About

At the entrance to the ancient city of Ypres stands an arch inscribed with the names of British and Commonwealth soldiers who were killed in the battles to defend the Ypres Salient in World War I.

The city of Ypres, historically a center of the cloth trade, has been fortified since medieval times. The original fortifications were improved by French engineer and military leader Vauban in the 17th century. Today, the most interesting and touching part of the ramparts is the Menin Gate, marking the departure point from which hundreds of thousands of soldiers left to the front lines of Ypres Salient, never to return.

Ypres, caught in the path of the German line of attack, became a base of operations in the Great War and, ultimately, another of its victims. The Ypres Salient was a bulge in the front lines of the battle that formed around the stronghold at Ypres, meaning that the soldiers defending the area were effectively surrounded on three sides by enemy forces.

The battles that raged near Ypres between 1914 and 1918 saw the start of trench warfare, the introduction of tanks and heavy machine gun fire, and the use of poison gas. Tens of thousands were left dead at the end of each major battle.

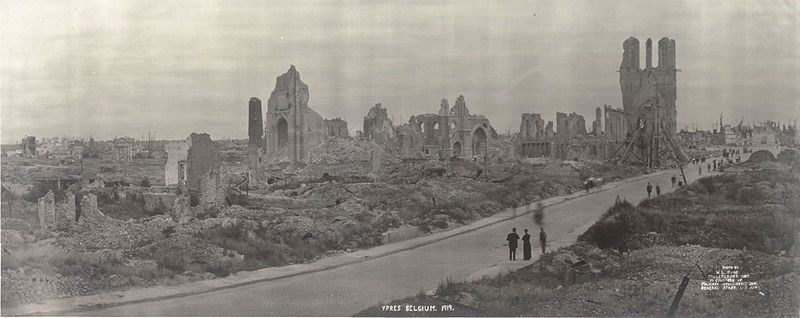

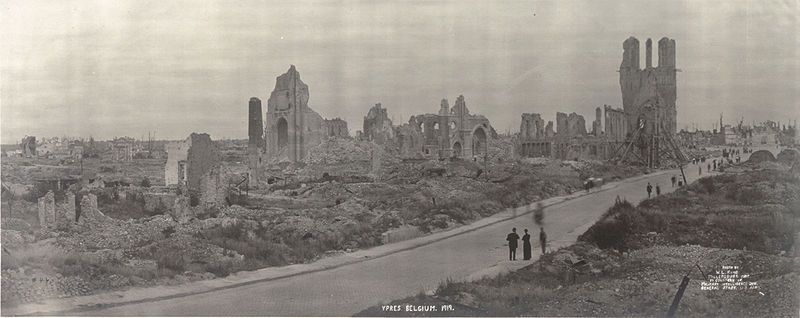

Ypres itself was razed nearly beyond recognition in the First Battle of Ypres in 1914, and again in the Second Battle of Ypres a year later. In November, 1914, the magnificent Cloth Hall, symbol of the city, was set ablaze. By 1919, Ypres was a city of rubble. The Cloth Hall, the cathedral, and the medieval center of town that visitors now enjoy are complete recreations paid for by German war reparations, and modern building-dates can be seen on the numbers on the fronts of the houses.

Today, the countryside around Ypres is dotted with vast cemeteries to the fallen, alongside pillboxes and the remains of trenches, still visible after nearly a century.

The triumphal arch that now stands at Menin Gate was designed by British architect Reginald Blomfield in 1921. The barrel-vaulted main passage for traffic honors 54,896 Commonwealth soldiers missing in action with their names engraved into the walls. So huge was the number of missing that 34,984 British soldier's names which would not fit in the Menin Gate had to be listed elsewhere, now located in a second memorial at nearby Tyne Cot, and the names of missing New Zealand and Newfoundland soldiers are listed at separate national memorials. The lions that adorn the memorial are the symbols of both Britain and Flanders.

At 8 p.m. every evening, volunteer buglers from the fire brigade assemble under the Menin Gate to sound the "Last Post" in tribute of those who fell, so the city may live. Since the first ceremony on the 3rd of July, 1928, the only time the ceremony was not held was during German occupation in World War II, when the ceremony was temporarily moved to Brookwood Military Cemetery in Surrey, England. In fact, the very evening the city was liberated, despite heavy fighting still occurring in other parts of the city, the ceremony was brought back to its proper place.

Please note that applauding at the end of the ceremony is frowned upon, as it is a very solemn occasion. Instead, the reverberating words "we will remember" provide those who attend with a truly haunting sound, one that stays alive in the memory for a long time after the ceremony.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

At the end of the right hand street next to the courthouse on the marketplace.

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

July 5, 2010