About

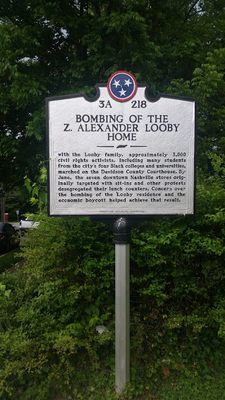

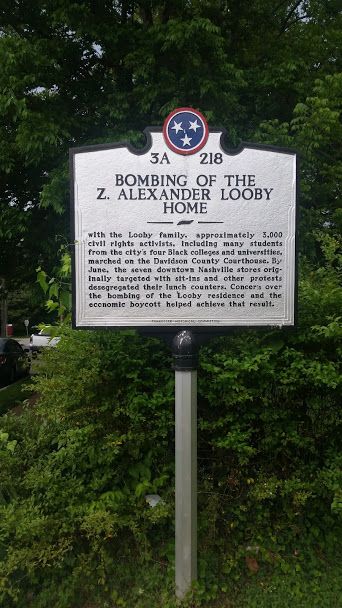

In the early hours of the morning on April 19, 1960, a bundle of dynamite was lobbed towards the front of the house of Z. Alexander Looby, a Nashville councilman and famed civil rights attorney. Rolling onto the home’s concrete foundation, it detonated, the blast destroying the front of the house.

Fortunately, Looby and his wife, Grafta, were asleep in their bedroom in the back of the house at the time of the explosion, saving them from any considerable harm. However, the impact of the blast was so forceful that it obliterated the Loobys’ picture window, severely damaged neighboring homes, and blasted the windows out of the Meharry Medical College buildings located across the street.

The bombing occurred while African Americans were boycotting Nashville’s white-owned businesses, particularly department stores, in protest of segregated lunch counters. This refusal of black Nashvillians to participate in the Easter shopping season successfully put pressure on retailers and politicians, as businesses were seeing unprecedented commercial losses. The attack also came on the heels of sit-in protests at lunch counters, organized by students from the city’s historically black colleges and universities, wherein scores of peaceful protesters were repeatedly harassed and assaulted before being arrested and while in police custody. Looby was one of 13 lawyers who represented these student protesters at trial.

The bombing that targeted the Looby house proved to be a pivotal moment for the civil rights movement in Nashville. It was the catalyst for a march held later that day, in which nearly 3,000 people marched to City Hall in total silence. Once the crowd converged on City Hall, they were met on the steps of the plaza by Mayor Ben West.

There, Diane Nash, a student at Fisk University and one of the key leaders of the Nashville civil rights movement, asked West if he believed that it was wrong to discriminate against a person on the basis of their race or skin color, to which he agreed it was wrong. She then asked, “Mayor, do you recommend that the lunch counters be desegregated?” He replied “Yes,” but with the addendum, “That's up to the store managers, of course.” A watershed moment, this admission by West paved the way for full integration of Nashville lunch counters a few weeks later on May 10, 1960.

Ultimately, the damage to the Loobys’ house and that of their neighbors was so substantial that both had to be torn down. All that remains of the Looby home are the concrete front steps, leading to a now-empty lot, a haunting testament to the struggles faced by black Americans during the civil rights movement.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

You may walk by at any time.

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

May 10, 2019