pick your way carefully among the befuddling combinations of stairs. Paying attention is crucial.

The stepwell is allegedly named for Mayla, a beautiful and wealthy concubine who is said to have commissioned it. Through the centuries, Mayla evolved into Mahila, which means “lady” in Hindi, and compared to the brutal-looking fort, this diminutive, inconspicuous structure seems especially dainty. It’s a multi-hued layer cake of stone, built from the pink sandstone seen in so many of Rajasthan’s monuments. There are small pavilions at each corner that were shady retreats in scorching summers when cooling off by the water’s edge must have been appealing. Now, the water is clogged with trash, even though hardy fish can be seen swimming under the surface.

Luckily, there’s much to be hopeful for in Jodhpur these days. For hundreds of years the city was renowned for its advanced water harvesting systems, which Mahila Baag Jhalra was part of. Now, the city has again become a hotbed of conservation efforts, with stepwells and other water bodies being revitalized all over the city. Mayla’s garden retreat may yet have its day.

Victoria Lautman is an arts and culture journalist with a focus on India. Her book, The Vanishing Stepwells of India, was published in 2017 by Merrell (London). Follow her @victorialautman.

Related Tags

Delhi and Rajasthan: Colors of India

Discover Colorful Rajasthan: From Delhi to Jaipur and Beyond.

Book NowPublished

April 2, 2018