About

The French Revolution brought with it a staunchly anti-clerical leadership: By 1794, the authorities shut down every church in the country and prohibited Nativity scenes. In an attempt to cling on to their religion, many French people began to construct makeshift Nativity scenes out of papier-mâché, cloth, bread, and anything they could get their hands on — even at the risk of the guillotine.

Just three years later, artisan Jean-Louis Lagnel of Marseille turned this figurine-making tradition into an enterprise, by selling locals little figurines made out of clay (rather than wood or plaster, to make them affordable). And from this bold, counter-revolutionary idea, the figurine-making business grew and developed.

In 1826, the figurines became named “santons,” and by the 20th Century, Thérèrese Nevau became the first to fire up the santons in a clay oven in order to make them last longer. He declared himself a “santonnier,” manufacturer of santons, and soon enough his home city of Aubagne — which had a history in the clay industry dating back to Roman times — became the international center for santon-making.

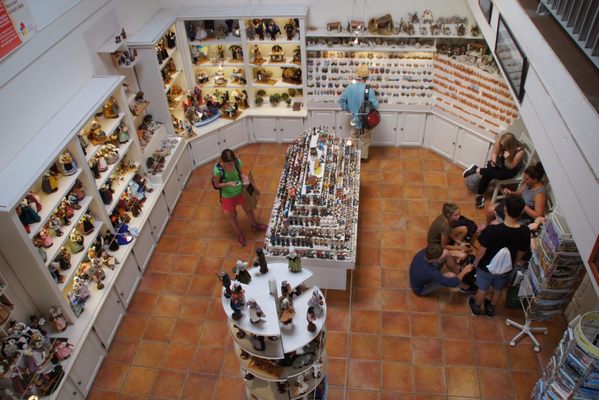

This form of craftsmanship has lived on in Aubagne, where you'll find a multitude of family-run santon shops where the skills of santon-making are passed down from parent to child. Visitors to Aubagne can witness these processes in real life by visiting Santons Maryse Di Landro, a functioning santon workshop and museum.

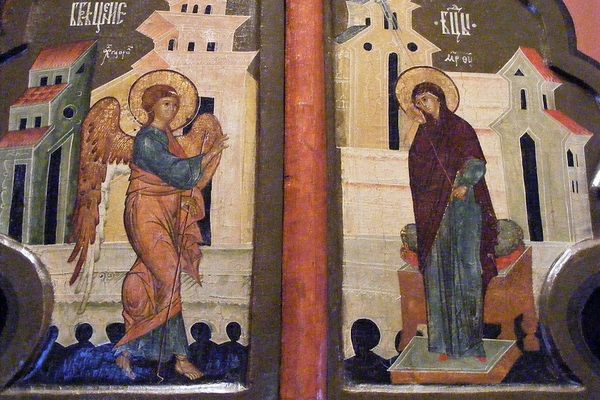

Santons Maryse Di Landro uses the entire first floor to manufacture the figures, but its second floor has been turned into a unique museum of santons. Featuring 400 original figurines, the museum depicts scenes from the Bible, French history, and daily life in Provence. A walk through the museum is both an eerie and humbling experience. Santons for sale range from a few euros to hundreds, and are most commonly purchased by residents of Provence during Christmastime.

Related Tags

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

July 13, 2016