About

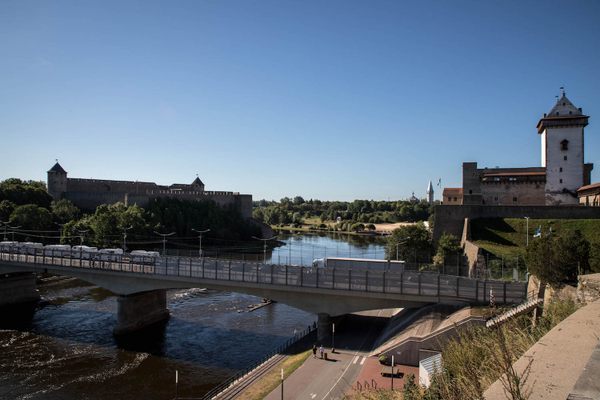

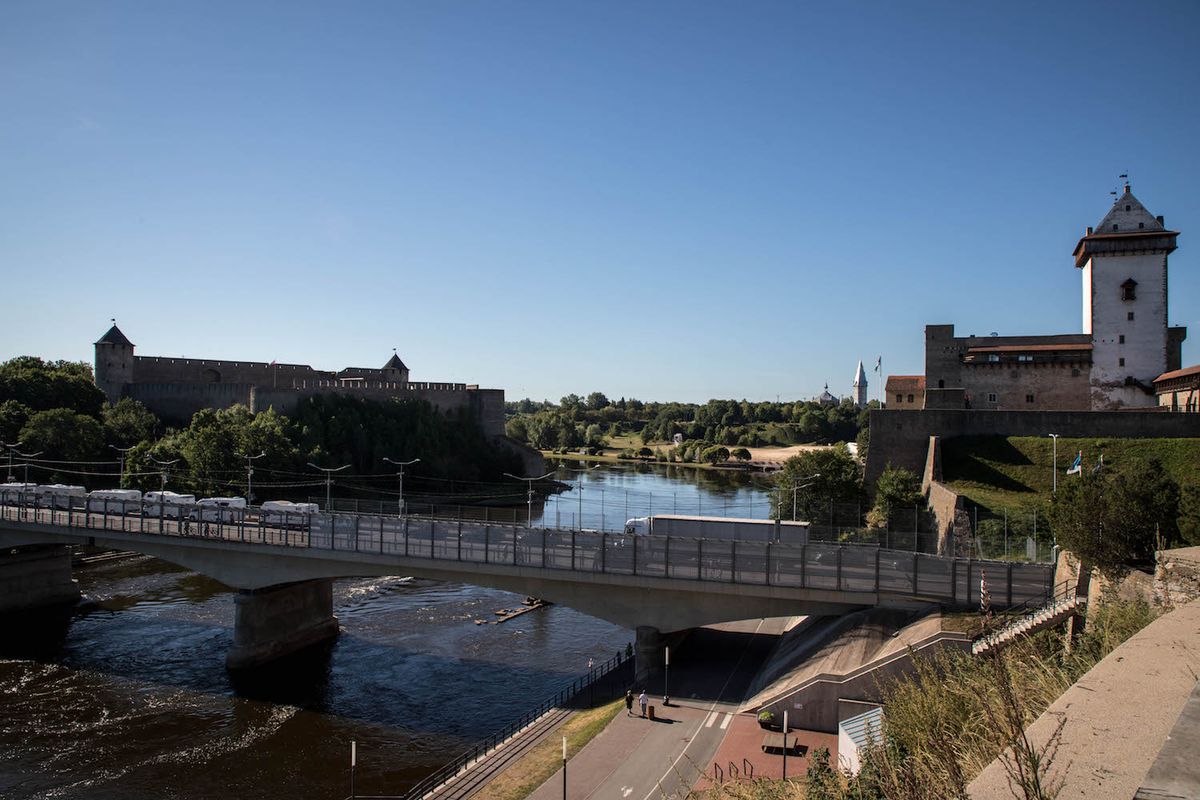

The city of Narva is located at the easternmost tip of Estonia. Only the waters of the Narva River separate it from Russia. On the far bank, the citizens of Ivangorod, Russia, can be seen going about their daily business there. This border is more significant than most in Europe, marking the boundary between the European Union and North Atlantic Treaty Organization on one side, and Russia on the other—yet here it feels bucolic, the far side almost close enough to touch.

During the Soviet occupation of Estonia (1944 through 1990), the border between the Estonian and Russian Soviet Socialist Republics was far more fluid than it is today. Many ethnic Russians wound up settling in Narva. A 2011 Estonian census showed that 87.7 percent of Narva’s citizens were ethnic Russians, while 95.7 percent spoke Russian as a first language. As a result, Narva, Estonia’s third largest city, can often feel far more Russian, in terms of culture, than its very progressive and Western-looking capital, Tallinn. And while many Soviet-era monuments have been removed in other Estonian cities, Narva has held onto its statue of one of the most divisive Russian figures of all: Vladimir Ilyich Lenin.

The Lenin statue originally stood in pride of place on Narva’s central square. Created by the famed Estonia sculptor Olav Männi, this bronze likeness was raised in 1957 and it was just one out of countless Lenins that decorated public spaces across the Soviet-occupied Baltic states. Following the restoration of Estonian independence in 1991, the majority of the country’s Lenin statues were taken down. In Narva however, with its predominantly ethnic Russian population and a city council that was then still largely composed of ex-communists, the 10-foot statue of Lenin remained in place until December 1993.

Crowds came out to protest the statue’s removal. One former city council member, Yuri Mishin, called it an “act of vandalism,” arguing that, “Lenin is loved in this city and most residents are very angry about this.” However the city’s new mayor, Raivo Murd, saw the statue’s removal as a chance to break with a complicated history. “In the past, when we tried to tell investors we were pro-reform, they took one look at that Lenin statue and said: ‘We don’t believe you,’” Murd was quoted as saying in the Associated Press

However, Narva’s mayor was willing to compromise to keep the peace. The removal team were asked to handle the statue with respect —not to place the cable around Lenin’s neck—and rather than destroy the statue or hide it in a warehouse, it was simply removed to somewhere less conspicuous: the Teutonic Hermann Castle, Narva’s most popular tourist attraction.

Built in the 14th century, today this riverside fortress watches over the border bridge where cars and heavy vehicles drive across the river from Russia to the EU, and vice versa. Beyond the river, it is mirrored by Russia’s own Ivangorod Fortress: built in response to the Teutonic Order, a century later, by Tsar Ivan III. It was here, to a quiet corner in the courtyard of Hermann Castle, that Narva’s Lenin made his final journey—and it is perhaps not without a note of irony that the former Russian revolutionary will spend the rest of his days inside the high stone walls of a structure built to defend against Russian invasion.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

Located inside the main courtyard of Narva’s Hermann Castle (sometimes simply referred to as “Narva Castle”), itself administered by Narva Museum, access to the Lenin monument is dependent on the castle’s opening hours. The Lenin monument is neither an official nor permanent feature though, and so it’s always possible that some day it will be removed from public viewing altogether.

Published

October 3, 2019