About

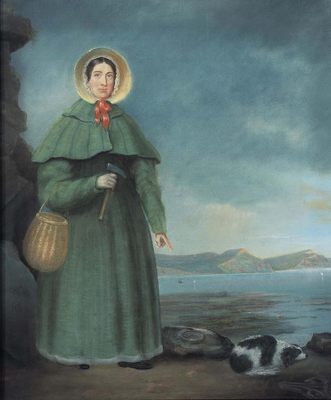

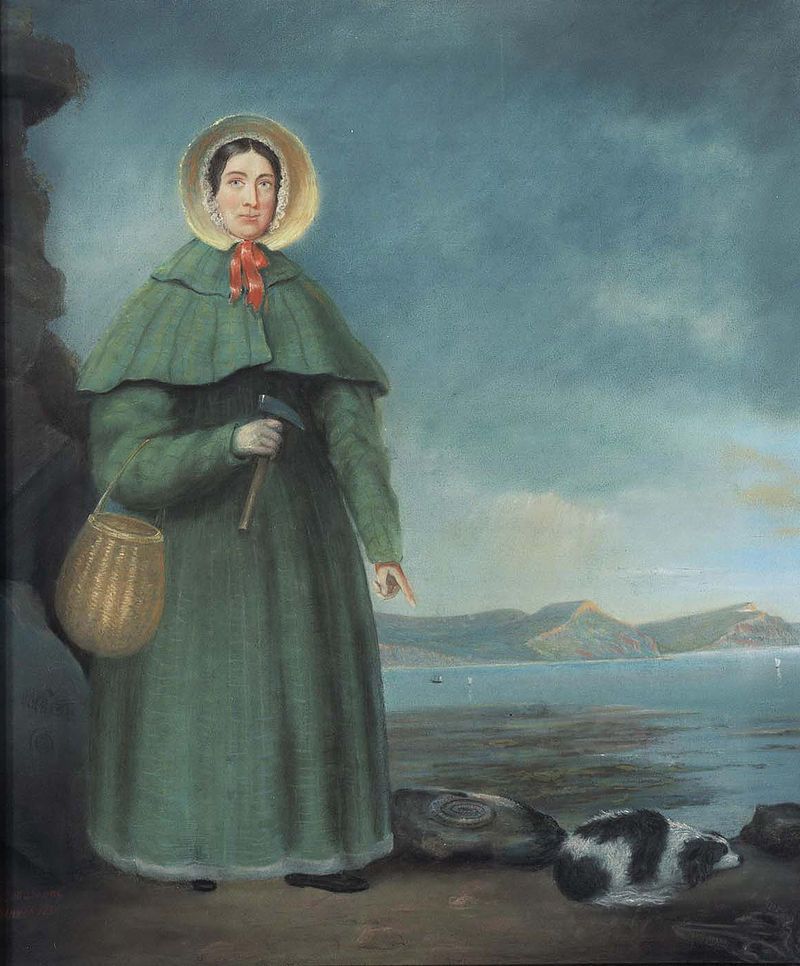

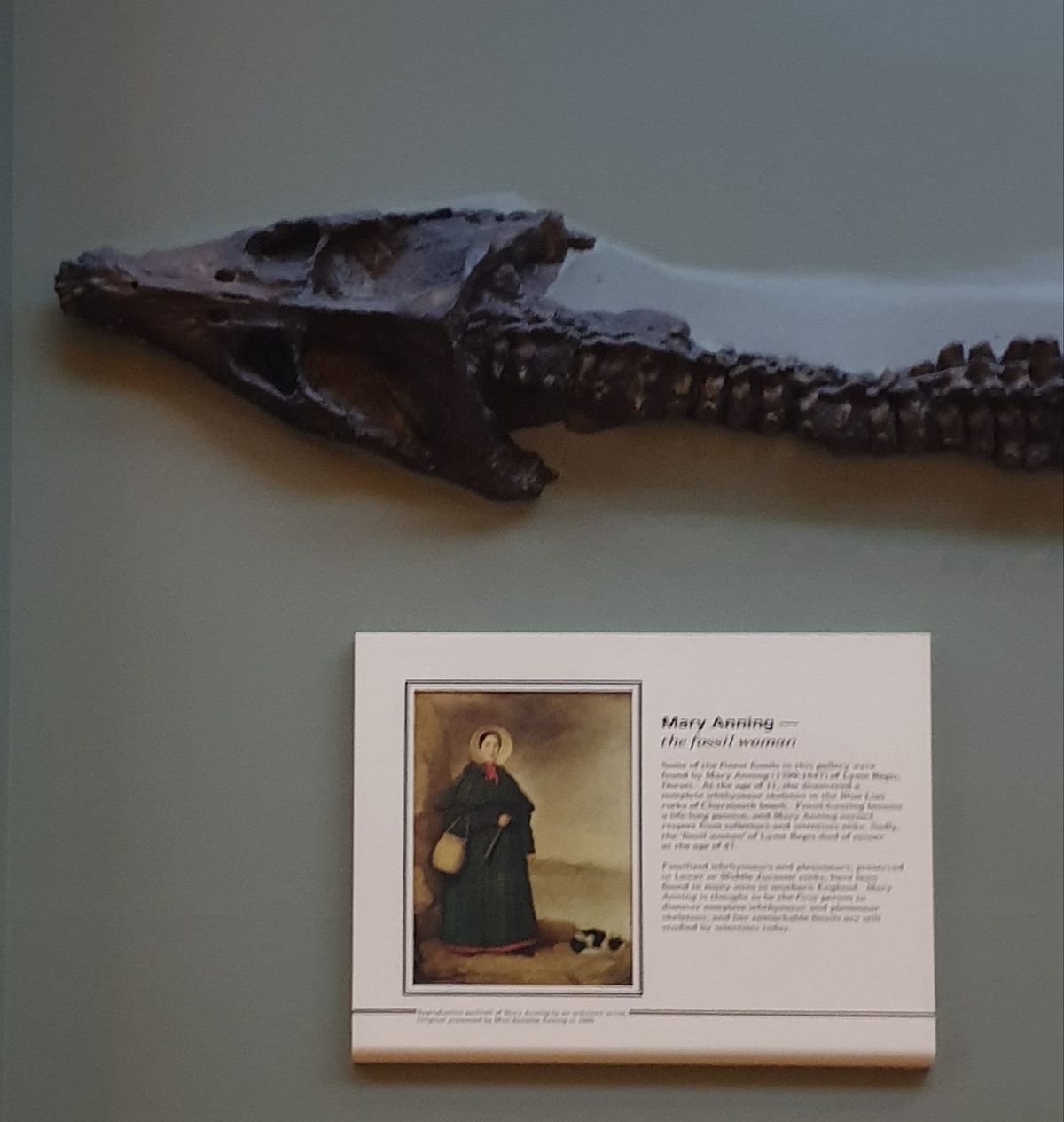

Mary Anning was born to a poor family at the turn of the 19th century in the English seaside town of Lyme Regis. There was little to indicate she would one day help revolutionize science and humankind’s understanding of the natural world.

According to local legend, Anning’s curiosity and a knack for unearthing fascinating fossils had a rather unconventional cause. When she was only a year old, Mary was struck by lightning while attending a traveling equestrian event. The person holding Anning perished, but the young child somehow survived. The Anning family often retold this event and credited it with improving her health and developing her high level of intelligence.

Anning’s love of collecting fossils began early in life. She accompanied her father Richard, a carpenter who collected fossils as a hobby, to search for them along the seashores. Tragically, her father was critically injured after falling off a cliff. He then developed tuberculosis, from which he was unable to recover, and died when Anning was only 11 years old.

Despite the tragic loss, Anning continued her fossil hunting trips, walking miles along the coast to find new specimens. On one trip that was to mark the rest of her life, she encountered a tourist who was so impressed by a fossil ammonite she had found that he bought it from her for half a crown.

This first sale inspired Anning to begin collecting fossils to sell commercially to tourists and scientists, and, as a result of her entrepreneurial venture, she soon developed a thriving business that helped keep her impoverished family from destitution.

In 1811, Anning unwittingly entered the world of science at only 12 years old when she and her brother discovered the gigantic skeleton of what they at first thought was a monster. News of the fossilized remains quickly came to the attention of the scientific community in London. Some contended that the bones belonged to a crocodile that had been washed accidentally to England in a storm or during the biblical floods, while others believed they belonged to an unknown deep-sea fish. It was years before the bones were recognized as those of an ichthyosaur, a prehistoric marine reptile.

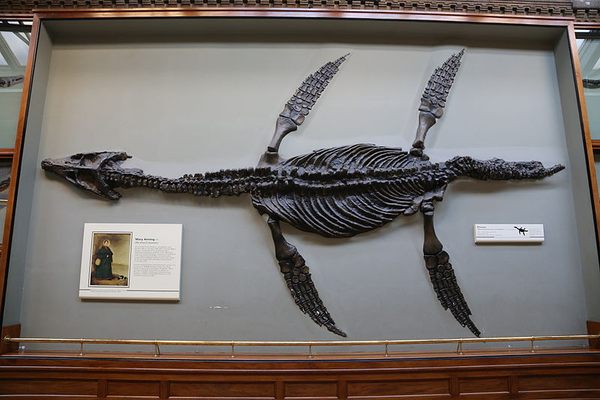

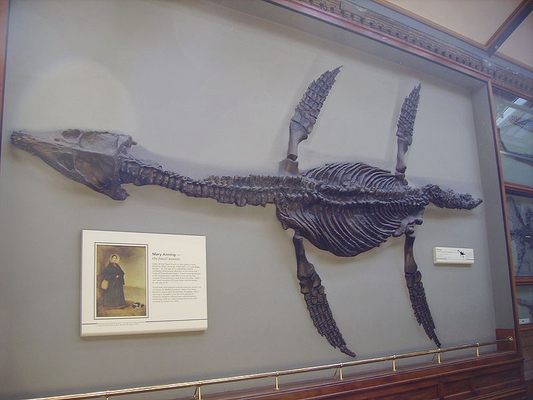

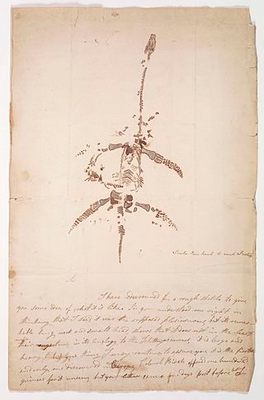

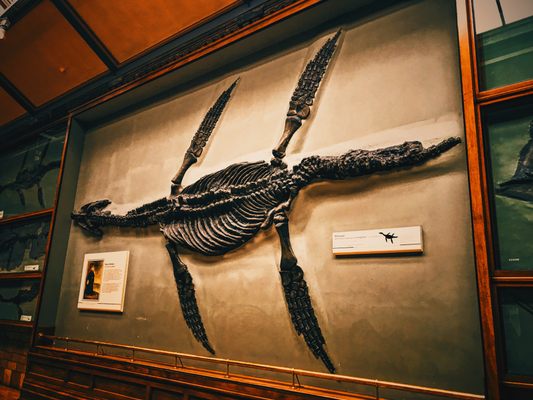

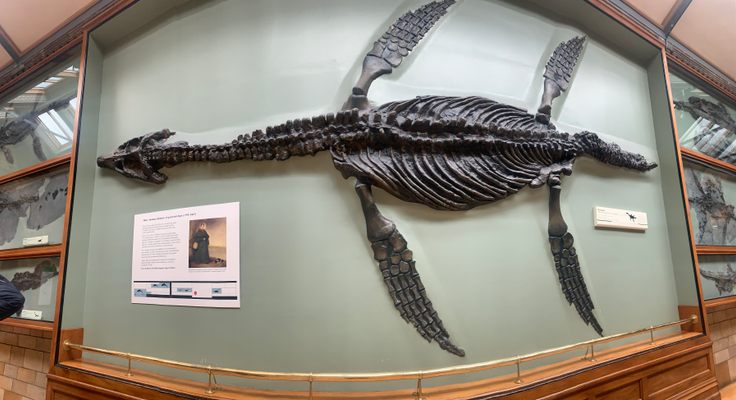

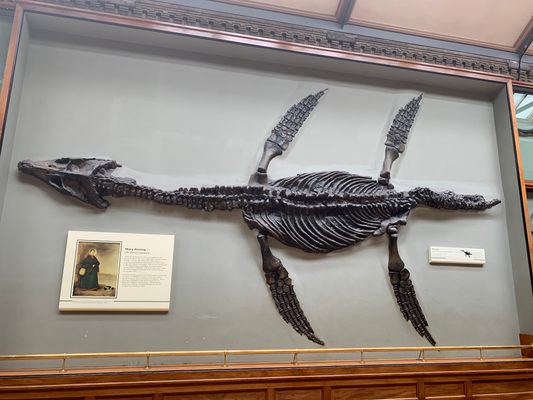

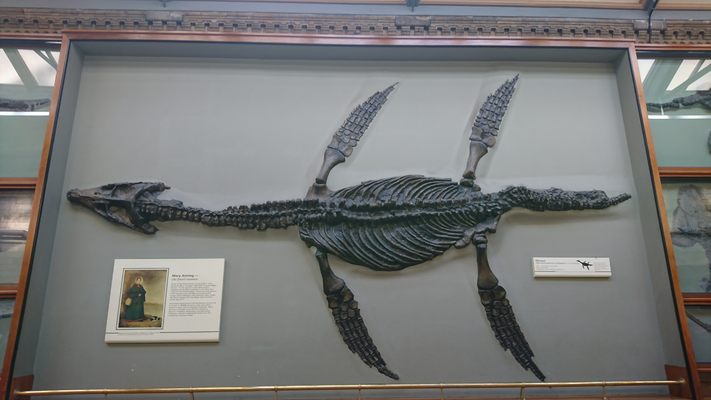

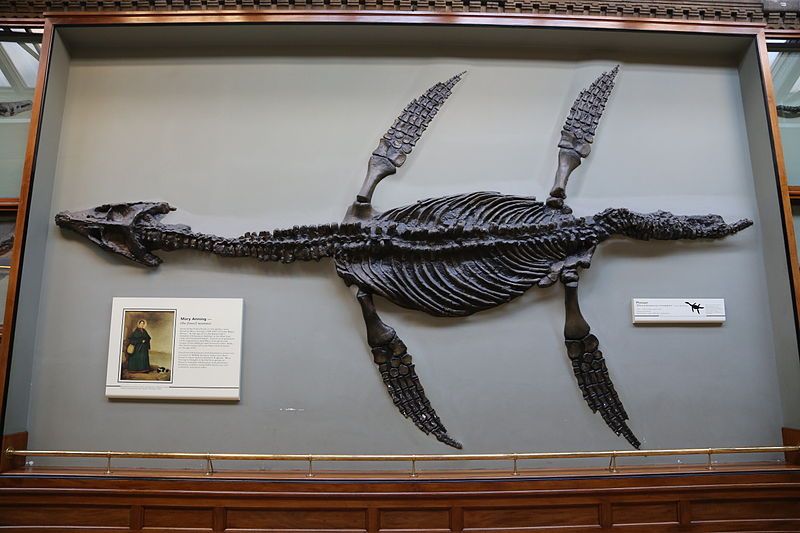

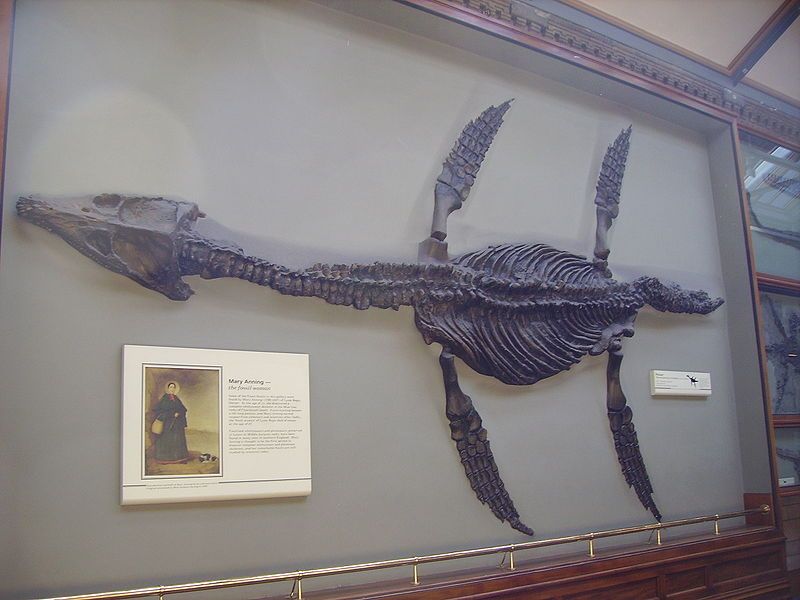

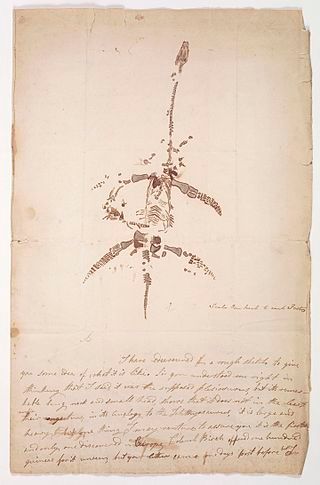

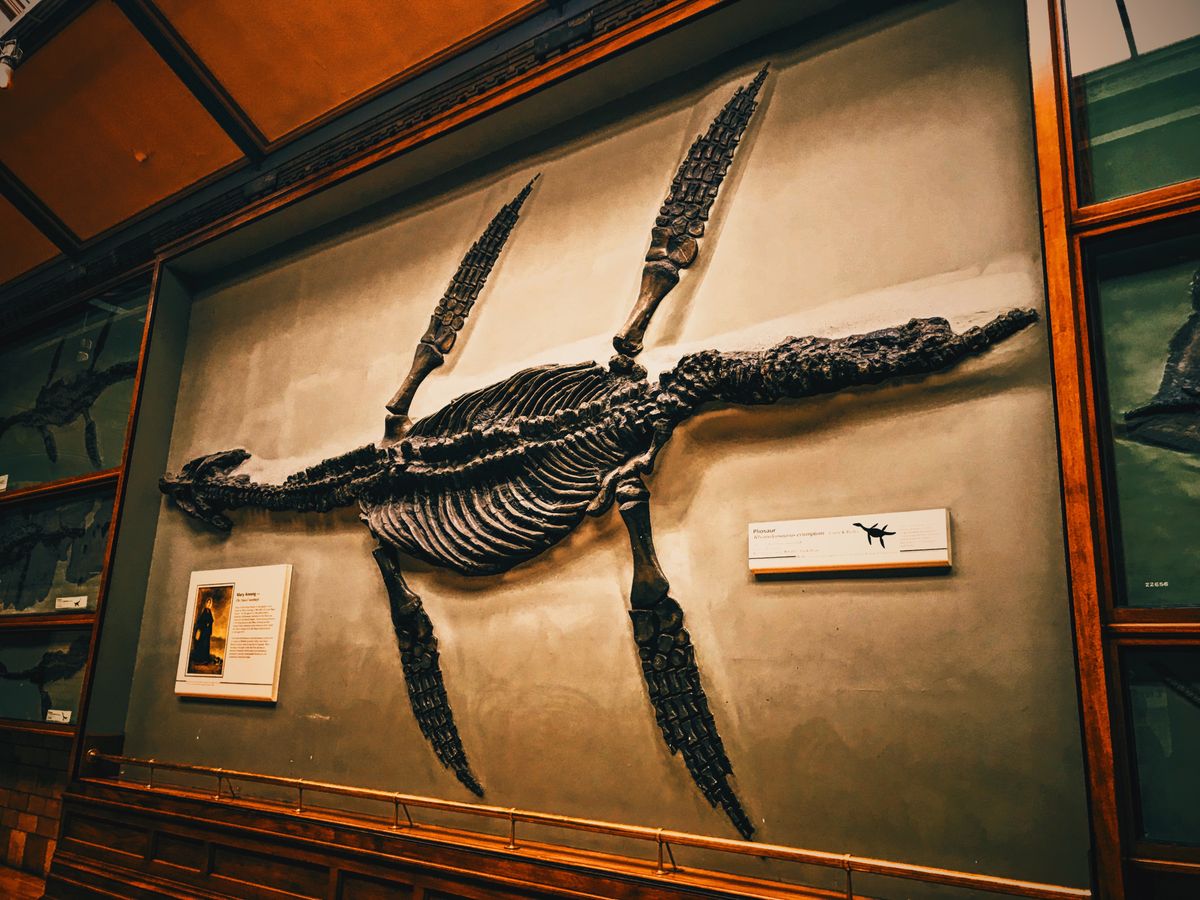

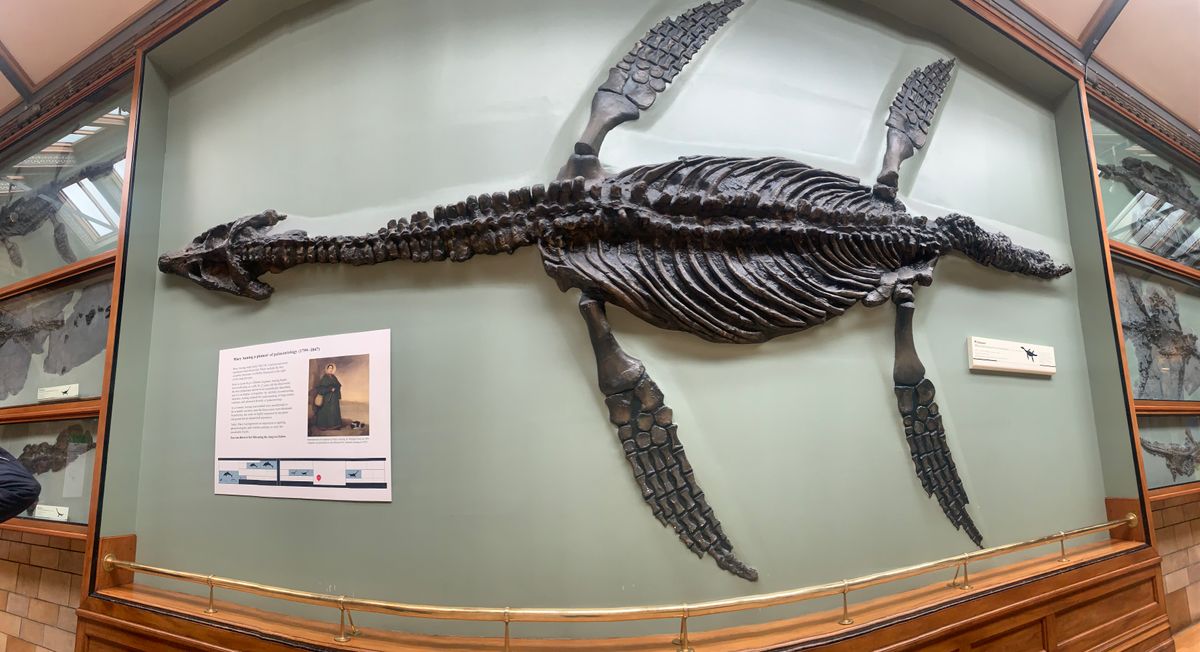

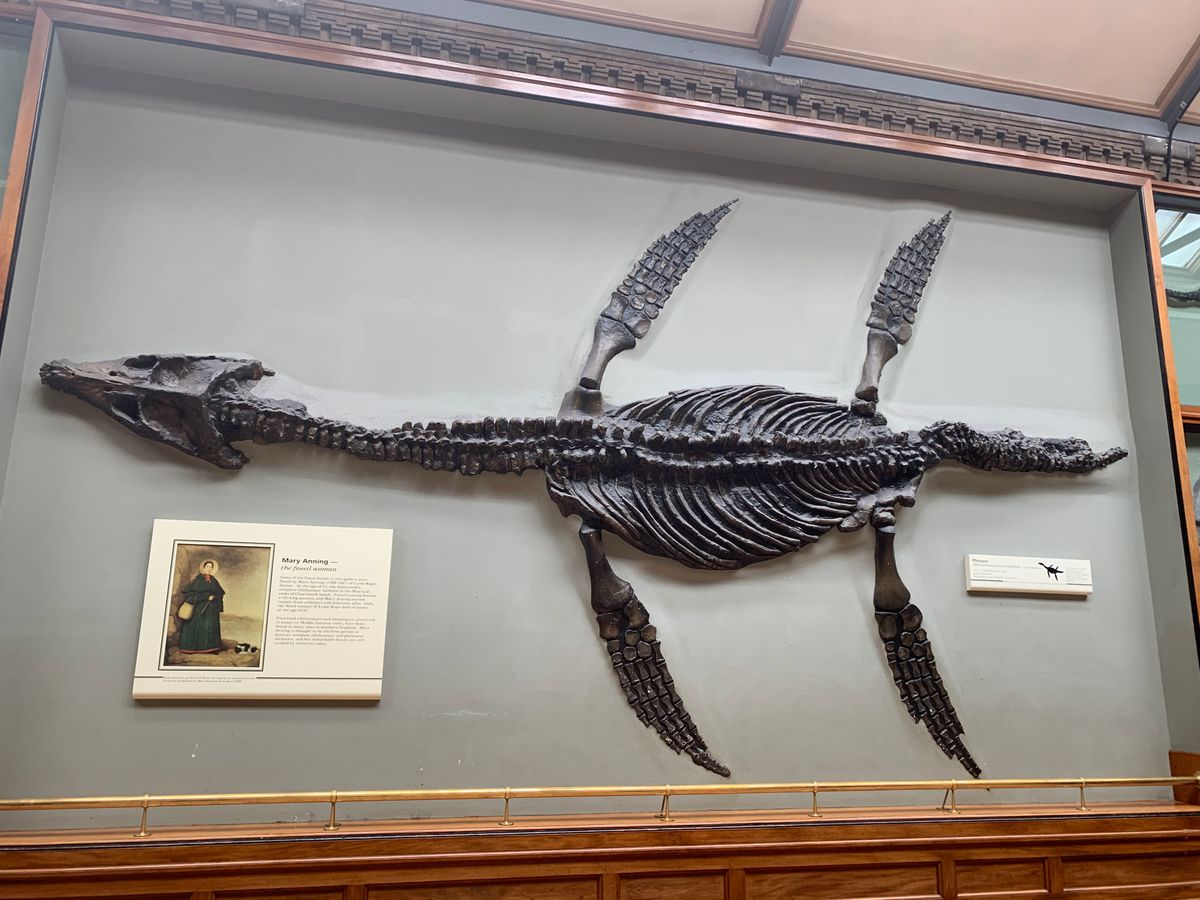

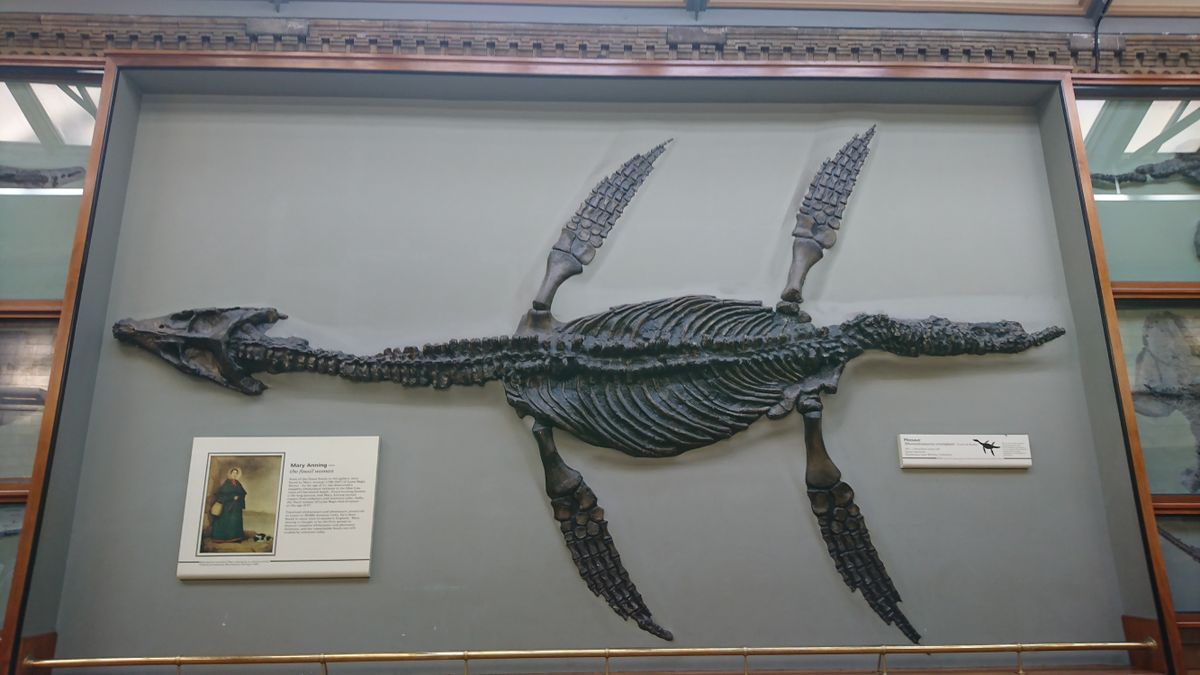

In 1823, Anning discovered the bones of another gigantic reptile-like creature, which caused an even bigger sensation: a plesiosaur. The news of this discovery spread quickly throughout the scientific world, and the remains were brought to the Geological Society of London and became the subject of scientific debate, to which Anning was not invited. The famous French scientist Georges Cuvier, known as “the father of paleontology,” inspected the bones and first concluded that they were fake before eventually admitting his error and recognizing their authenticity.

Over the years that followed, Anning made further discoveries of fossils that revolutionized science. However, in spite of her phenomenal contributions, Anning was rarely recognized officially for her discoveries, which were instead credited to the wealthy “gentlemen scientists” who bought the fossils. She was also consistently refused entry to the Geological Society because she was a woman.

It was only in the last years of her life that Anning received the recognition and praise from the scientific elite that she so clearly deserved. She was finally given an annual payment by the Geological Society and was formally recognized in scientific papers. But recognition came a bit too late: Anning died of breast cancer in 1847 in considerable financial difficulty, despite her contributions to scientific understanding.

In time, Anning’s discoveries would provide paleontological evidence for scientists such as Charles Darwin, Alfred Russel Wallace, and Thomas Henry Huxley to develop the theory of evolution that would challenge the dominant biblical story of creation.

Today, you can see Anning’s plesiosaur, which is displayed in London’s Natural History Museum.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

The fossilized skeleton of the Plesiosaurus and a small portrait of Mary Anning with more information can be found in the green zone of the Natural History Museum in the fossil hall walkway off Hintze Hall, where you may see other fine specimens of long-extinct species such as a giant ground sloth and Ichthyosaurs.

It's the largest fossil on the wall opposite the 'Dippy the Dinosaur' entrance.

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

November 30, 2018