About

According to legend a young shepherd boy fell asleep in a cave while enjoying his lunch. When he awoke he saw a beautiful woman scamper past the opening of the cave. Entranced by her beauty he ran after her leaving behind his meagre lunch of bread and cheese. Months later he returned to find the cheese had grown a unique blue mold. In a moment noted in gustatory history he took a bite. His daring, so the story goes, led to the creation of blue-veined cheeses.

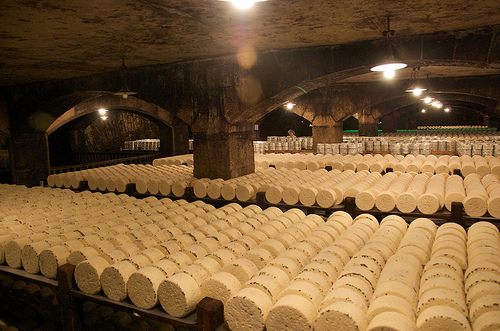

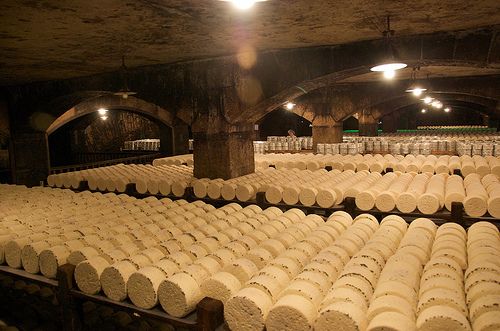

In traditional French cheese-making the cheese-maker leaves a local loaf of sourdough bread, teeming with starter cultures, in underground caves rich with penicillium roqueforti. He lets the bread get moldy then grinds up the moldy loaf and mixes the breadcrumbs with the milk curd. The cheeses are then aged in the caves where the bread went moldy; this encourages the development of blue veins. Most cheese-makers now use a penicillium roqueforti that is made in labs because it makes for more consistent veining.

The name Roquefort is synonymous with the caves in the Averyon department in southern France, where the cheeses are still aged. In order to be legally called "Roquefort," the cheeses must adhere to a number of rules established by the federal standards of the Appelation d'Origine.

Local archeological evidence of cheese-making (mainly ancient cheese strainers) date back to 2000 B.C.E. According to Pliny, the Roman scholar, Roquefort was already world-famous around 76 C.E. Furthermore, these specific caves have been used since at least 900 C.E. for the production of Roquefort.

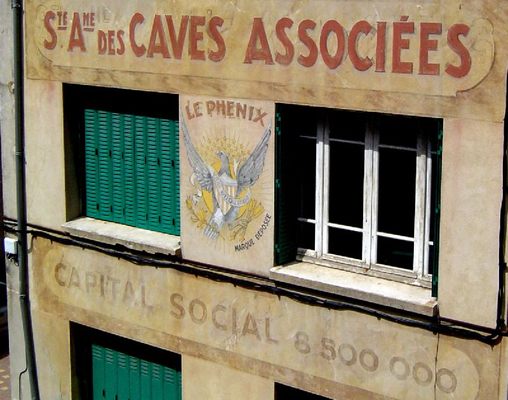

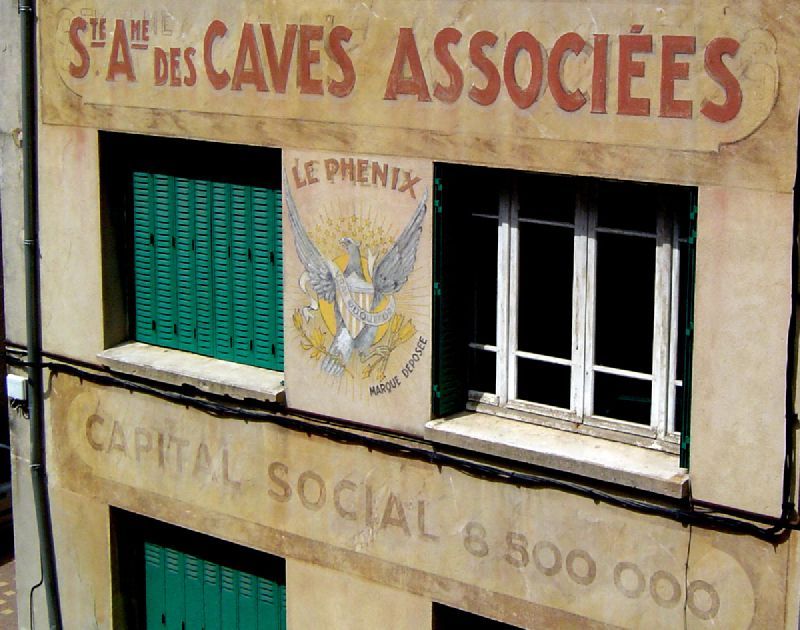

The Société des Caves de Roquefort, where 60% of Roquefort is aged, are open to the public year-round. The hours vary greatly, so visit the website for more details.

Related Tags

Published

September 22, 2009