About

Contained in Borneo's oldest museum is not only some rare historical taxidermy, but also an exhibit that remembers the historic (if barbaric) culture of headhunting.

In 1891, the second White Rajah of Sarawak, Charles Brooke began construction works on what would be the oldest museum in Borneo. This plan came after some nudging from his friend and famous British naturalist, Alfred Russel Wallace, who had been exploring the Malay Archipelago, collecting specimens for study at the time.

The Victorian period architecture, designed after a Normandy town hall, survived through the Japanese Occupation in Malaya (1941 – 1945) during World War II. It had the good fortune to fall under the protection of a Japanese officer, which is why the museum suffered very little damage and looting. A lucky thing too because the natural history collection housed in this museum is regarded as one of the finest in Southeast Asia, which dates back to the dynastic English monarchy of the Brooke family (1841 – 1946).

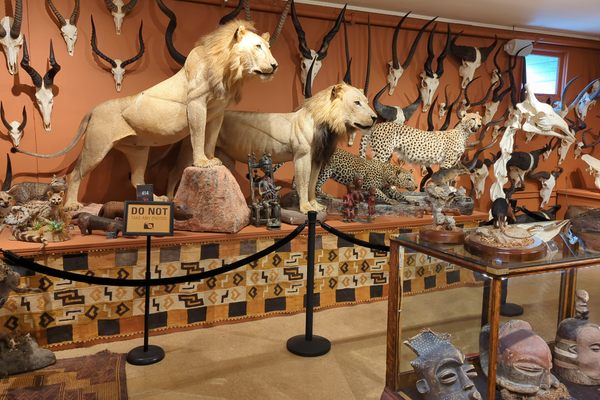

On the ground floor of the Sarawak Museum, you’ll find taxidermied exhibits frozen in time in their wood and glass display case, ever watchful of the many visitors who had walked through the Natural History gallery for decades. They had seen the world changed, although the exhibits themselves remained the same, if not somewhat disintegrating a little as time goes by.

A great deal of the collection comes from the Brooke Era, where the taxidermy procedures had been done not in Sarawak, but all the way in Britain. This preservation took place in the 1800s, so delivery by sea took about three months each way yet the fragile shipments remarkably managed to arrive at their destinations without harm.

Case in point would be the Orangutan exhibit. As the story goes, the first Rajah of Sarawak, James Brooke, shot two Orangutans during a hunt. He had both packed in ice, shipped to Britain to be taxidermied and mounted, and later shipped back to the Sarawak Museum. Today, this exhibit, along with others from that era have remained as they were in the Natural History gallery. This gallery is home to various taxidermied specimens including primates, avians, felines, and rodents found in Borneo.

The natural history collection is not the sole appeal of the Sarawak Museum however. The first floor features ethnographical artifacts of indigenous peoples of Sarawak, including a wide collection of traditional ceremonial masks from different tribal groups. Among the local culture, carved wooden masks are worn by the spirit doctors of a tribe and different masks serve different ritualistic purposes. They can be used to celebrate a good harvest or for spiritual ceremonies like exorcising evil spirits from a victim’s body. The museum’s collection contains mainly masks from the Iban, a tribal subgroup of the Dayak people of Sarawak. Ceremonial masks come with varied expressions, and some are even implanted with actual human hair as facial hair.

Also on the first floor is a model longhouse built to depict the traditional living spaces of the historic Dayak people. In previous eras, the Dayaks practiced headhunting, and human skulls would be preserved and installed in longhouses, believing that the trophies would bring a good harvest and fertility to the community. The replica community hut is adorned with its own human skulls. Of course, the practice of headhunting has long been eradicated since the days of the White Rajahs. No need to lose your head worrying over it when visiting Sarawak today.

However, maintenance of the heads is not to be taken lightly, even to this day, for as long as human skulls are present in a longhouse there are rules and rituals to follow. The heads need regular food offerings and a constant fire lit beneath them. Failure to do so would anger the spirits of the heads, and this only spells bad omens to the inhabitants of the longhouse. Just to be safe, don’t mess with the heads.

Update as of February 2020: The museum is closed for renovations, but there are plans for it to reopen sometime in 2020.

Related Tags

NEW - Wild Borneo: Secrets of an Ancient Rainforest

Orangutans, fishing villages & untouched beauty in the Borneo Rainforest.

Book NowPublished

June 9, 2013