About

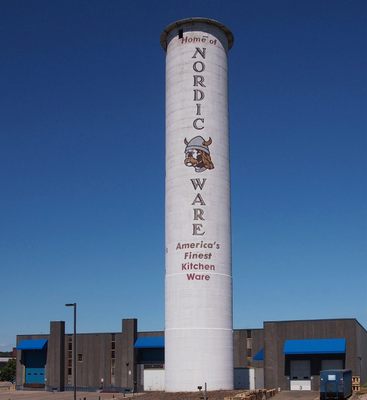

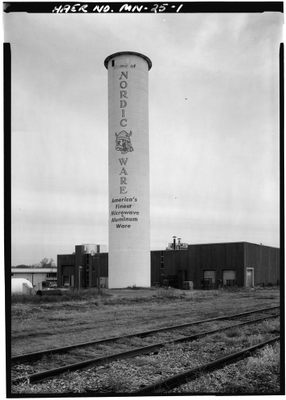

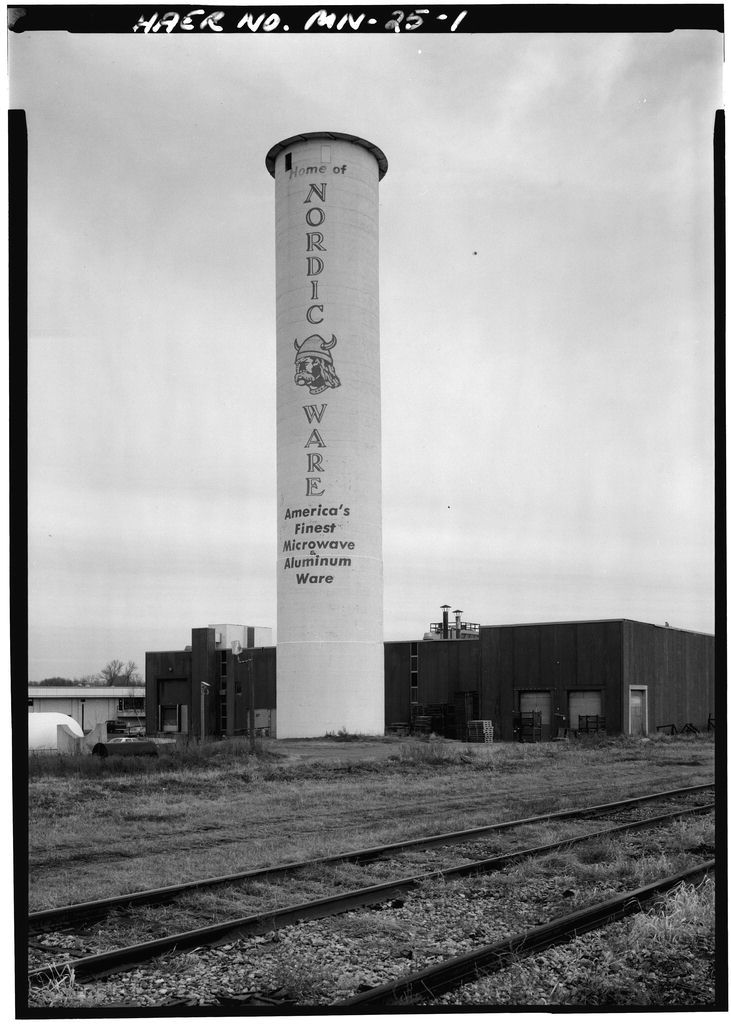

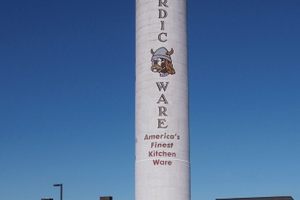

Perhaps the most unusual and notable source of inspiration for European architects was the lowly grain elevator. These hulking structures and their unique features caught the attention of European architects. Walter Gropius, a prominent figure in the International Style movement and founder of the Bauhaus, compared American industrial buildings, including grain elevators, to the “work of the ancient Egyptians” in their overwhelming monumentality. This concrete tower rising outside a kitchenware manufacturer in a Minnesota suburb may seem unremarkable at first glance, but it was the first of its kind in the country—and possibly the world.

The shortcomings of early grain elevators incentivized grain merchants to look for alternative construction methods and materials, which led Frank T. Peavey and Charles T. Haglin of Minneapolis, Minnesota, to create an innovative new grain elevator design that would influence decades of architectural design.

Peavey established F. H. Peavey and Company in 1874, at the age of 24. His customers frequently complained that their fields produced a surplus of wheat, more than local millers could use. Peavey recognized the opportunity before him: if crops could be shipped via train to cities, they could be sold to millers there. Peavey envisioned a series of collection points along the railways spanning America. He began buying grain outright from farmers until he filled a 16,000-bushel elevator. Then he began building additional elevators to store grain along the Southern Dakota Railway.

He struck a deal with Union Pacific to follow the railroad across the Wheat Belt, building 75 elevators and warehouses culminating with a 1 million-bushel terminal elevator at the Columbia River in Portland, Oregon.

In 1899, Peavey enlisted engineer and contractor Charles F. Haglin to develop new techniques for high-capacity grain storage. In the autumn of 1898, they built an experimental elevator in St. Louis Park, a suburb of Minneapolis, with a revolutionary “slip-form” technique in which the forms for the new concrete “slip” upward to rest upon the portion below as the wall hardened. Locals were skeptical and called the project "Peavey’s Folly."

The experimental elevator was filled with grain in a proof-of-concept test to demonstrate that the structure could hold and protect grain through the frigid Minnesota winter. Local grain experts predicted this lone column would burst like a balloon as the grain was drawn out at the bottom, and the widespread speculation drew a crowd of hundreds to watch as the grain doors were opened at the foot of the structure. Much to the surprise of skeptics, grain spilled out uneventfully; the contents were in perfect condition. Peavey’s Folly was deemed a success.

In 1908, Minneapolis-based photographer Edmund A. Brush took a photo of one of Charles Haglin's grain elevators. This grainy, black-and-white shot would make its way into the hands of European architects.

In 1911, Brush’s photo was featured in a lecture by a talented young architect named Walter Gropius. He was interested in the design of industrial buildings, including grain elevators from North and South America. His lecture focused on what he referred to as the "new monumental style." In 1919, Le Corbusier was working on an article for the magazine L’Esprit Nouveau. He wrote to Walter Gropius asking to use the grain elevator illustrations. A year later, one of Gropius’s illustrations appeared in an article by Erich Mendelsohn. They became established icons of modernity and architectural integrity.

Virtually all articles, books, and peer-reviewed papers on the International Style (a.k.a. Modern Architecture) include a discussion of American industrial architecture. Many such texts focus on the grain elevators of North America, touching on reinforced concrete as the material that makes their monumental presence possible. But few trace back to the lonely monolith in St. Louis Park. This seldom-mentioned contribution to the International Style deserves more credit than it’s given. Indeed, few who pass this tower are even aware of what purpose it once served—many believe it’s a smokestack used in the production of Nordic Ware, as it’s labeled today.

Related Tags

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

November 10, 2023

Sources

- Le Corbusier, R., Towards a New Architecture, 1923, Dover Architecture, Dover Publications, pp. 18.

- Gropius, W., The Development of Modern Industrial Architecture, 1934

- Heffelfinger, F. T., Fogerty, J. E., Oral History Interview with Frank T. Heffelfinger, 1983, pp. xi–xii

- General Leavitt Jubilant Over Railroad and Industrial Projects, The Portland Daily Press, November 19, 1898, pp. 10

- Peavey, F. H., Letter to John G. Massie, 1899

- National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form, February 4, 1971, pp. 49

- Schwartz, F. J., The Werkbund. Design Theory and Mass Culture Before the First World War, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1996, pp. 18–26.

- Moreno, C. M., The “Corporeality” of the Image in Walter Gropius’ Monumentale Kunst und Industriebau Lecture, Intermediality, Issue 24–25, Automne 2014, Printemps 2015

- Venturi, R., Scott-Brown, D., Izenour, S., Leaving Las Vegas, 1972, pp. 92–93.

- Banham, R., A Concrete Atlantis: U.S. Industrial Building and European Modren Architecture 1900–1925, 1986, MIT Press, pp. 11–15.

- Banham, R., A Concrete Atlantis: U.S. Industrial Building and European Modren Architecture 1900–1925, 1986, MIT Press, pp. 215–216.

- https://www.americanlandmarks.org/post/peavey-haglin-experimental-concrete-grain-elevator