About

Fields of ironwork, piles of brick, and rows of stone slabs and ornaments, along with a research library stacked with books, patents, blueprints, and sketches make up the collection of the National Building Arts Center (NBAC), the largest collection of building arts in the United States. On a recent tour of the center, President of the Board of Directors Michael Allen described it as “one part memory palace and one part curio cabinet.”

Supplemented by thousands of artifacts donated by the Brooklyn Museum in New York City and other collectors, the majority of the collection is made up of architectural salvage obtained by the late founder Larry Giles. A former Marine and native of St. Louis, Giles garnered a love for the built environment from a young age. He was a self-taught student of architecture, surrounded by exemplary classical buildings made of the finest raw materials produced in St. Louis at renowned companies like the Hydraulic Press Brick Company and Winkle Terra Cotta Company. In the 1970s, after serving in Vietnam, Giles returned to his hometown to find that much of the architectural history he loved was disappearing.

New development projects were rapidly causing the demolition of historic buildings across the city. To preserve pieces of the past, Giles scaled iconic St. Louis buildings destined for the wrecking ball, salvaging anything he could, from ornamental stone and ironwork to structural steel and brick. He stored these pieces in an old carriage factory and started the St. Louis Architectural Art Company, selling artifacts to restorers who were renovating historic buildings.

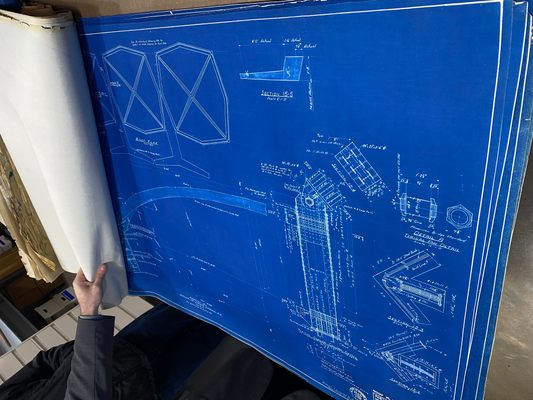

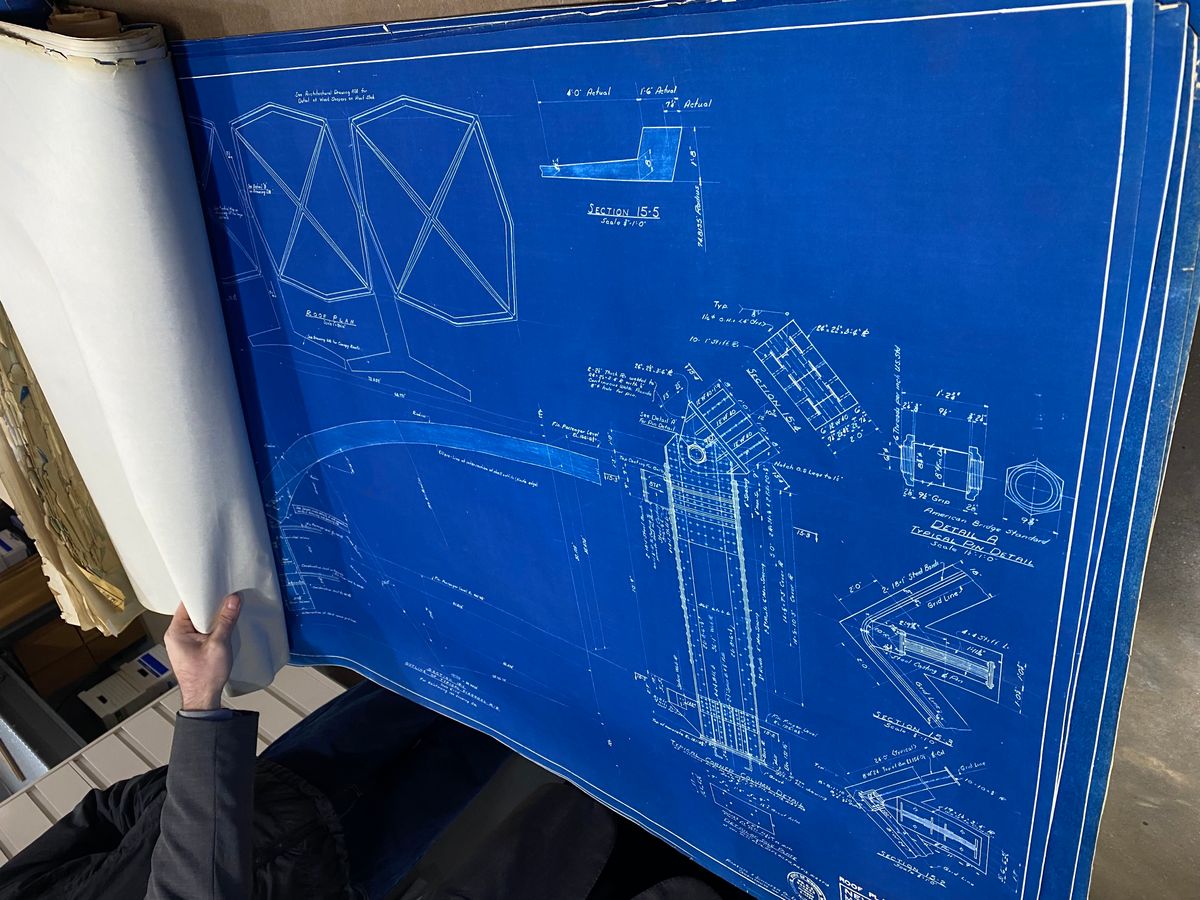

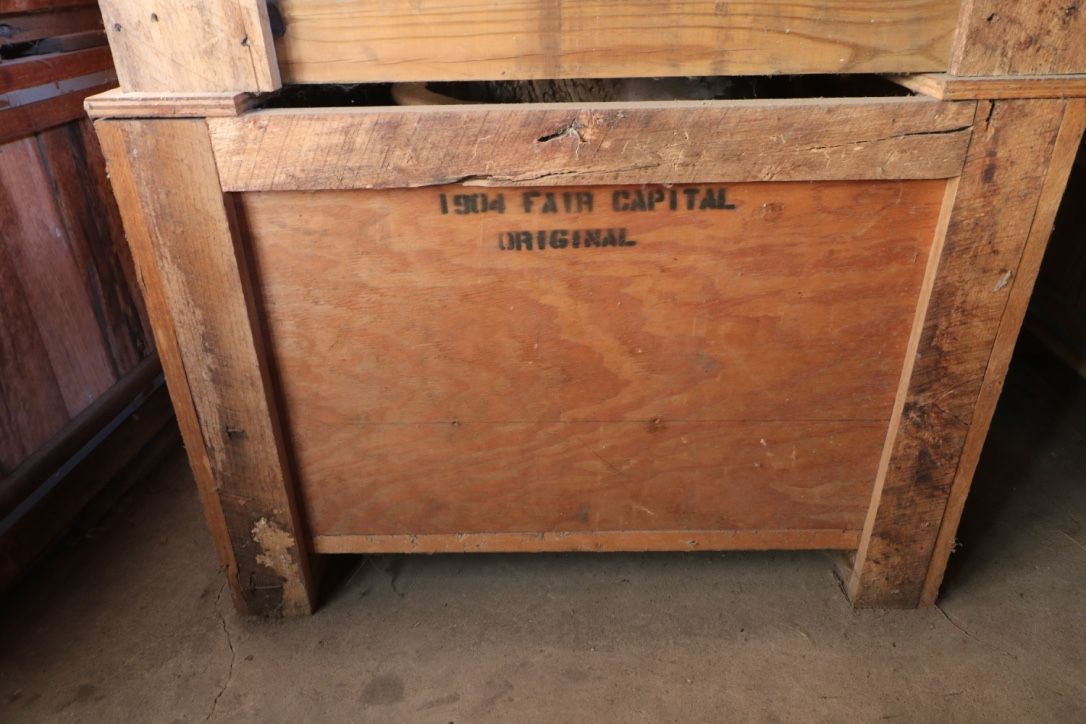

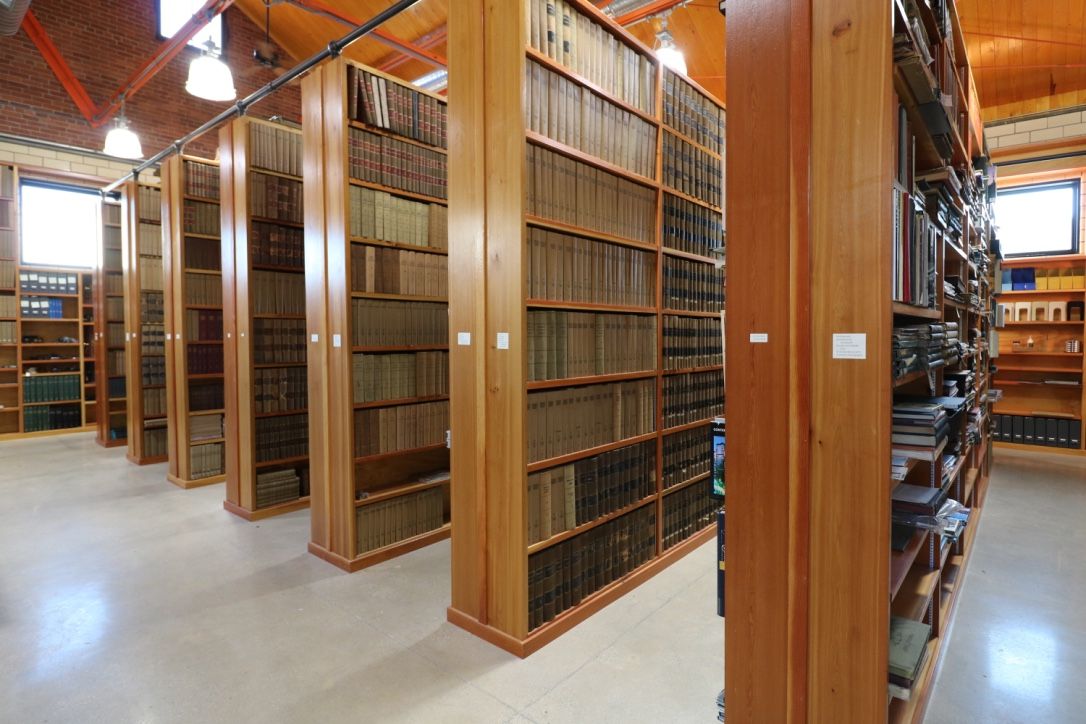

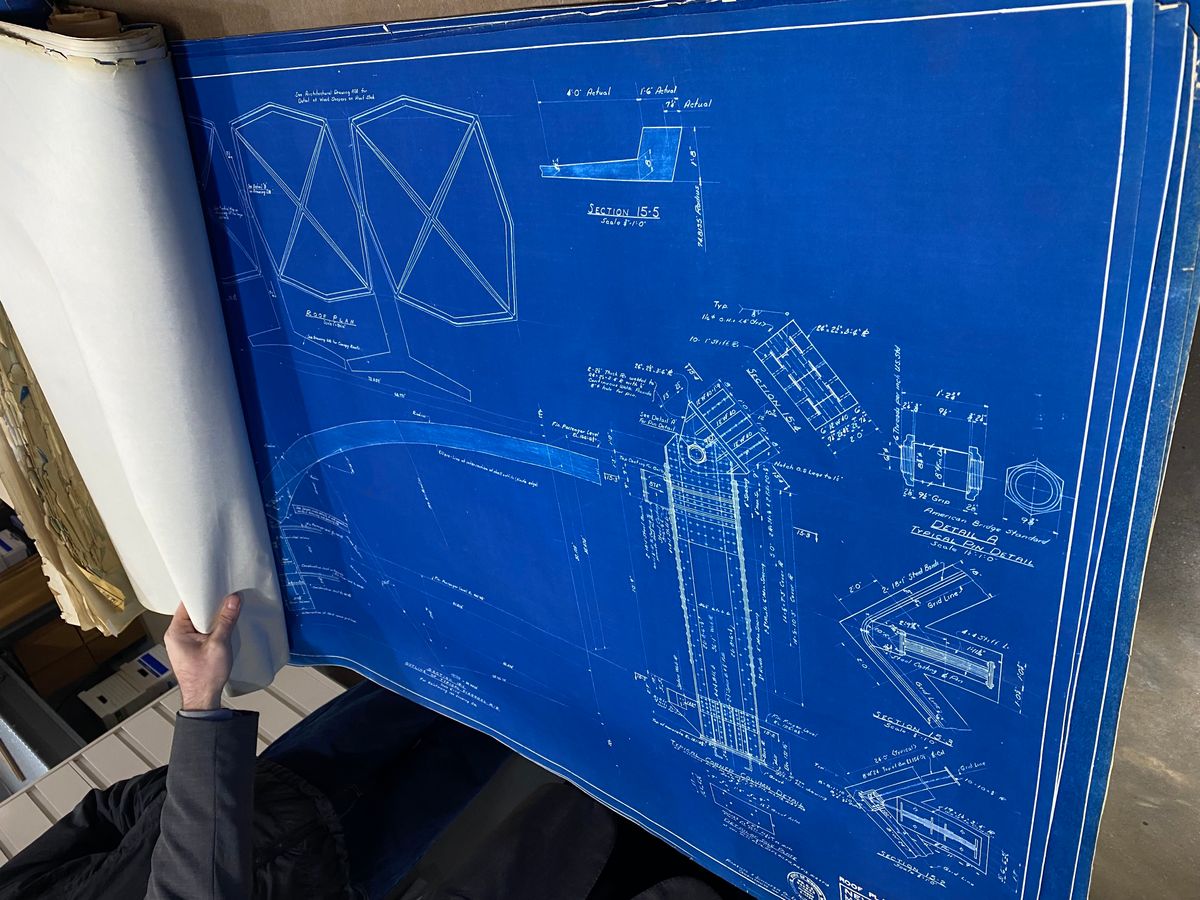

After closing the Architectural Art Company business, Giles turned his collection into a non-profit, and the National Building Arts Center was born. In 2005, his extensive collection moved to its current home, the former site of the Sterling Steel Casting Company in Sauget, Illinois, just across the Mississippi River from St. Louis. The fifteen-acre site, set in an industrial area nicknamed “the Pittsburgh of the West,” operated as a steel foundry from 1922 until 2001. Where you would once find early 20th-century laborers casting metal or making wood patterns, you'll now see towering stacks of wooden crates (which Giles constructed himself) and giant easel displays (also made by Larry Giles). Inside the extensive library, once the foundry’s employee shower room, there are rows and rows of books on engineering, extractive industries, construction, architecture, and automobiles (the last being a personal hobby of Giles'), not to mention the entire archives of the Hydraulic Brick Company, over 20,000 track maps from United Railways, and structural drawings from architect William Becker.

What lies inside the meticulously cataloged crates, on the easel displays, and in open fields behind the buildings are vestiges of lost buildings that tell stories of the evolution of building arts, from innovative technical achievements to changing tastes and cultural norms. There are Gothic spires and gargoyles stripped from a townhouse in New York City when they went out of fashion. Sitting in a field is a massive neon sign from the roof of the State Bank of Wellston, a rotating spectacle that, in its heyday, pilots used as a landmark when approaching Lambert Field. Steps away there is a stereotypical, though well-intentioned, sculpture of a Native American made by a local artist in the 1980s to serve as a symbol of Cherokee Street, recently removed to make way for a more culturally appropriate representation. In one of the buildings, there are ornamental pieces from a building demolished to make way for the Gateway Arch.

You can see examples of both hand-carved stone and mass-produced terracotta molds, signage, glass, building machinery (like elevators and electrical meters), lighting, structural steel, the odd toilet, and so much more. The collection is a comprehensive and invaluable resource for preservationists, scholars, students, and anyone who wants to learn about America's built past.

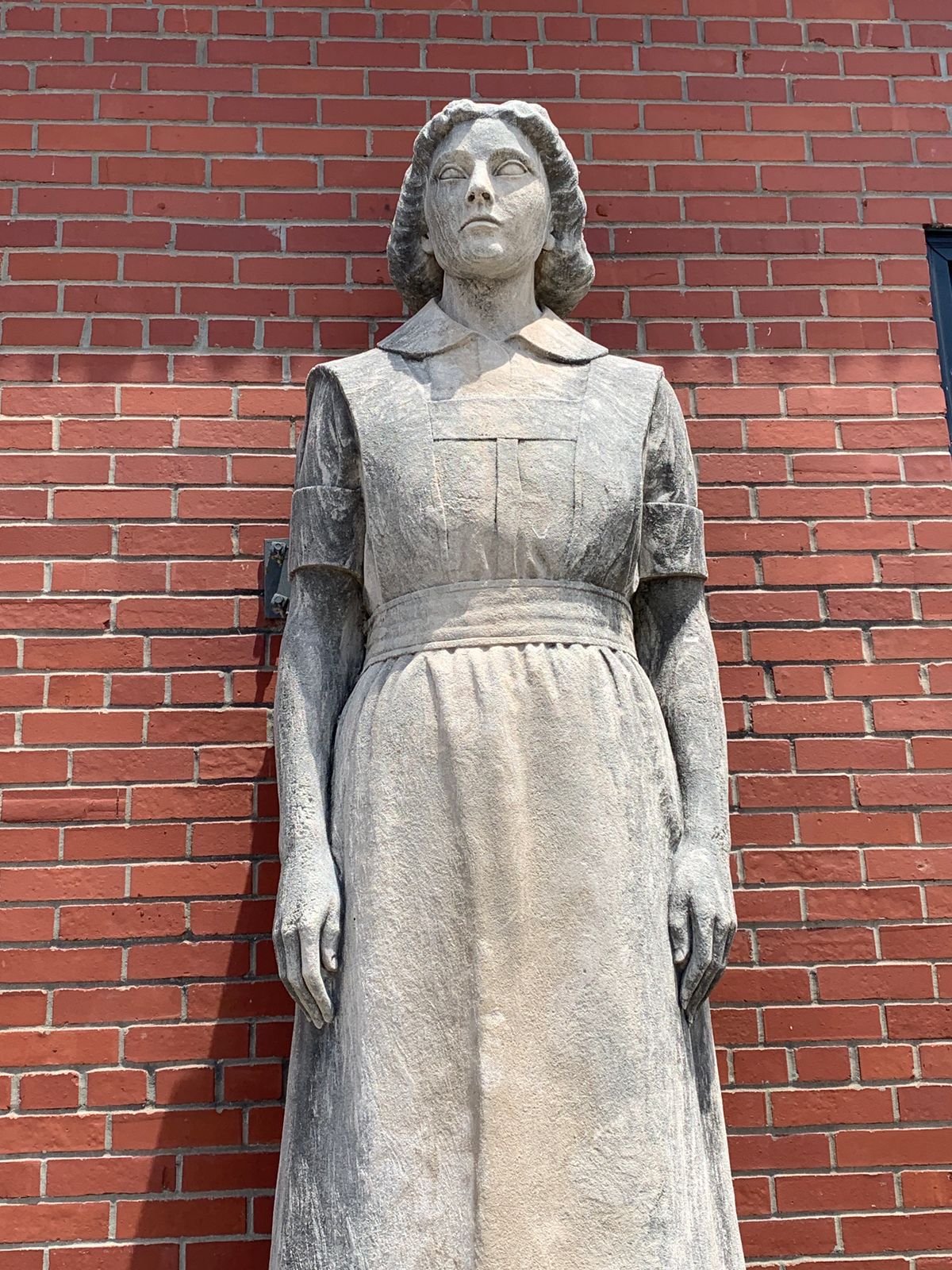

The National Building Arts Center is currently focusing fundraising efforts on bringing Little Liberty to the foundry site. Little Liberty is a thirty-foot replica of New York’s Statue of Liberty. Commissioned by auctioneer William H. Flattau, Little Liberty stood atop his Liberty Warehouse on West 64th Street from 1902 until 2001 when a developer converted the warehouse into apartments. Since then, the statue has stood in the sculpture garden of the Brooklyn Museum. Now, Little Liberty is set to head west. The NBAC has constructed a base that is the same shape and size as the original and an interior structure that will once again allow visitors to climb to the top. Visitors to the statue between 1902 and 1912 were treated to a bird’s eye view of Broadway, but visitors to Little Liberty soon will enjoy a view of the St. Louis skyline to the west, and to the east, a sweeping look at America’s architectural past.

In addition to being a fun new attraction, the statue will allow the NBAC to carry out its mission of “educating the public on all aspects of the building arts from design to fabrication.” Visitors to Little Liberty will be able to study traditional pressed-metal (repoussé) statuary and construction. There are big plans for the future of the National Building Arts Center, which aims to become “the nation’s finest museum collection and research center for the study of the built environment.” Much work has already been done to convert the historic steel foundry structures into a modern museum, and it's thrilling to watch the progress.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

You can visit the National Building Arts Center on a docent-led tour. More information can be found on the NBAC’s Eventbrite page for 2022 tour dates.

If you would like to support the Little Liberty project, or for more information, you may contact museum staff at staff@nationalbuildingarts.org. You can also support the NBAC by purchasing artifacts from their Ebay store.

Published

February 15, 2022