About

To truly understand the era and the land that the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum celebrates, one need only look at the Oklahoma Land Run of 1889 for context.

Preparations began well before dawn on April 22, 1889, in the frontier town of Purcell. By the time the sun rose, several thousand homesteaders — men, women, and children — had amassed on the banks of the Canadian River that separated Indian Territory from a swathe of US-government owned land known as Oklahoma. At other points on the border surrounding this area of land, over 50,000 had gathered for the same purpose. Only several meters of water separated them from 1,887,796 acres of unoccupied land, staked out into 160 acre plots and fresh for colonization by the first man who was able to claim it.

In Purcell, the bank was lined with prairie schooners, which had positioned themselves at every point along the river where it was possible to ford. Lieutenant Samuel E. Adair and members of the Fifth Cavalry patrolled the bank opposite, warily watching for anyone who tried to get a head start. Anyone who tried to make a move before noon was taken in an armed convoy back to Purcell.

By 11:40 am, those who had assembled on the banks before dawn checked their tack for the final time, as Lieutenant Adair stared calmly from the other side of the river. They were first in line to enter the "promised land," as it had come to be known in the East. It was a warm day in early spring, tempered somewhat by a southerly wind.

At noon, Lieutenant Adair looks at his watch, then motions to the soldier on his right. The soldier raises the bugle to his lips, sounds it once, and then steps back out of the way. The cries of thousands of homesteaders rise from the bank as the nervous tension swells and snaps. The first wagons plunge into the water, and the great Oklahoma Land Run of 1889 is underway. By the end of the day, over 11,000 lots would be claimed across the territory. Tent cities of up to 10,000 people would be established next to railway stations at Oklahoma City and Guthrie, where by midnight the towns’ boundaries and main thoroughfares were already staked out.

The Oklahoma Land Run was the first of five land runs into unoccupied territory in Oklahoma over the next 16 years. These were lands that had been ceded to the state by Creek and Seminole Native American tribes following the Civil War, and by 1889 were considered some of the most desired real estate left in the West. The events that occurred here on April 22nd embody in many ways the dangerous and pioneering nature of frontier life, which is commemorated at the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City.

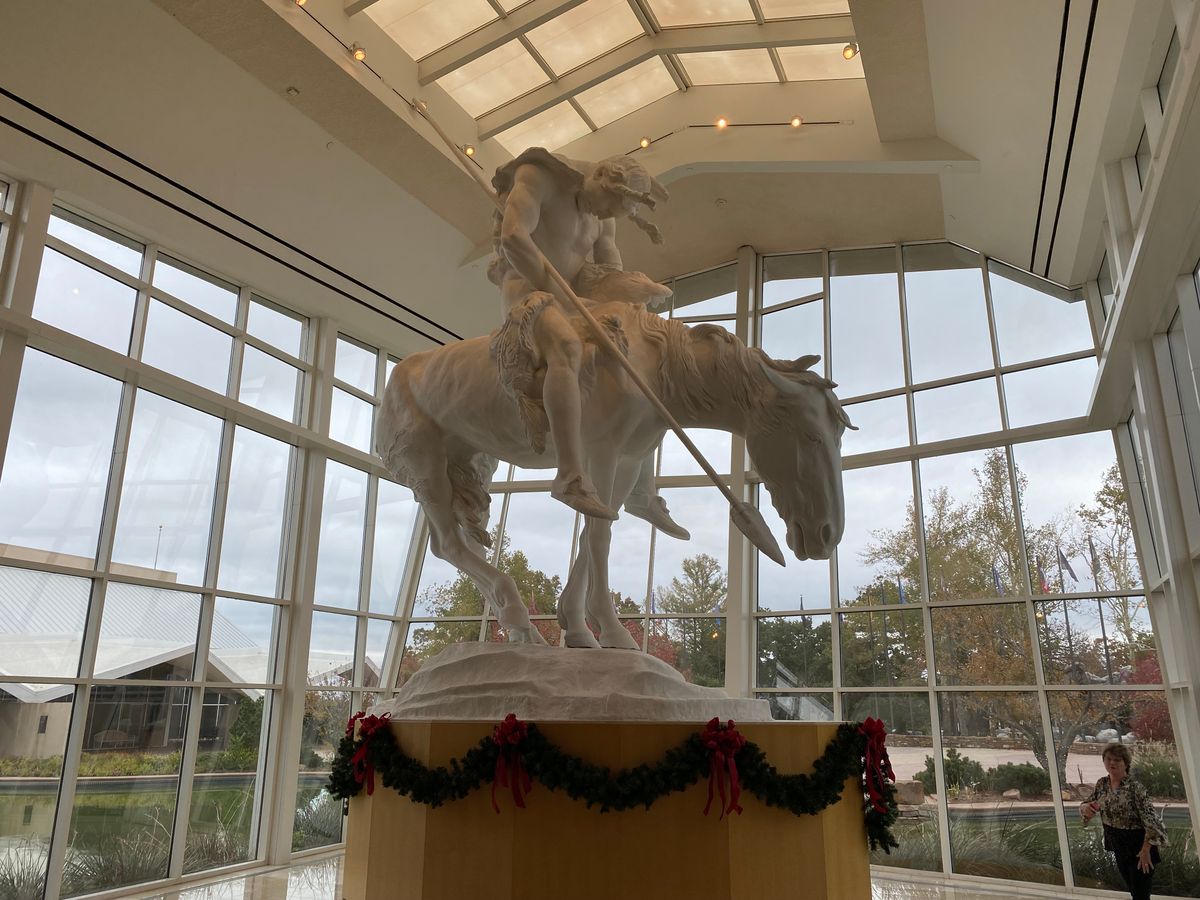

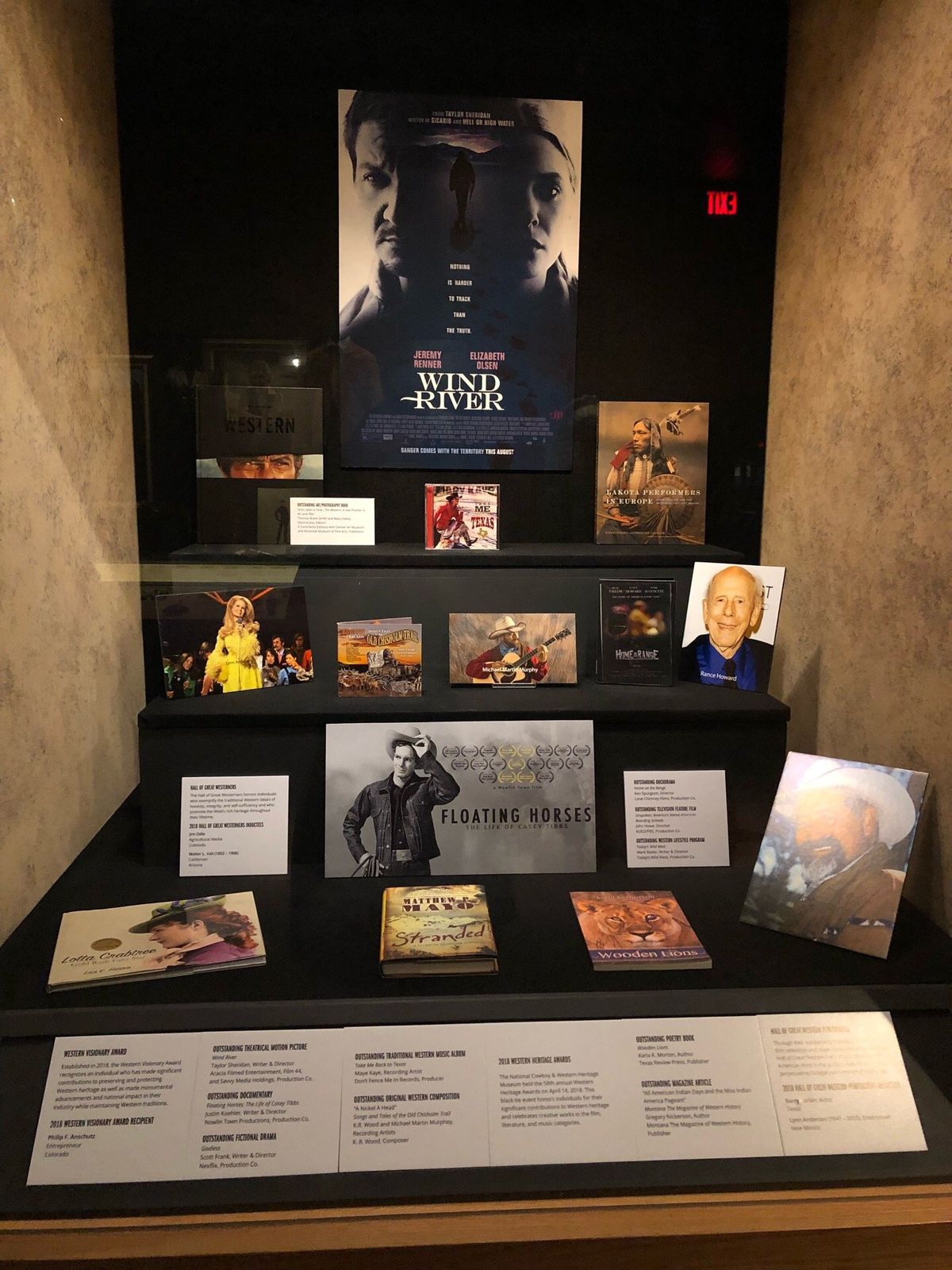

The museum itself was opened in 1955 and sits on Persimmon Hill in north-east Oklahoma City, overlooking the expansive lands that were settled here in 1889. Dominating the entrance foyer to the museum is perhaps one of the most impressive works housed in the museum, and indeed, one of the most recognizable of Western art: James Earle Frazer’s "End of the Trail," cast in plaster and standing at 18 feet high. The rest of the museum follows nobly from this impressive introduction, with a wide range of stylishly laid-out exhibits.

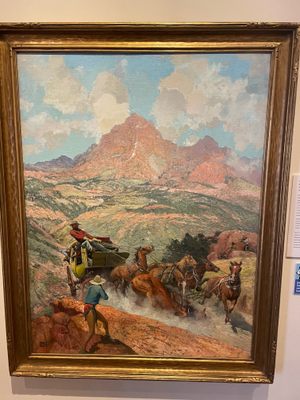

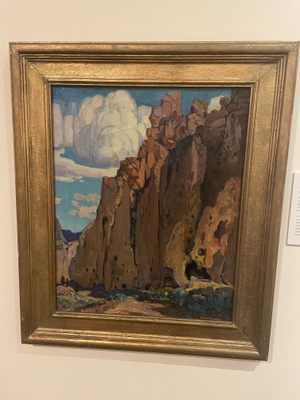

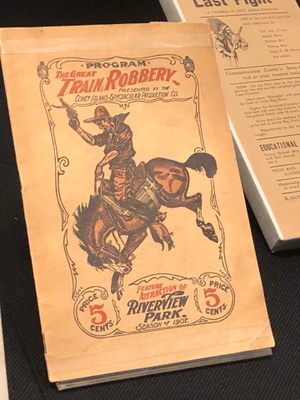

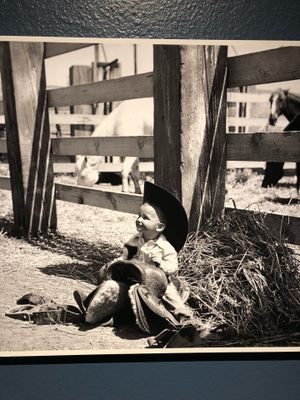

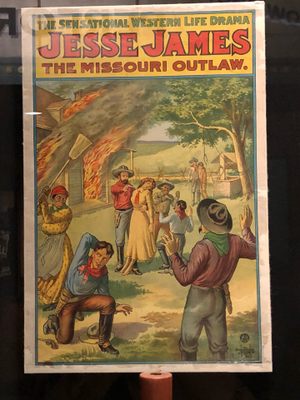

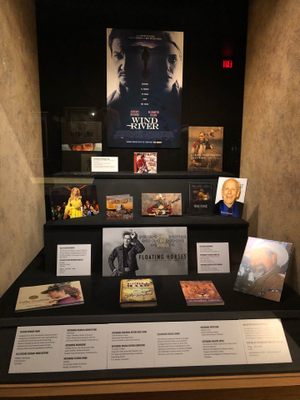

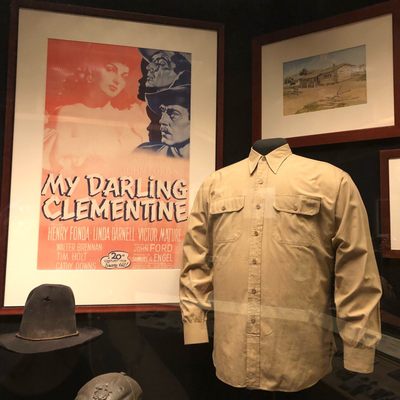

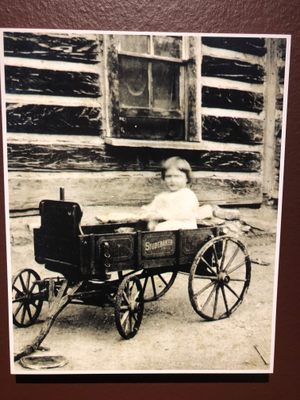

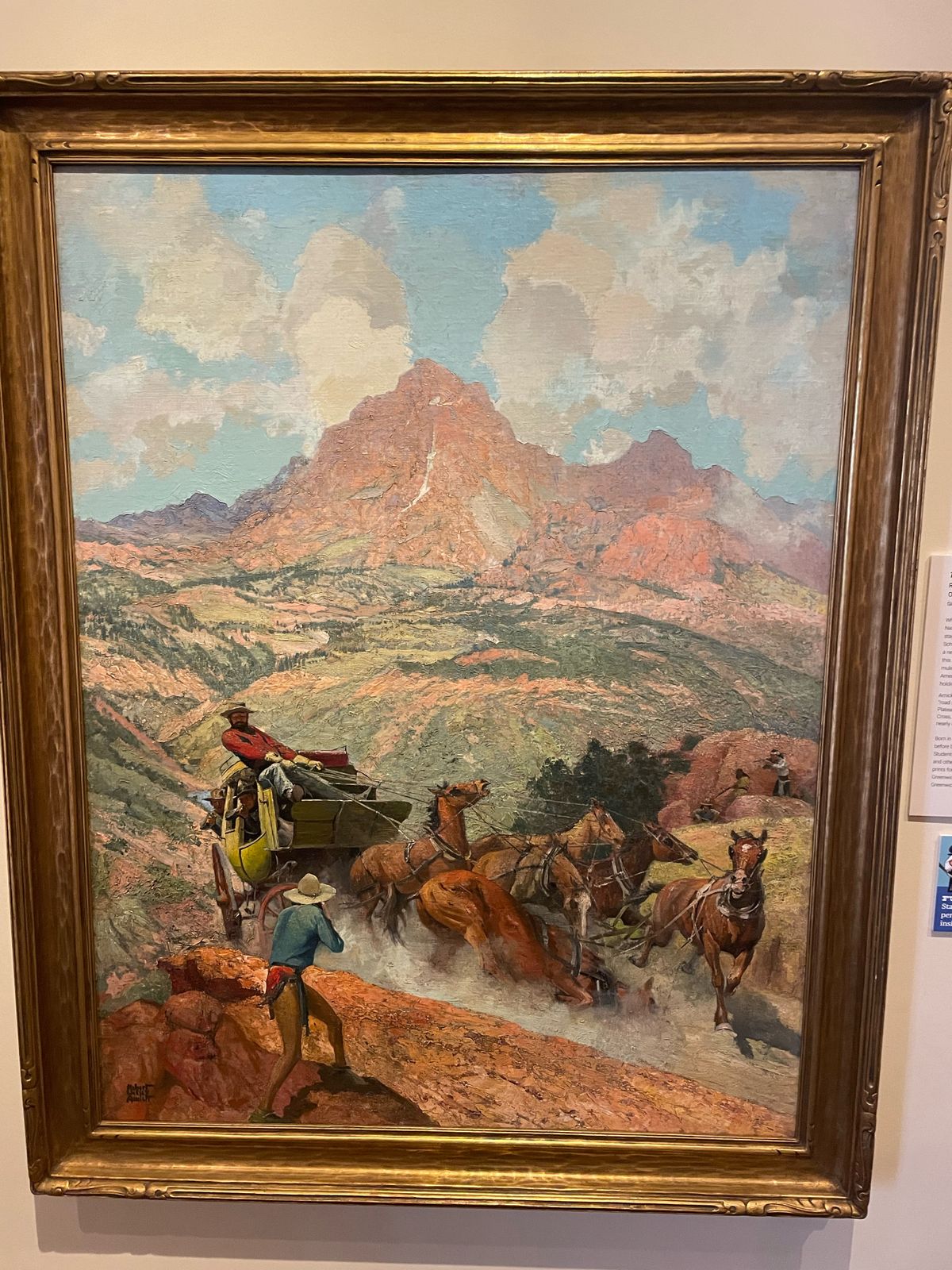

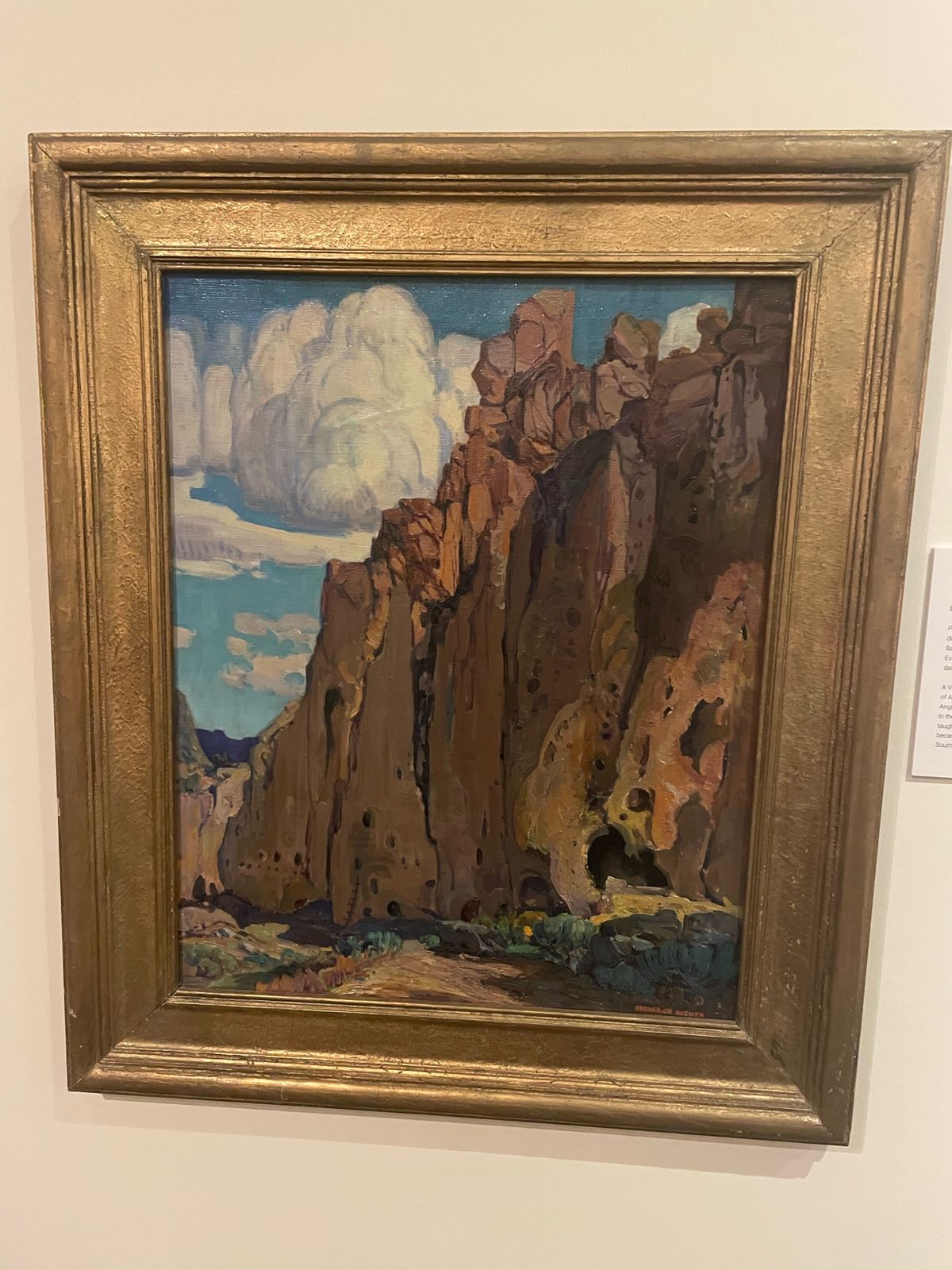

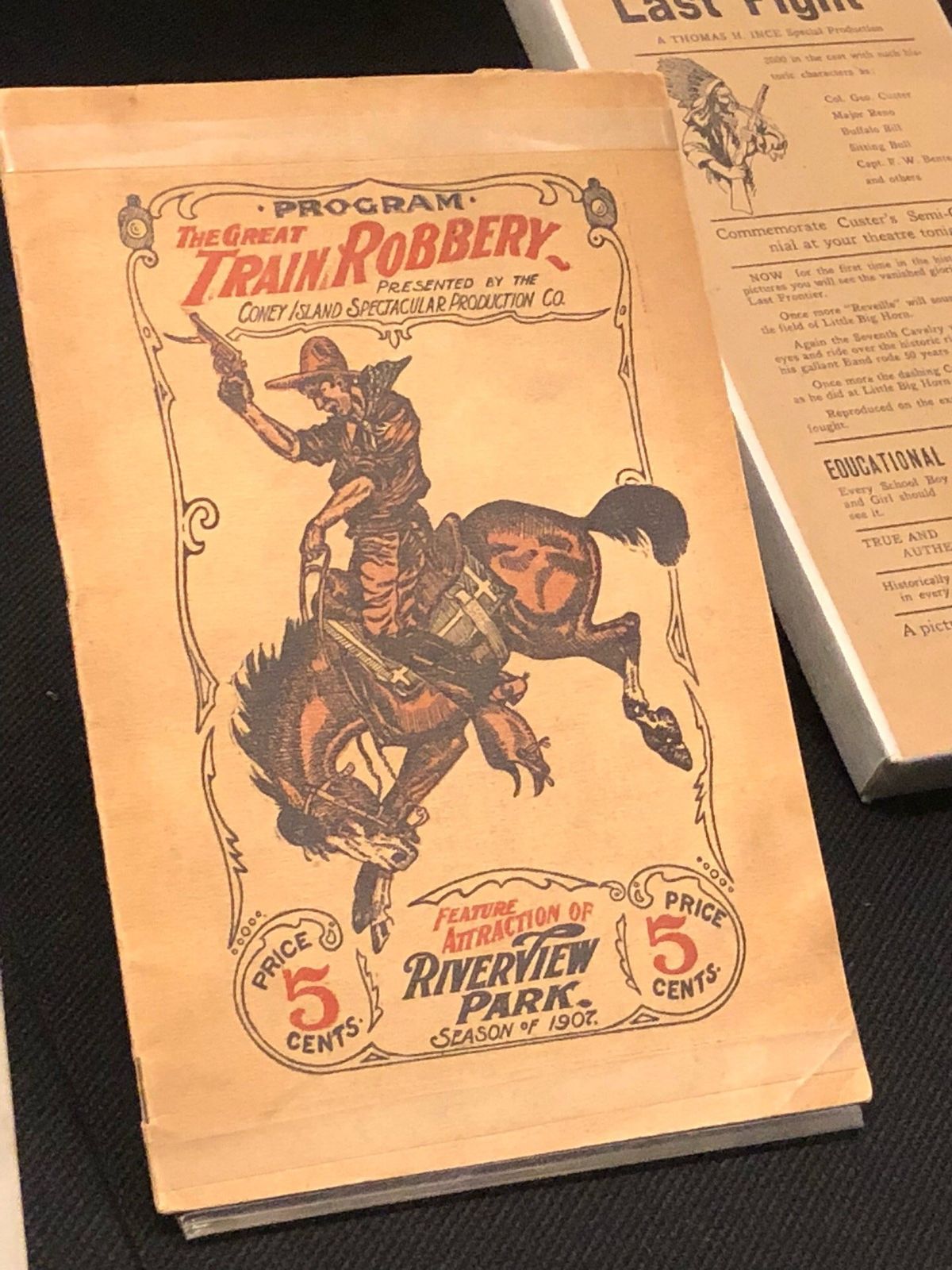

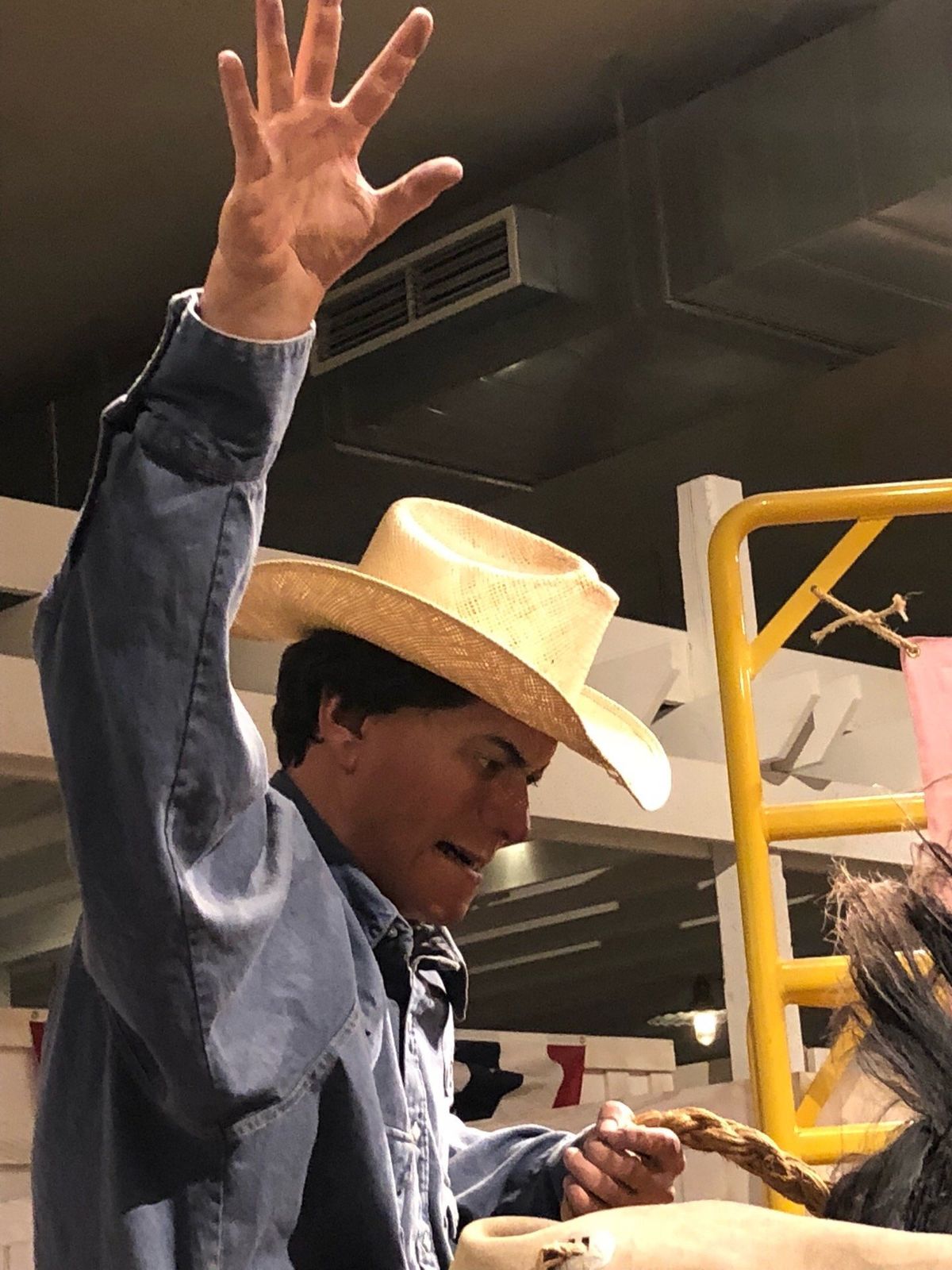

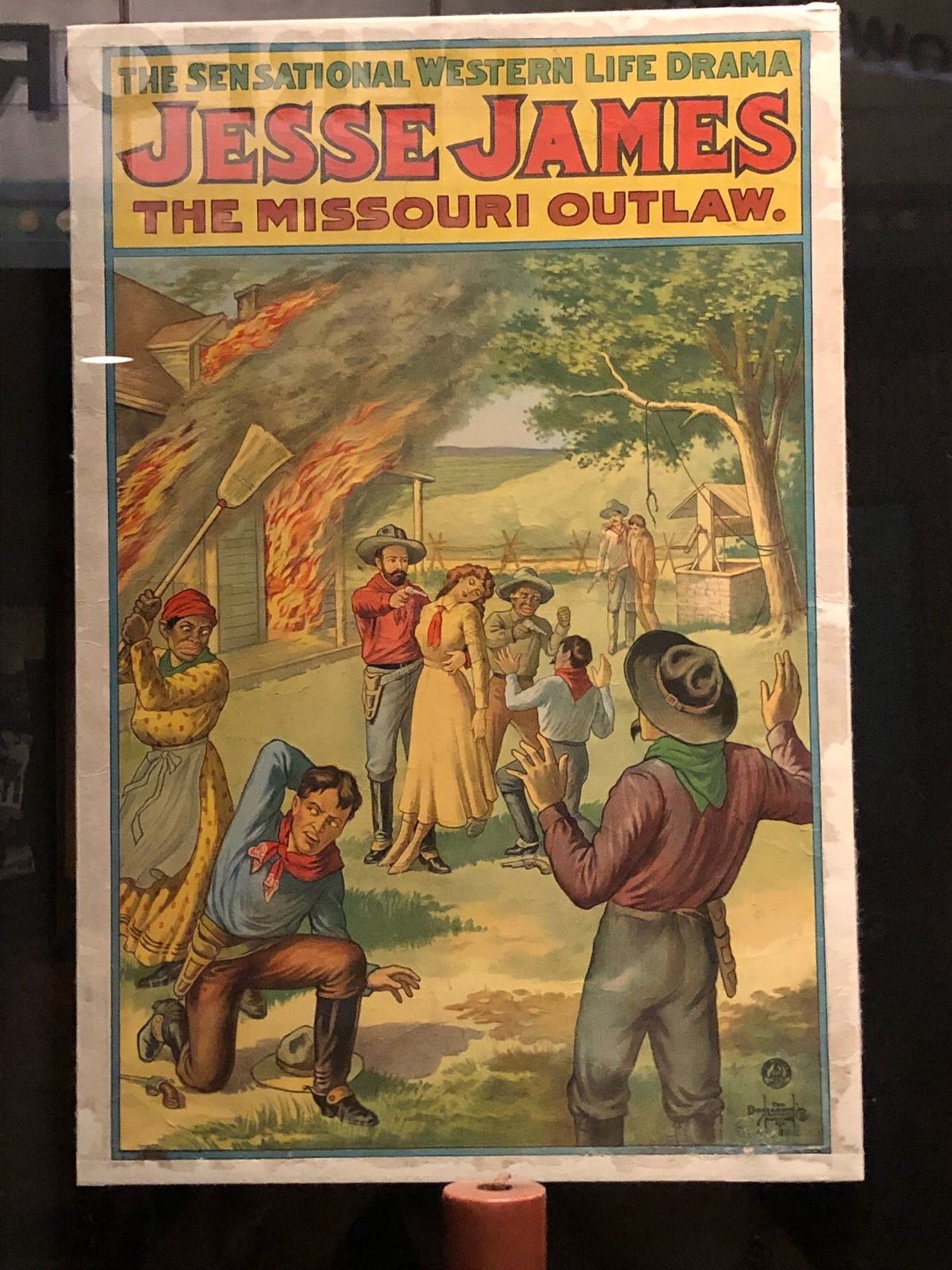

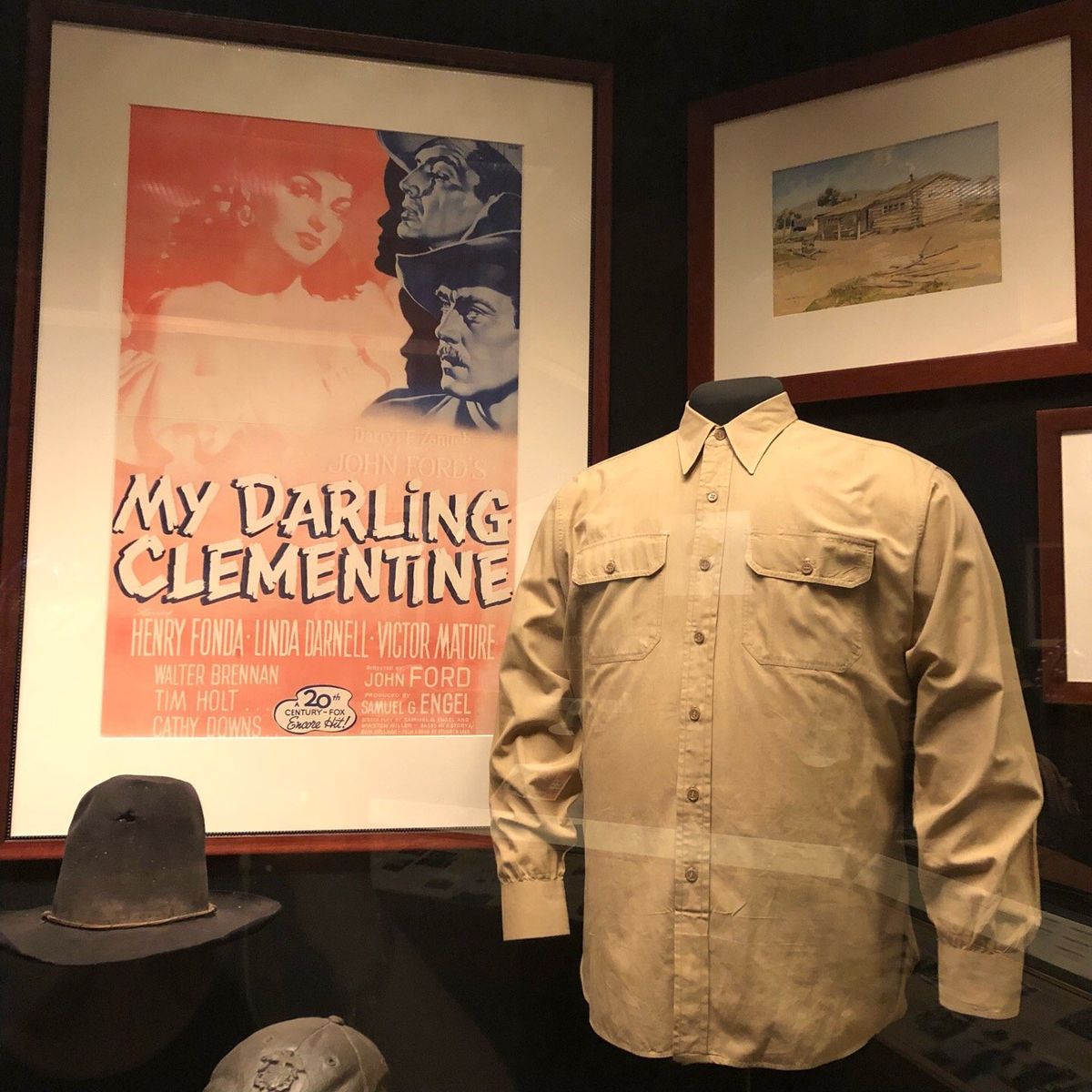

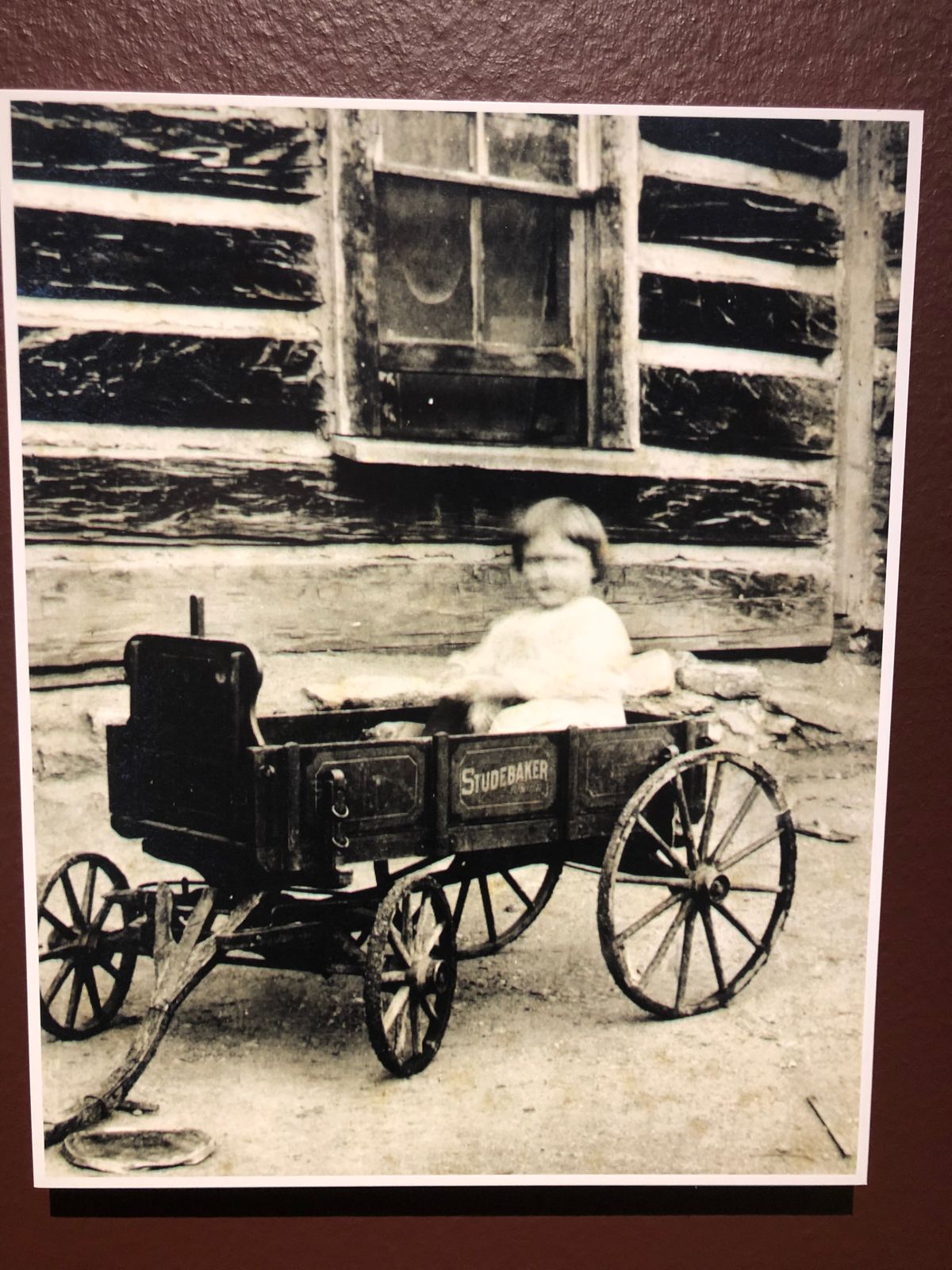

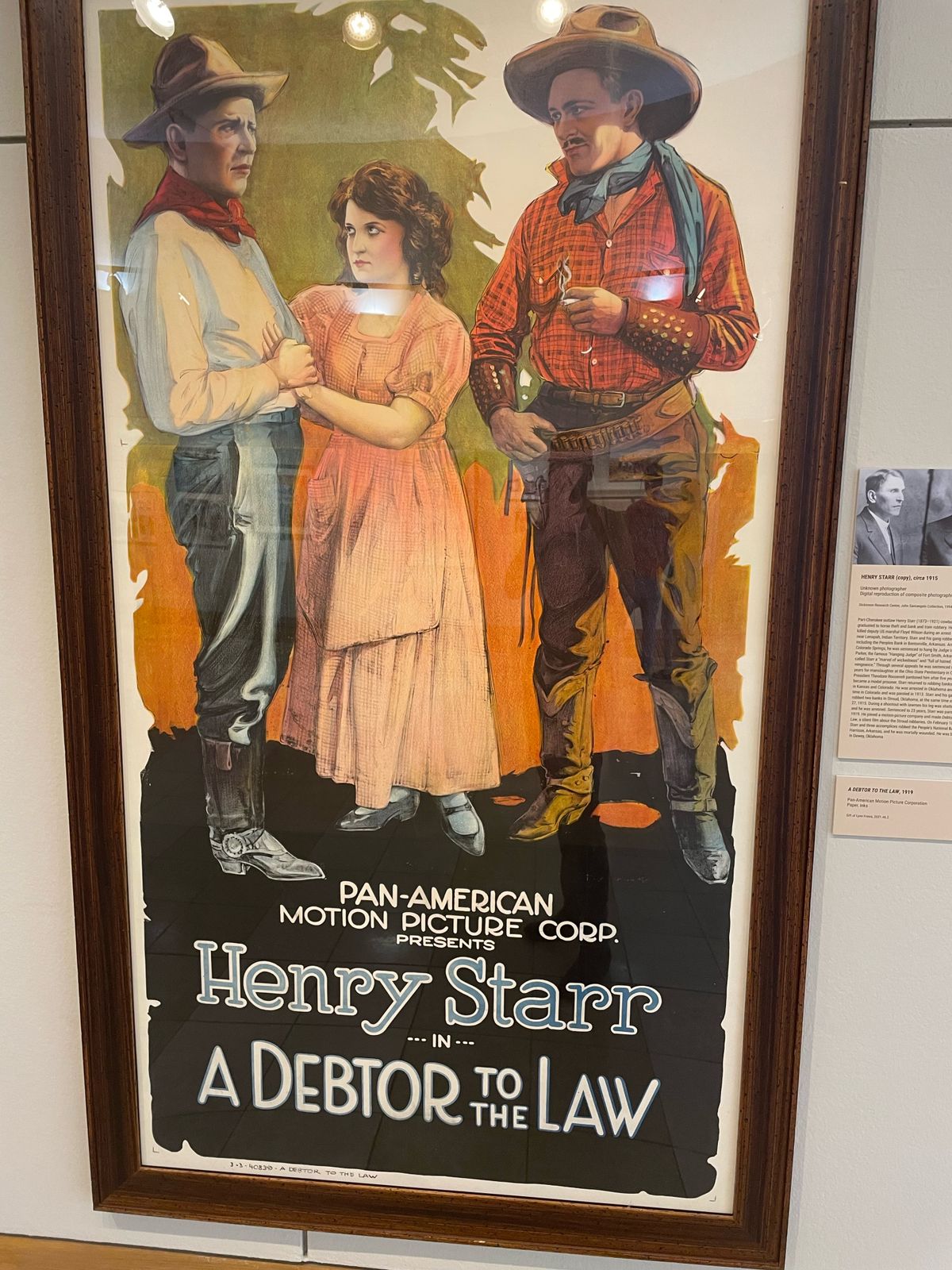

The site contains several galleries, including Art of the American West, which displays select paintings and sculptures from the museum’s 2,000 plus collection, including painters such as Charles M. Russell, Albert Bierstadt, and William R. Leigh, as well as sculptures by artists such as Gerald Balcair. Many of these paintings represent, naturally, a romanticized image of the Wild West, but it is one that must have been at the forefront of people’s minds as they moved their livelihoods out here in the mid to late 19th century. Then there is the American Cowboy Gallery, with glass cases exhibiting thousands of objects that help to interpret the cowboy’s history through material culture such as saddles, weapons, and items of clothing. There are also full-scale dioramas of various Western scenes such as a bugle boy galloping across the plains, a seasoned hunter teaching a young man to shoot antelope, and a small cowboy camp with a pot of stew, attached to a trammel, boiling over an open fire. An invitation to a hanging even lurks in one of the displays.

Finally, there is Prosperity Junction, a replica turn-of-the-century cattle town, built in the west wing of the museum. At the entrance to the Prosperity Junction gallery, an information plaque states that the replica town is located “somewhere in the west,” but it does not take much imagination to see the early years of Oklahoma City itself, after the Land Run of 1889, when the town was at the frontier of the promised land. In 2020 this area was expanded with an outdoor interactive children’s exhibit called “Liichokoshkomo” (“Let’s Play” in Chickasaw), which celebrates the tribal cultures of the west.

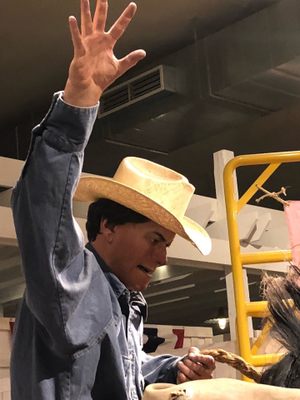

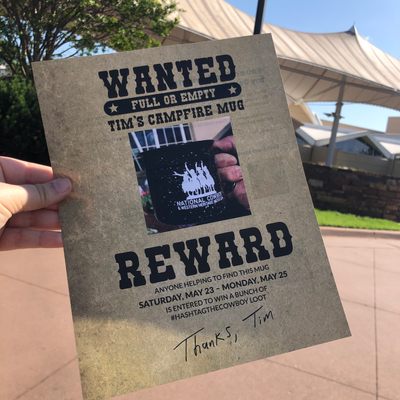

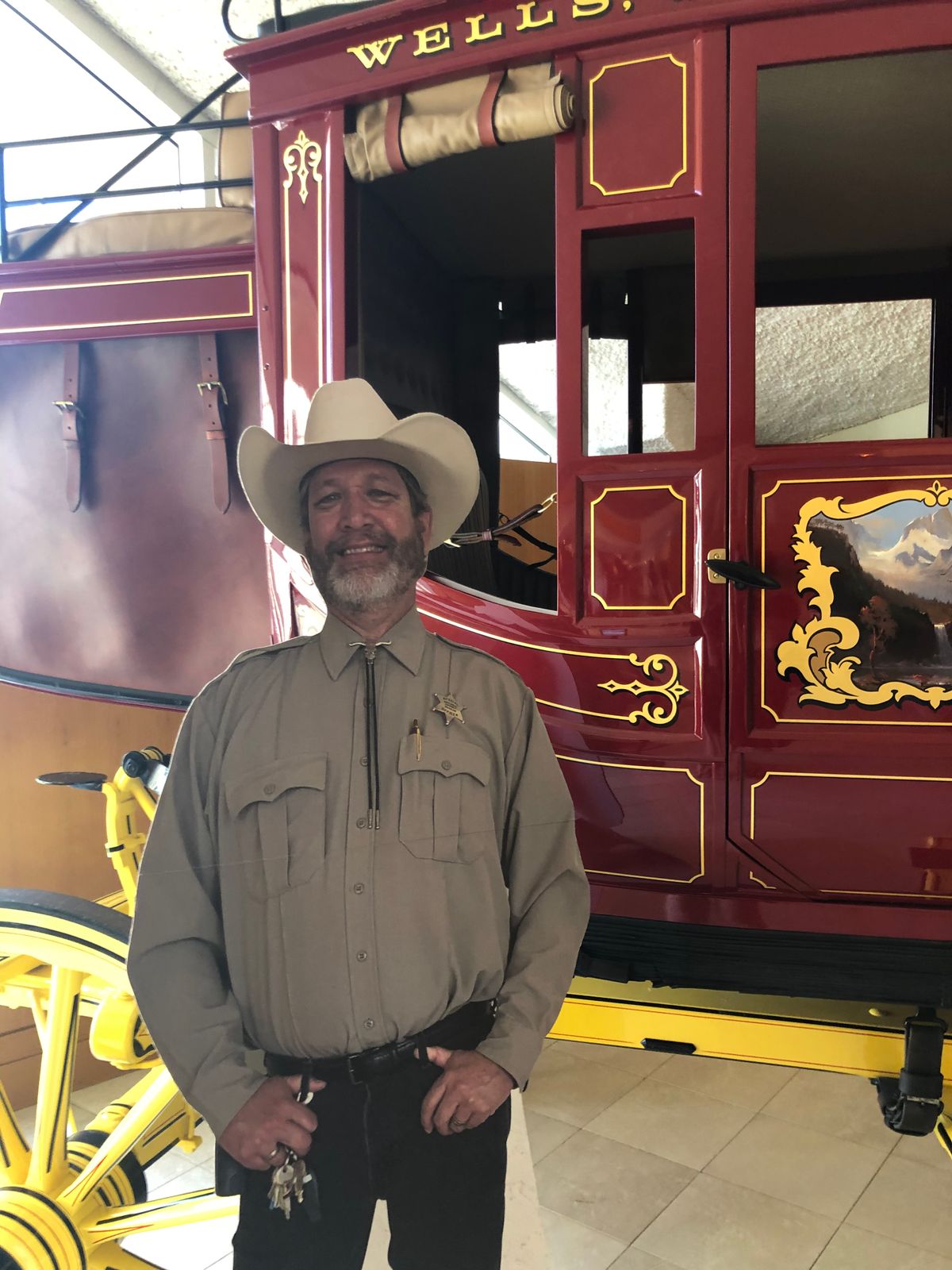

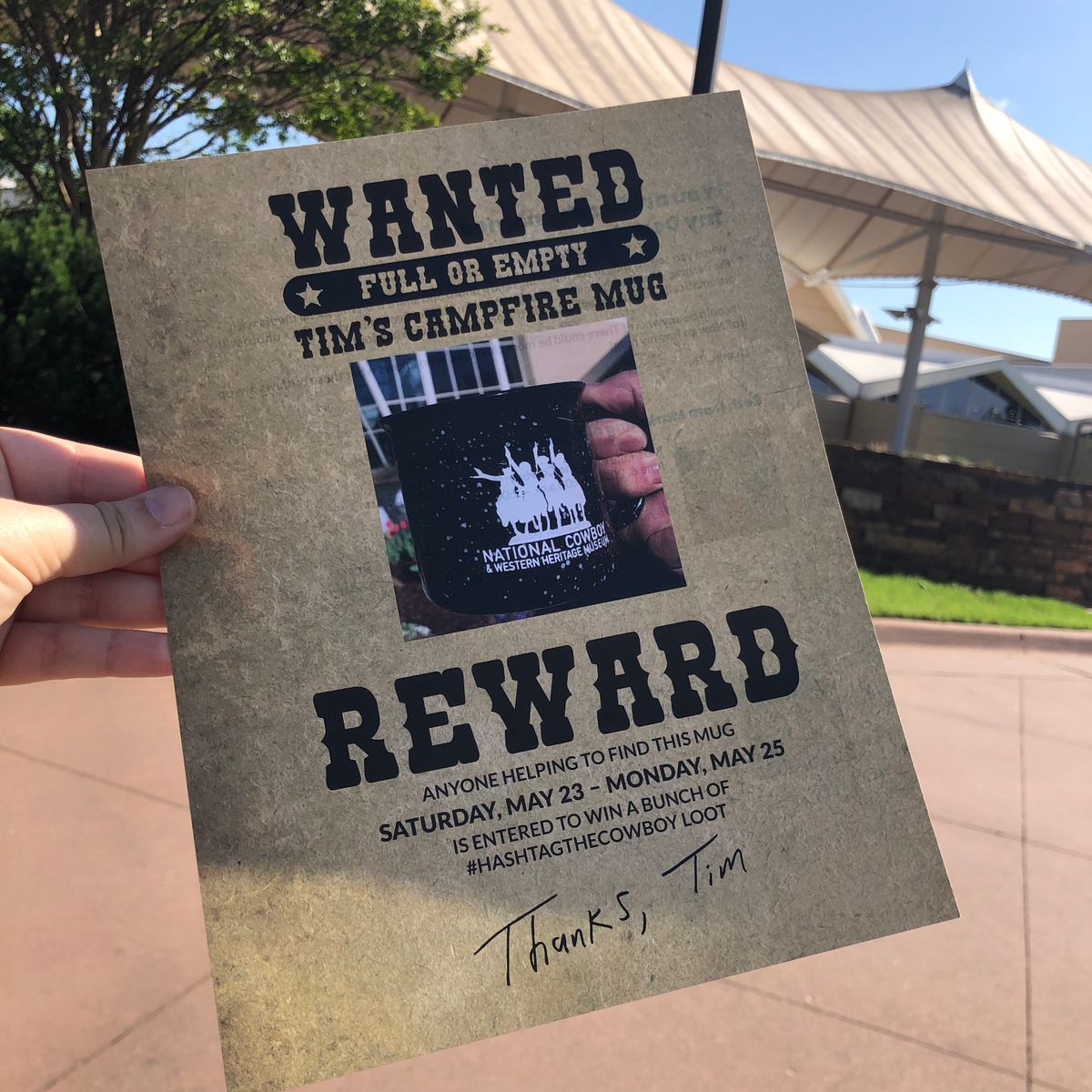

Behind the museum in its garden is also an easily overlooked gem: a graveyard for rodeo animals. In 2020, the museum made national headlines as its Head of Security (Tim Tiller) took over all social media accounts and captured America’s hearts with wholesome witticisms and endearing ineptitudes.

Related Tags

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

October 3, 2014