About

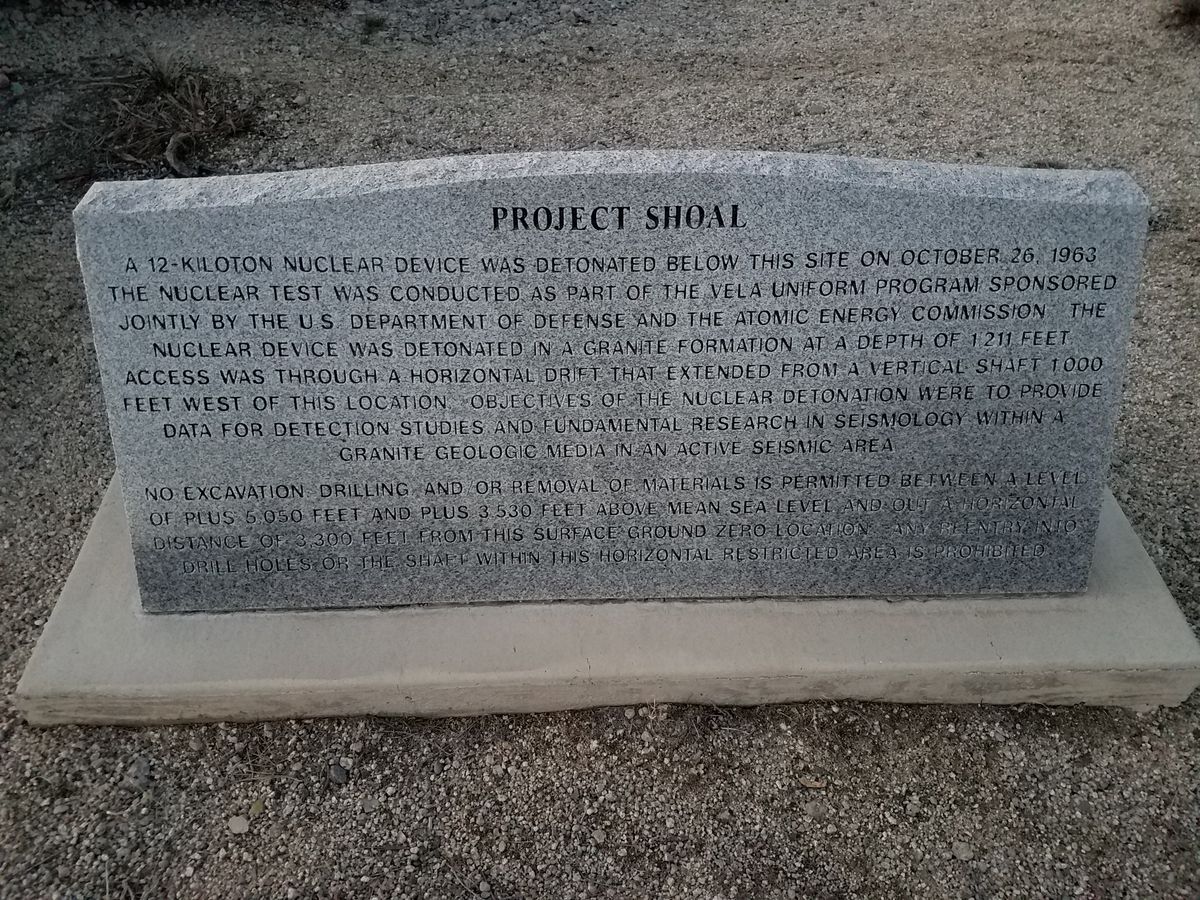

In the early 1960s atmospheric nuclear tests had been forbidden by the Limited Test Ban Treaty. But with the Cold War in full swing, the U.S. Government (and the Soviet government too, for that matter) felt they had to continue testing nuclear explosives, so the focus became testing underground. Nuclear detonations, especially those carried out underground, could be detected seismically and their yields estimated. This led to Project Shoal, which was located about 30 miles east of Fallon, Nevada.

There's a legend from the early days of nuclear testing that a shot carried out in extreme secrecy was immediately announced to the world by outside agencies. At first, security suspected a leak, but it turned out that it hadn't occurred to the brass that something as big as a nuclear explosion would generate an easily recognized seismic signal.

Yields were also capped by the Limited Test-Ban Treaty, so better estimates of them became critical to monitoring treaty compliance. (Both sides, of course, were convinced the other side was exceeding the limits.) Setting off nuclear explosions in different kinds of rock might allow better estimates of the yield by determining how much the seismic signal varied with the rock type.

At the site of Project Shoal, carried in the middle of the Sand Springs Range. The bedrock here is granite, which was in short supply on the Nevada Test Site, the usual site of underground tests.

The Project Shoal site is heavily monitored these days. Tritium (hydrogen-3), the radioactive isotope of hydrogen, is of particular interest because the hydrogen is bound up into water—and water contamination, of course, is of extreme importance in these arid lands. Tritium has a relatively short half-life (a little more than 12 years) and does not have a very energetic decay. But there's a lot of it.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

Go 31.9 miles east on US-50 from the intersection of US-50 and US-95 N in Fallon, Nevada to the junction of Nevada SR 839 (the "Scheelite Mine Rd"). Proceed 5 miles south to GZ ("ground zero"; "G2" on some maps due to a cartographer's misreading) road and turn right. It may not be marked; the junction is at 39.20194 N, 118.31354 W. The road is graded and should be passable to ordinary passenger cars in dry weather. Bear right at the junction 3 miles up GZ road; then bear left at the junction in another 0.7 miles. The turnoff to the stone monument is about another 0.2 miles.

The monument itself is about 250 feet up this access road. In contrast to many historic nuclear test sites, you can drive right up to the monument.

Published

June 30, 2021