About

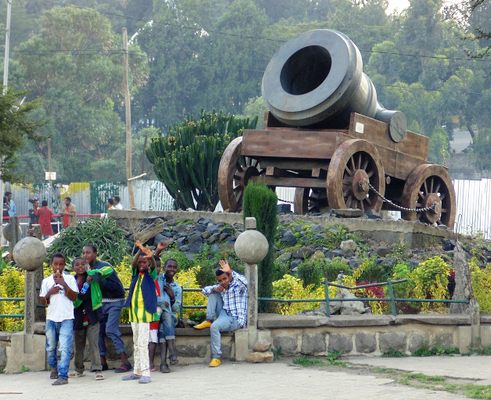

This replica of a giant mortar stands in the middle of an Ethiopian traffic circle. The weapon it commemorates was built by the Christian hostages of an Ethiopian emperor and was abandoned atop a hill, where it still lies today.

When the Ethiopian Emperor Tewodros II accepted Christian missionaries into his capital, it was not for their religious guidance. The Christian monarch was after their science, and more specifically, their help in building ever larger cannons and mortars.

In the mid-1850s, Emperor Tewodros II had a vision for a modern, industrialized Ethiopia. The Christian ruler dreamed of restoring a strong monarchy, ending the slave trade, and creating a modern military that would keep Ethiopia strong and safe. But to do this he would need the support of foreign powers, in particular, the British, and their knowledge of weaponry.

The British, however, were not as accommodating as Tewodros would have liked. The Emperor wrote a letter to Queen Victoria asking her to send skilled workers to teach his subjects how to produce firearms, but the letter was ignored.

Tewodros, therefore, turned to the European missionaries who had come to Ethiopia, seeking not their religious guidance but their scientific knowledge. At the time, he told his British confidant John Bell that “he would have been more pleased with a box of English gunpowder” than with their religious books.

So he commandeered the missionaries as his weapon makers, placing them all in a precarious position: they would try their best to produce cannons and mortars, or risk upsetting the monarch. None of them, however, had any direct knowledge of how to make weapons; at best they had some experience with casting metal.

A foundry was built at Gafat, and the missionaries managed to build a succession of mortars and cannons of dubious quality, with Tewodros demanding increasingly larger weapons. The pinnacle of all this trial-and-error cannon making was a seven-ton mortar that Tewodros named Sebastopol, after the site of a battle during the Crimean War.

Capable of firing half-ton artillery rounds—at least in theory—Sebastopol was the pride of the Ethiopian arsenal, which now numbered 15 cannon and seven mortars. Still, Tewodros was not happy with the standard of his weapons and sought further help from the British. But this was when things started going wrong for the modernizing Ethiopian monarch.

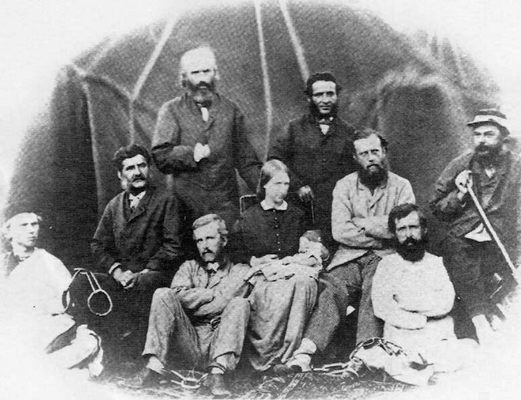

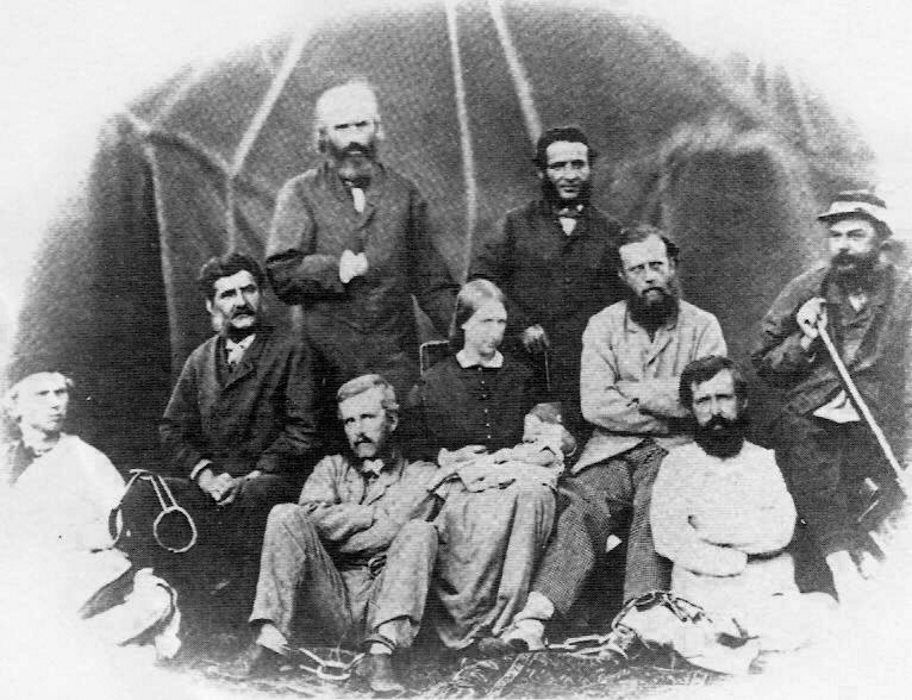

After two years of waiting, Tewodros was still hoping for a reply from Queen Victoria. But his patience was just about spent. Angered, he took hostage the British Consul in Ethiopia, Captain Charles Duncan Cameron, the very man who was supposed to personally deliver the letter into the hands of Victoria. He also imprisoned all the British subjects in Ethiopia, along with various other Europeans who happened to be passing through, in an attempt to get the Queen’s attention.

This was a very bad idea. On December 21, 1867, a British force was dispatched from Bombay. It included 13,000 troops supported by 8,000 auxiliary workers, thousands of mules, hundreds of camels, and 44 Indian elephants.

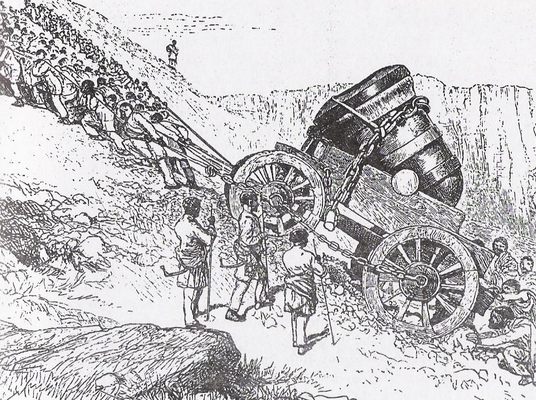

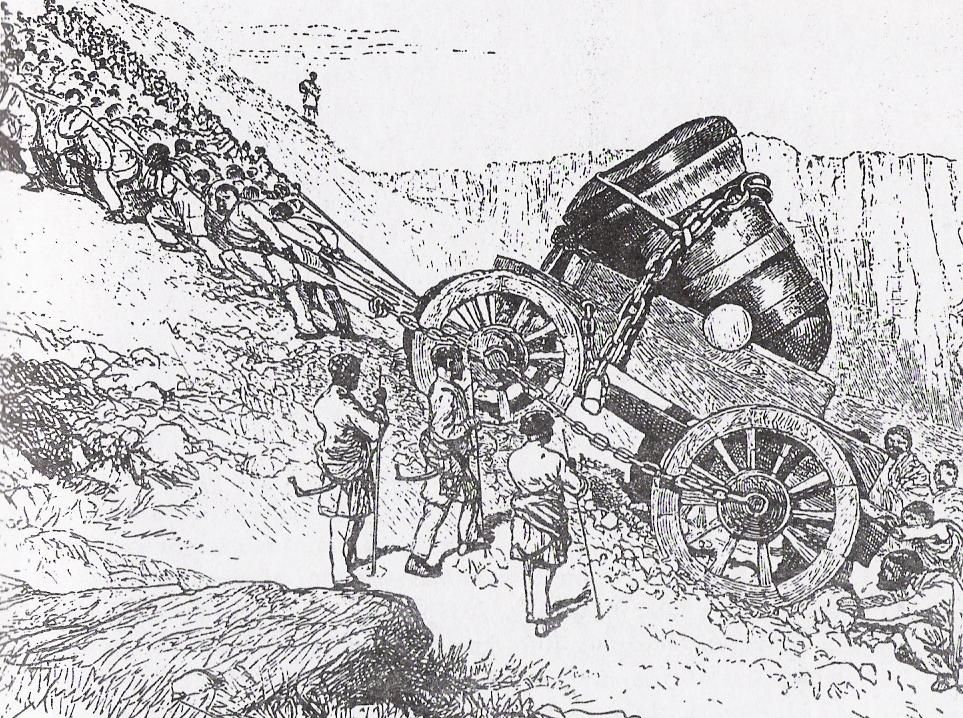

Tewodros moved his forces to the mountain stronghold of Magdala (present-day Amba Mariam), along with his prisoners and his arsenal. Dragging cannons and mortars up the mountainside, however, was no easy feat. Sebastopol alone needed 800 people to drag it up the steepest parts, and what was normally a weeklong journey instead took months.

It was tough going for the British, too, who took nearly two and a half months to cross the arid plains, hills, and mountains on the way to Magdala. But when the two sides finally engaged in battle, British firepower proved devastating. Their new breech-loading Snider rifles obliterated the onrushing musket- and spear-bearing Abyssinian forces.

The artillery that Tewodros had for so long coveted proved next to useless. Many pieces failed to fire, and many others never made it up the mountain. No record exists of Sebastopol ever being used in the battle. If it did make it into a firing position, which itself is unlikely, there’s a strong possibility that it would have misfired.

What is certain is that no one ever had the motivation to bring Sebastopol back down from Magdala. It still sits up on the plateau near the old fortress, green with rust and with only a wooden fence surrounding it. There is, however, a bronze replica of Sebastopol on display at the center of a roundabout at Tewodros Square in Addis Ababa.

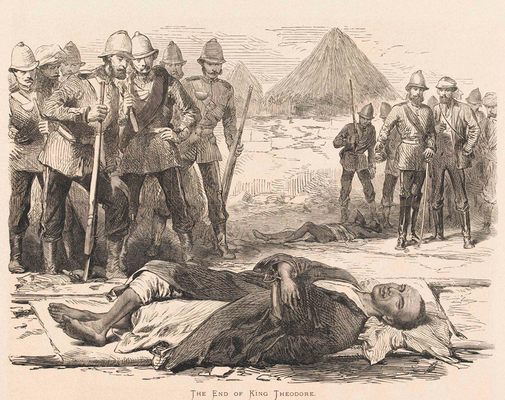

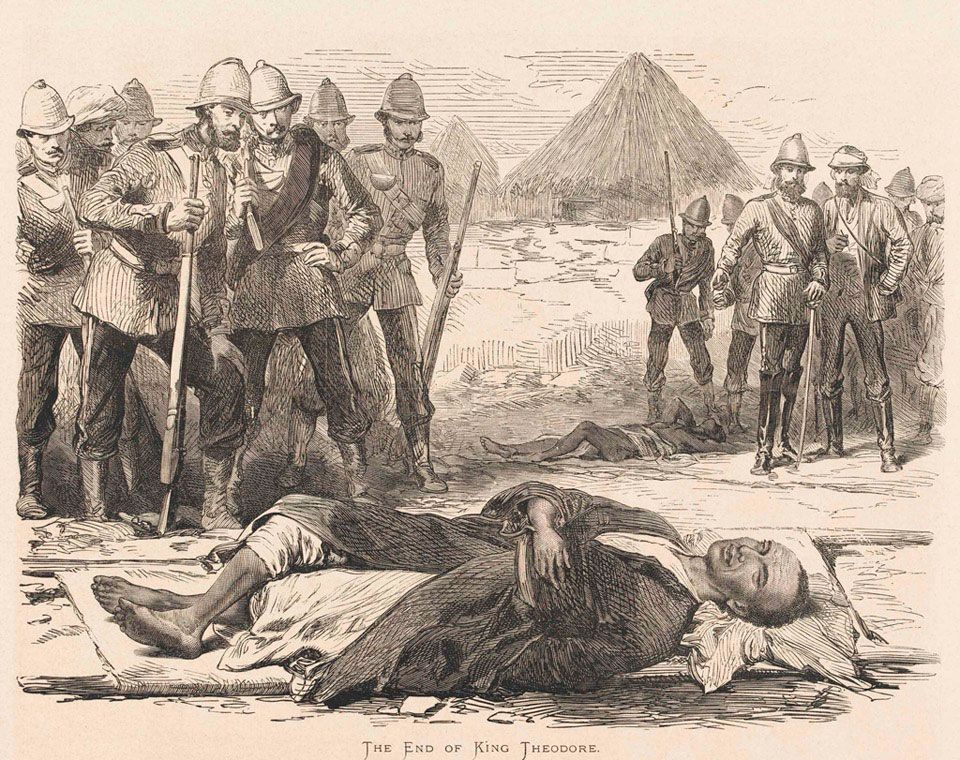

As for Emperor Tewodros II, he retreated to the fortress after his defeat at the Battle of Magdala, released his hostages and then died by suicide. Some claim that he shot himself with a pistol given to him as a gift by Queen Victoria: the only weapon the British monarch ever gave to the Ethiopian Emperor.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

The original Sebastopol mortar sits up on Magdala (Makdala) Hill near Amba Mariam, about 170 miles north of Addis Ababa. Strong trekkers can get their on foot as a long day trip from the town of Tenta, but most visitors take a tent and camp on the hill overnight, where locals can provide water and firewood (but not always food).

If that sounds like too much effort, then you can go see the replica, which stands on Tewodros Square, inside a roundabout along Churchill Avenue in central Addis Ababa.

Published

March 29, 2019

Sources

- https://books.google.com.pe/books?id=7pYpDgAAQBAJ&pg

- http://ehrp.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Clapham-Politics-of-emulation.pdf

- http://ai.stanford.edu/~latombe/mountain/photo/ethiopia-nov-dec-2013/trek-7.htm

- https://academicjournals.org/journal/AJHC/article-full-text-pdf/89D590161236

- https://books.google.com.pe/books?id=DbBm2WpVwUkC&pg

- https://www.military-history.org/articles/war-zone-abyssinia1868.htm