About

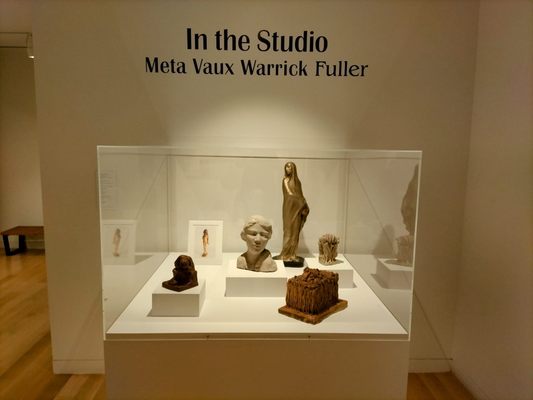

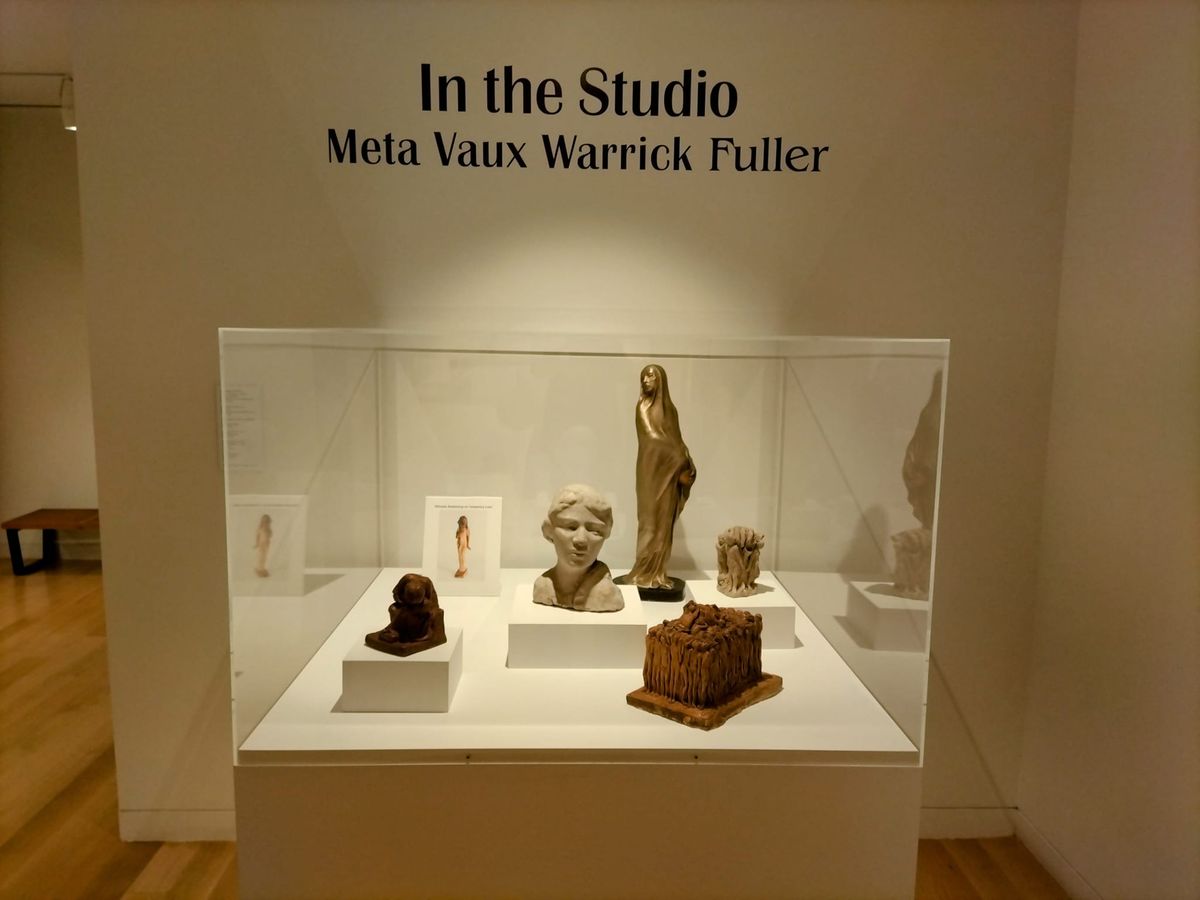

The Framingham Centre Common is dotted with historical buildings, including the one that houses the Danforth Art Museum. Although not as large or renowned as other art museums near the Boston area, the Danforth has something in their collection no other museum has; the largest collection of works by Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller who was one of the first Black American female sculptors and the first artist to be commissioned by the U.S. government to do a series of dioramas on African-American history.

Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller was born in Philadelphia in 1877 to a middle-class family. Her mother was a beautician and her father was a barber. During the Reconstruction era, many formerly enslaved people moved north, and Philadelphia became home to a vibrant Black community. Her parents were able to find success with their creative talents and Warrick was educated in art, music, dance, and horseback riding.

Warrick’s artistic career began when one of her high school projects was chosen to be displayed at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Afterward, she was given a scholarship at the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art, where she rejected more traditional feminine artistic themes to focus on chronicling the Black experience in the United States. After graduating in 1899, she traveled to Paris, where she studied under the tutelage of Raphaël Collin at the Académie Colarossi and the École des Beaux-Arts. Due to racial discrimination, the American Woman’s Club of Paris refused to give her lodging, though she had made reservations beforehand. Thankfully, another prominent Black American artist and family friend, Henry Ossawa Tanner, provided her with lodging and introduced her to his friends.

Warrick continued to hone her skills as a sculptor. She was deeply influenced by Auguste Rodin, and became his protégé in 1902. Her sculptures were displayed at galleries in Paris, drawing in crowds who praised her works. While in Paris, Warrick also met W.E.B. Du Bois, who became a lifelong confidant and friend. He encouraged her to draw inspiration from African and Black American themes in her work.

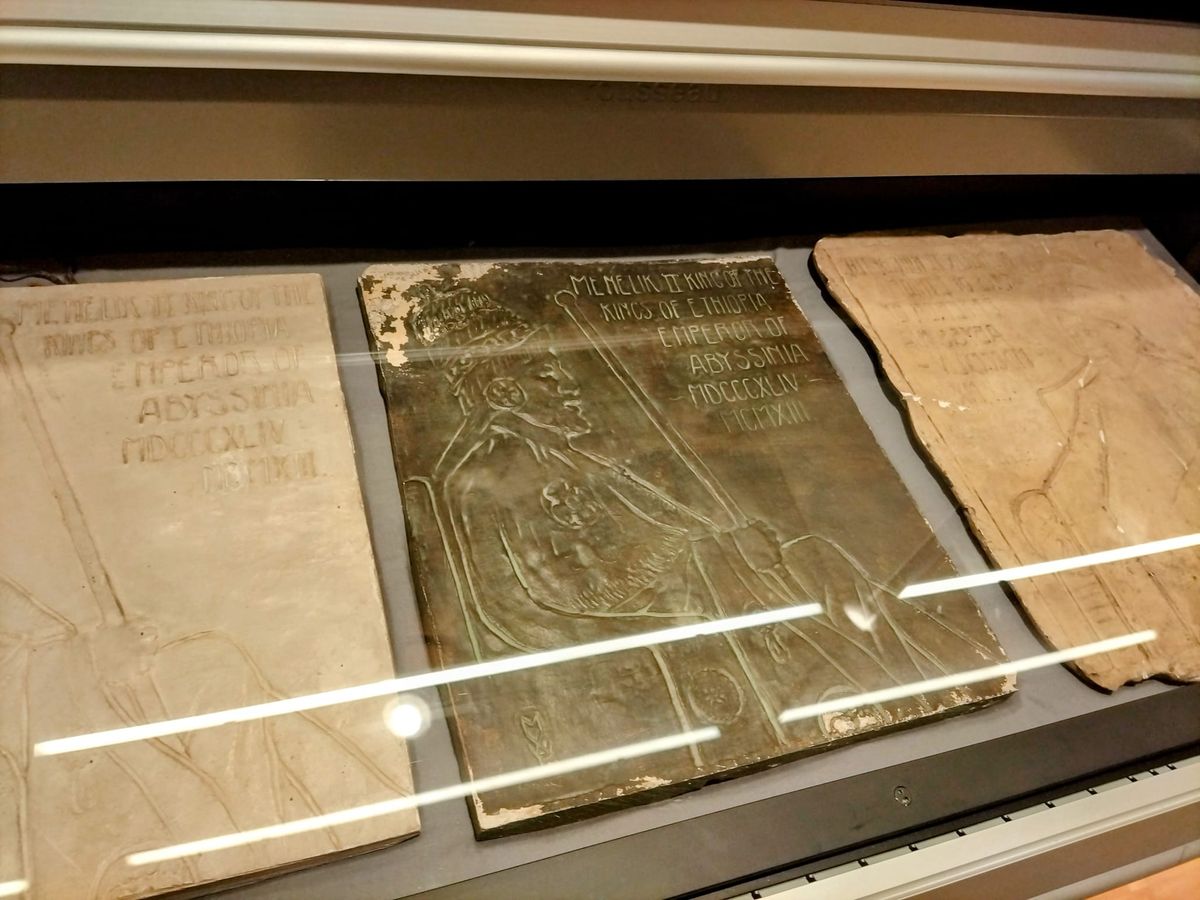

When Warrick returned to Philadelphia, much of her work was shunned by the upper-class members of the city. They saw her sculptures as grotesque, foreign, and unappealing. But her work depicting the suffering of Black subjects resonated strongly within the African-American community. Warrick became the first African-American woman to receive a U.S. government commission. For the Jamestown Tercentennial Exposition of 1907, she created sculptures regarding slavery, African-American life during the colonial era, and the impact of the Civil War.

In 1909, she married Dr. Solomon Carter Fuller, an immigrant from Liberia and one of the first Black psychiatrists in the United States. They settled in Framingham, Massachusetts, becoming one of the first Black families in the community.

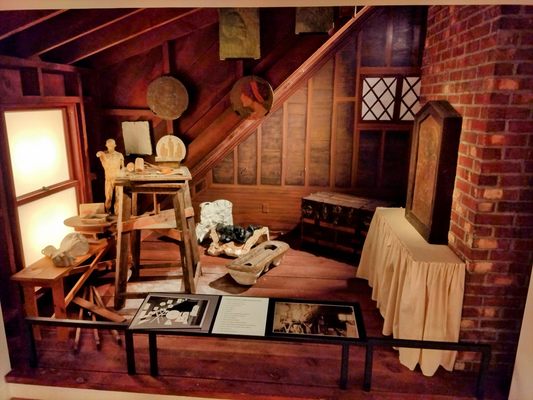

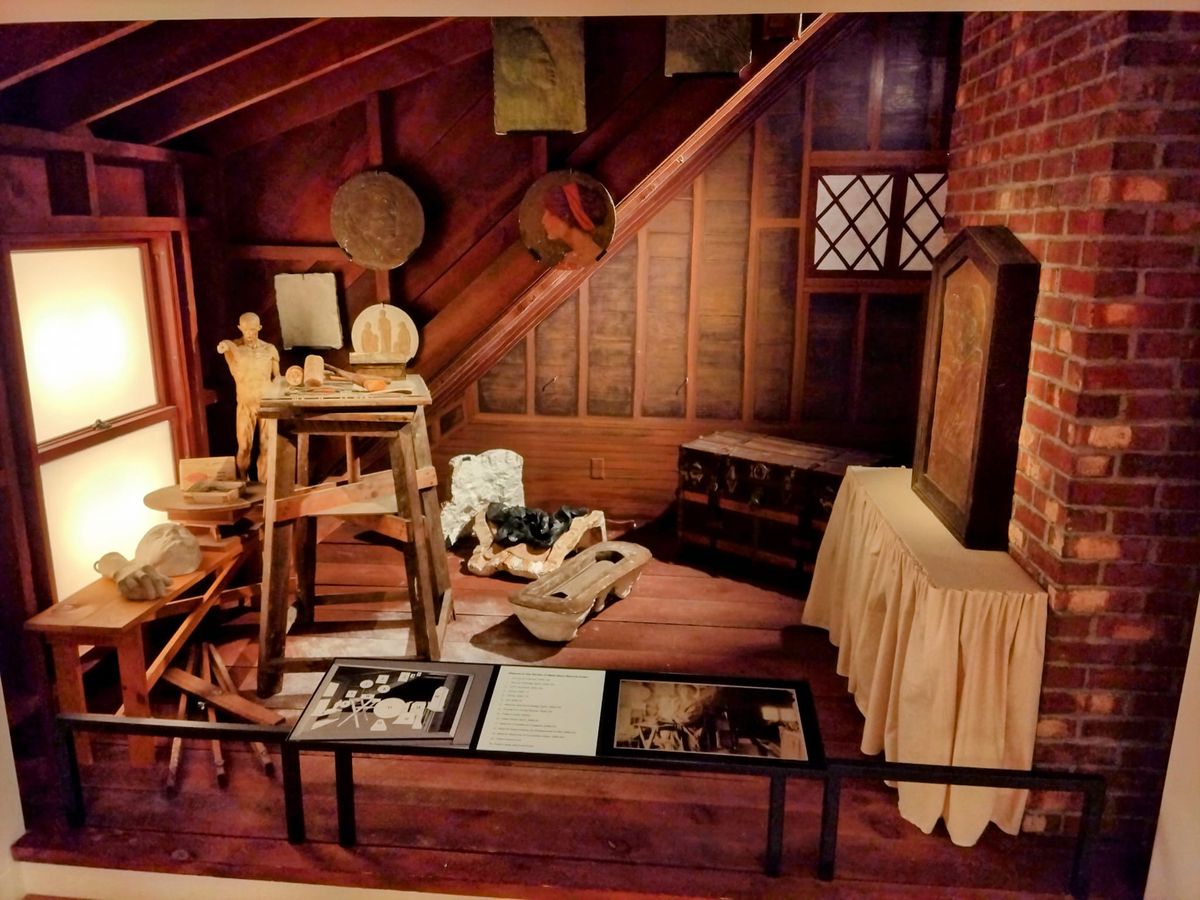

Fuller remained active in the artistic community. In 1910, a fire in a Philadelphia warehouse resulted in the loss of about 16 years' worth of her work. As a result, she built a studio in the attic of her home where she created art throughout the rest of her career. Fuller continued to use her art to address racial injustices in American society such as her sculpture dedicated to Mary Turner, a young, pregnant Black woman who was lynched alongside a dozen others in May 1918. Fuller also actively participated in the women’s suffrage movement but felt alienated and left soon after once it became evident Black women were not included in the vision of many of her fellow suffragists.

Fuller became an active member of the Harlem Renaissance Movement. In 1921, she exhibited at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts for the America’s Making Exposition which was intended to highlight immigrant contributions to American art. She created a series of sculptures titled Ethiopia, which depicted an African woman emerging from mummy wrappings like a chrysalis from a cocoon, symbolizing Black femininity and identity.

In addition to sculpture, Fuller also made significant contributions to painting, theater, and poetry. On the stage, she was a multi-faceted designer, director, and actress. She became involved in various African-American theatre and drama groups around the Boston area and joined the Allied Arts Theatre Group. She wrote about six plays under the pseudonym Danny Deaver.

After her death in March 1968, many of Fuller's accomplishments and contributions fell into obscurity, but they have received renewed attention since the turn of the 21st century. Her work can be found across the U.S., but the Danforth Art Museum has the largest collection, as well as a replica of her home studio and unfinished pieces.

Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller dedicated her life to pioneering both women and Black art in a time when both were heavily stigmatized by much of society. Her legacy is that of innovation, imagination, resilience, and fortitude, and her life story is certain to inspire so many others for generations to come.

Related Tags

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

November 20, 2024

Sources

- https://www.themagazineantiques.com/article/the-sculpture-of-meta-vaux-warrick-fuller/

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/2904066?origin=crossref

- https://www.nypl.org/blog/2024/04/11/meta-warrick-fuller-her-eyes-were-ever-opened-unto-beauty-and-all-world-was-art

- https://www.nypl.org/events/exhibitions/galleries/fortitude/item/16726

- https://library.uarts.edu/archives/alumni/warrickfuller.html

- https://www.uniquecoloring.com/articles/meta-vaux-warrick-fuller

- https://www.labiennale.org/en/art/2022/witchs-cradle/meta-vaux-warrick-fuller

- https://vc.bridgew.edu/hoba/27/

- https://anacostia.si.edu/collection/spotlight/thomas-hunster/jamestown-ter-centennial

- https://academic.oup.com/mississippi-scholarship-online/book/23826/chapter-abstract/185102864?redirectedFrom=fulltext

- https://nmaahc.si.edu/meta-vaux-warrick-fuller-ethiopia-1921

- https://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/she-was-trailblazing-african-american-sculptor-s2wd1i/14031/

- https://awarewomenartists.com/en/artiste/meta-vaux-warrick-fuller/

- https://www.themagazineantiques.com/article/the-sculpture-of-meta-vaux-warrick-fuller/

- https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/fuller-meta-warrick-1877-1968/

- https://reidhall.globalcenters.columbia.edu/metafuller