About

As with clothing, museum curation endures trends that come and go. But unlike more traditional fashion, the consequences of styling in the art world can be drastically more permanent.

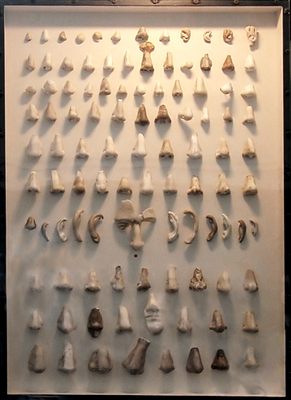

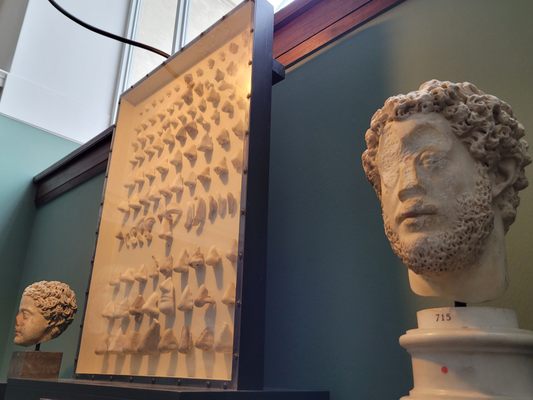

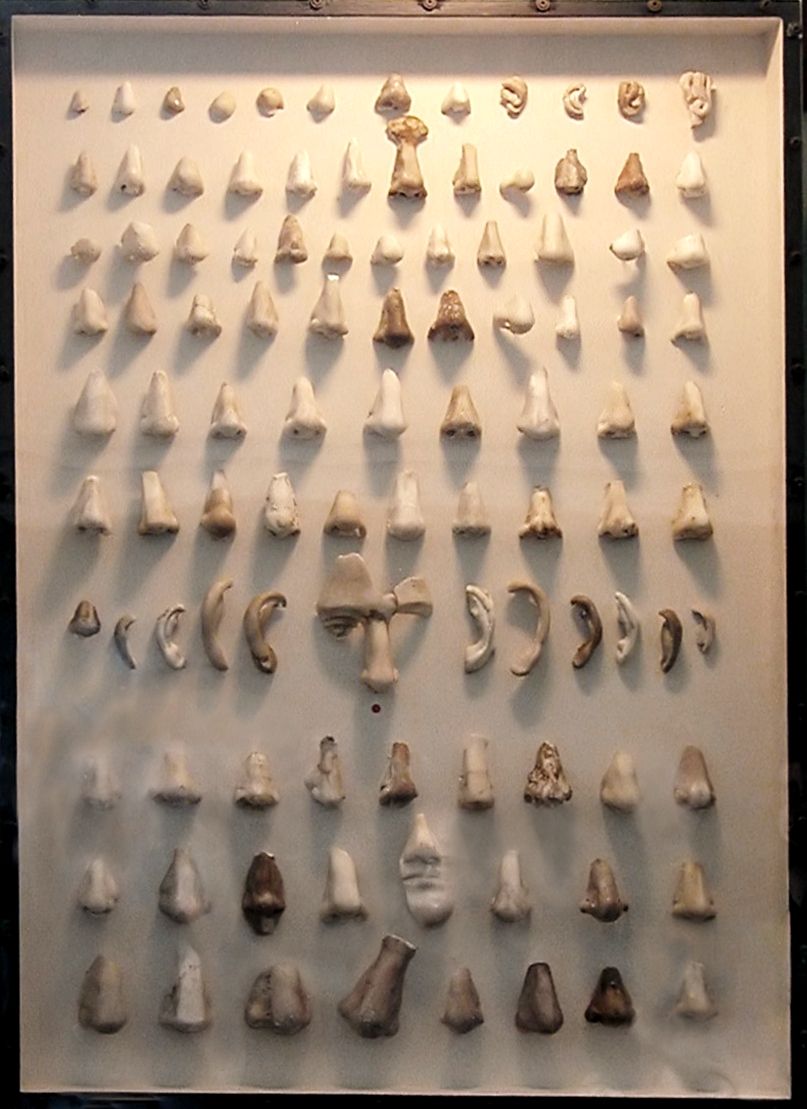

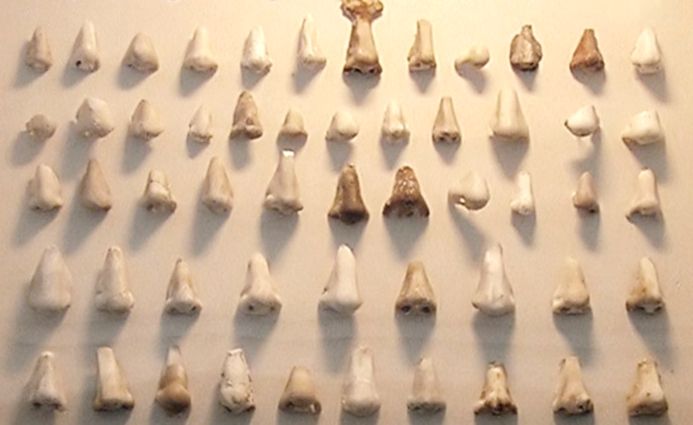

Hidden within Copenhagen’s Glyptotek art museum is a curious cabinet filled with 100 plaster noses. Visitors who find it stare in wonder as a single body part has been arranged so meticulously that it would appear to be its own work of art. In reality, they’ve come face to face with the Nasothek, a piece of commentary on the history of art preservation.

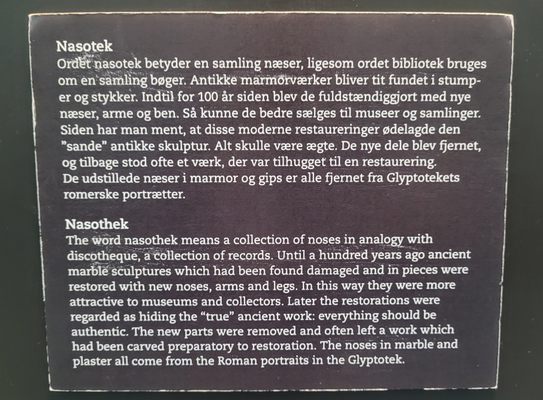

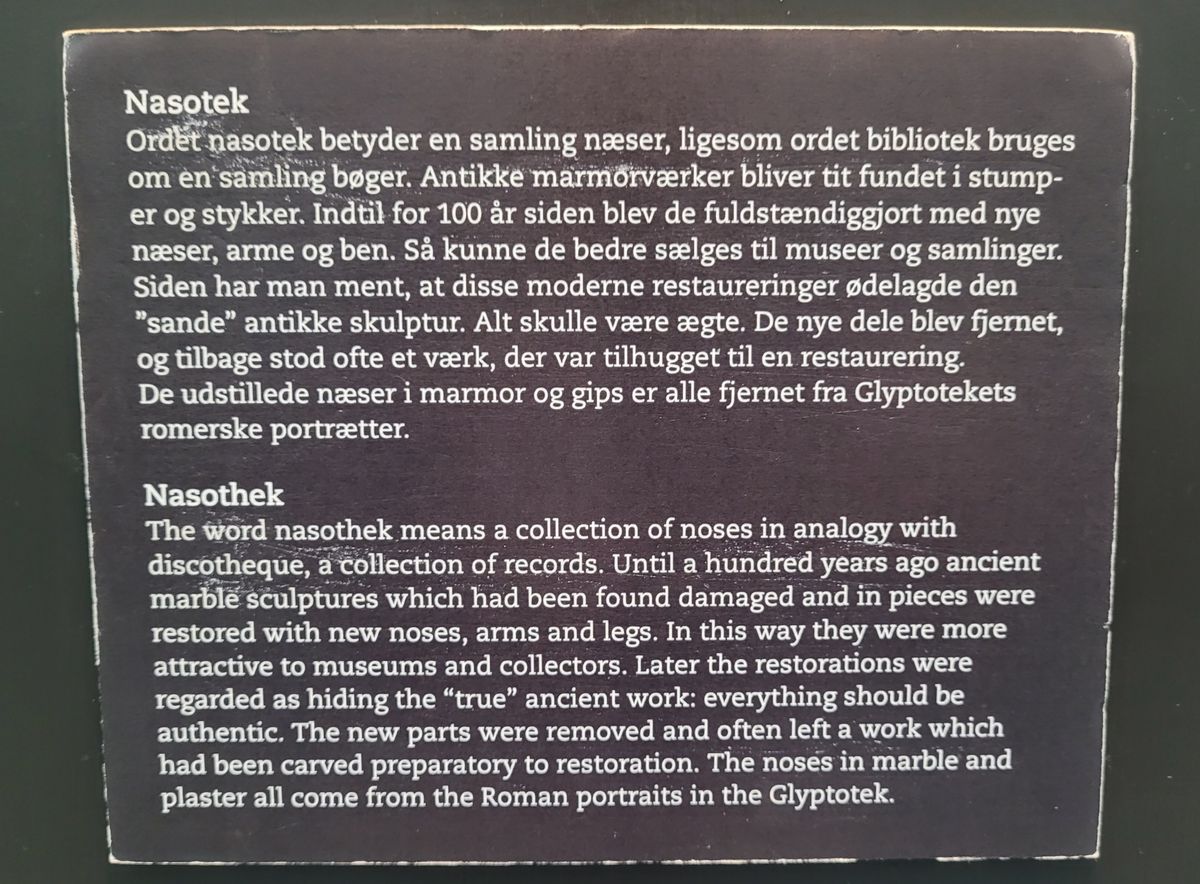

Known for its large body of Greek and Roman works of sculpture, the Glyptotek has witnessed its pieces break over the years. The most vulnerable place often fell on the statues’ noses. Particularly in the 19th century, it had been a common practice among conservators to apply a facsimiles of the broken element, so as to re-complete what had been lost.

Today this benign act of “restoration” reads like a grand faux pas. In the midst of an era of “de-restoration”, museum staff has taken to removing fake noses and appendages from sculptures to which they’d been affixed for decades.

Hands literally full of noses that once graced some of history's most prized countenances, curators were to decide what to do with the physical evidence of their ancestors’ art crimes. Rather than bury them, the Nasothek was born, which takes its name from the Latin for “nose” and Greek for “container.”

In exchange, observant museum-goers have been given a rare glimpse into the face of authenticity in the art world, tucked into the corner of a museum teeming with perfectly imperfect creations.

Related Tags

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

May 21, 2015