About

Since the days of the Roman empire, alum was used as a mordant or fixative that allowed textiles to be colored using vegetable dyes. The manufacturing of alum was largely controlled by a Papal monopoly, and after the Reformation in England, the supply was interrupted. This forced the process of dying textiles to be outsourced.

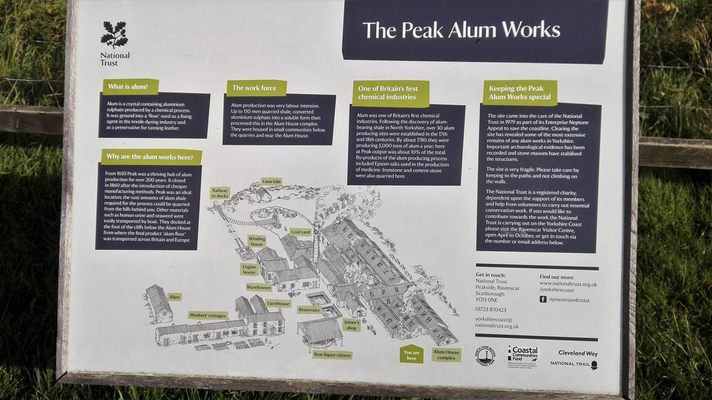

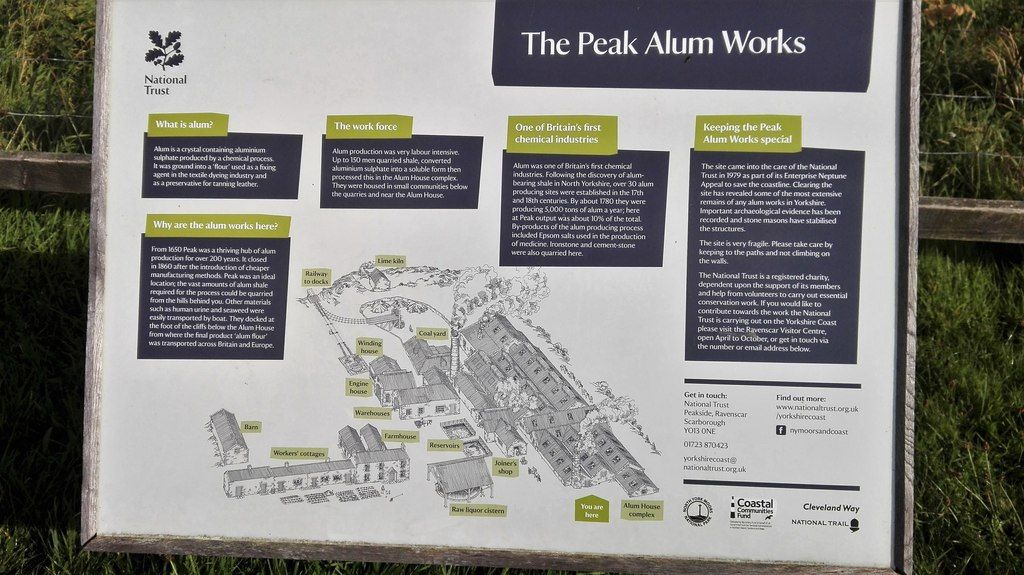

Alum was made, in part, from extracting shale, then burning mounds of it for up to nine months. During the 16th century, Thomas Challone found that fossils in shale along the Yorkshire coast were the same as those found in alum producing areas of Italy. An alum producing industry was thus established in the region.

The process of creating alum involved mixing leachate with aged human urine to provide ammonium, and roasted kelp for potassium. Massive amounts of urine were required, and public urinals were specifically established in Hull for alum production.

It was said that barrels of urine also came from as far away as Newcastle by boat and were hauled up the cliff by a tramway. It's estimated that some 200 tons of urine was used per year at the height of the alum industry. The tramway was also used to lower barrels of alum down to the boats.

This site at Ravenscar is one of the best-preserved remnants of this once important industry. It began to slowly lose steam around the mid 19th century when synthetic alum became available. When aniline dyes were invented a few years later, the mordant was no longer required. The last alum works in the region closed around 1871.

The site is under the protection of the National Trust.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

Around the site are interesting information boards that explain the ruins and the process of creating alum.

Published

April 4, 2020