About

On a day usually set aside for romance and sweet nothings, a trap was set that ended the crime careers of seven men and launched Al Capone straight into the spotlight, as well as directly into the crosshairs of the Feds.

The snare that brought the bloody feud between two Chicago mobster titans to a head turned out to be quite simple. Step One: Invite the North Side Irish Gang out in their Valentine's Day best. Step two: Line them up against a wall like sitting ducks. Step Three: Pull the trigger and hold it down.

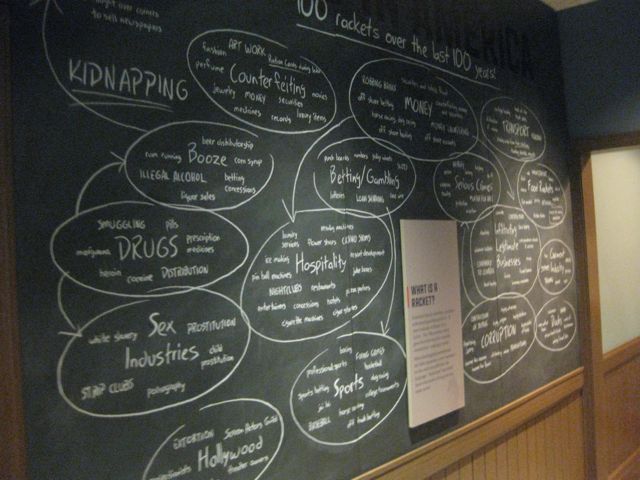

The 1929 massacre of seven members of the North Side Gang horrified the nation with its brutality and careful execution. Bugs Moran and the notorious Al Capone of the South Side Italians had been trying to bump each other off for years, fighting over turf, dog tracks, and hootch, and the community was in constant fear of getting caught in the crossfire. It seemed both men were untouchable, but a failed assassination attempt by Bugs on a fellow named Jack "Machine Gun" McGurn proved to be a fatal mistake, one that in retrospect seems obvious – if you shoot at someone named "Machine Gun" you'd better make sure he's dead.

Capone, not a fan of the chilly northern winters, was vacationing in Miami when McGurn approached him with revenge burning in his belly, and a clever plot to wipe out Bugs and his closest lieutenants to lay on the table. All Capone would have to do was fund the assassination; McGurn had every intention of doing the dirty work himself.

The plan was conceptually simple, and McGurn mapped out every detail carefully. He hired hit men from another gang outside of the city, assuring that Capone's South Side gang wouldn't be fingered. He paid off a hijacker and had him set up a deal that Bugs would be jingle-brained not to take – $57 a case for Old Log Cabin whiskey, a total steal. The plan was that about 10:30am on February 14th, Bugs and his men would go to the warehouse and meet their end, no one the wiser until the bodies were discovered.

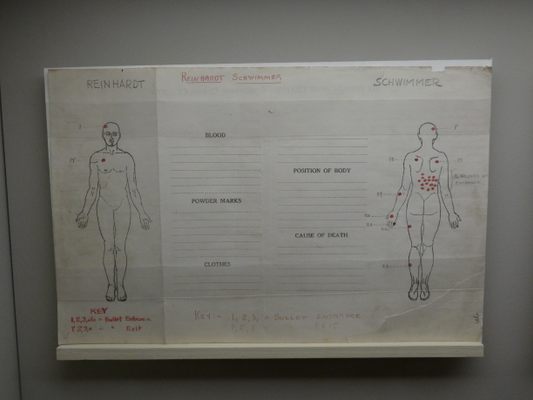

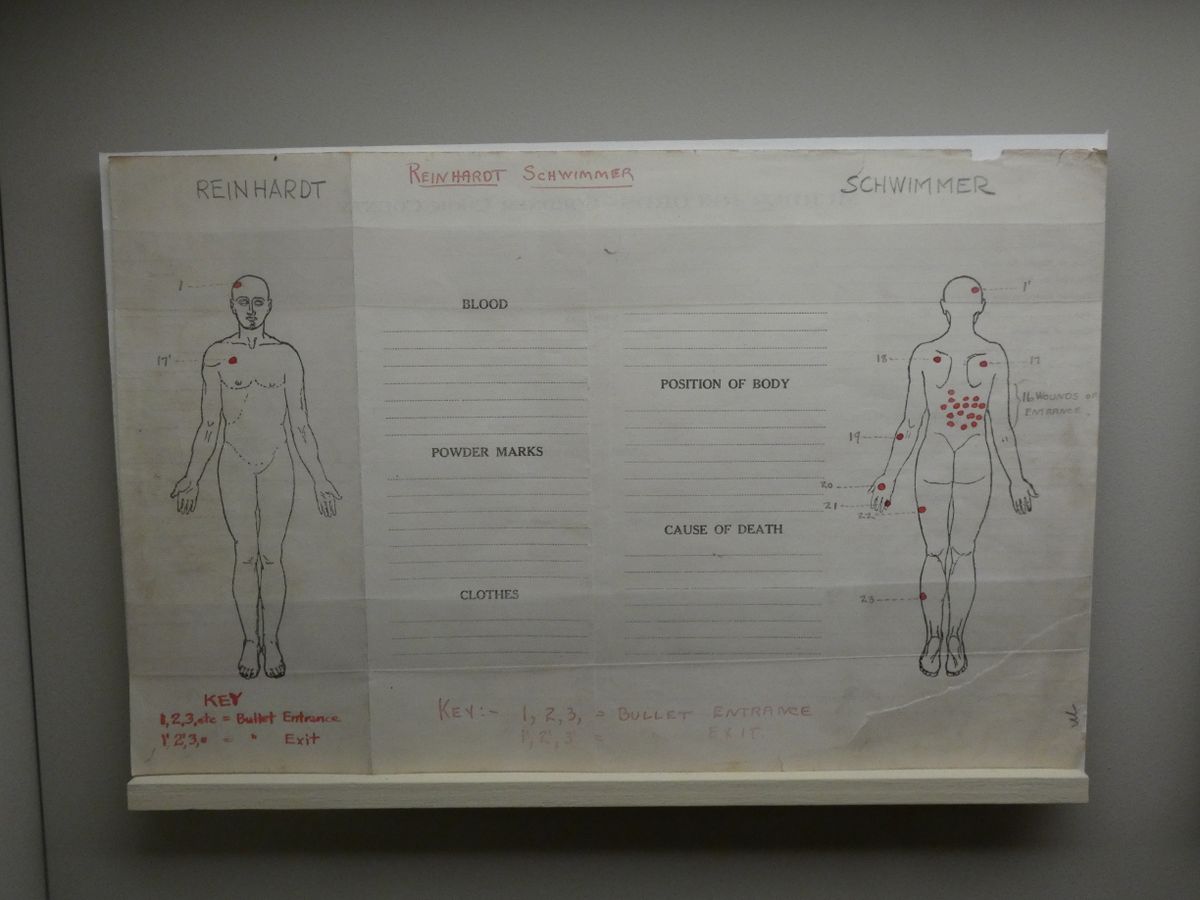

The following details are disputed by historians and gangster enthusiasts, but the undeniable story is that seven men, dressed to the nines, entered the warehouse to do some business. The next thing they knew, a police car had appeared and two coppers had pulled their weapons and told the gangsters to face the brick wall, with their hands up. The men, thinking this was a routine shakedown by the fuzz, did as they were told and turned their backs to the gunmen, hands in the air. Like fish in a barrel, the sizable chunk of the North Side gang was then mowed down by four (some say five) gunmen when the "police" opened fire, and were joined by their plain-clothed co-conspirators. After slaughtering their enemies in an extravagant volley of bullets, the "police" walked their fellow gunmen back out to the stolen patrol car at gunpoint, leaving gawking citizens with the impression that two crooks had just been taken off of the streets by the boys in blue, completely unaware of the carnage left behind.

What appeared to be a seamless plan went off without a hitch, except for one thing – Bugs was not among the men now piled in a bloody heap at the foot of the brick wall. Running late, Bugs had seen the police car and turned back, assuming a sting was going down. The lookout who had given the go-ahead had confused one of Bugs' men, Albert Weinshank, for the mob boss, who shared a similar build.

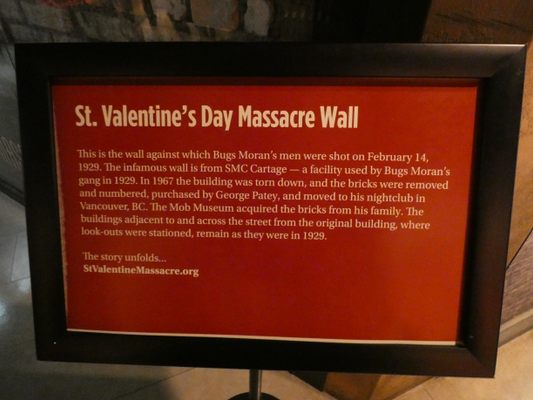

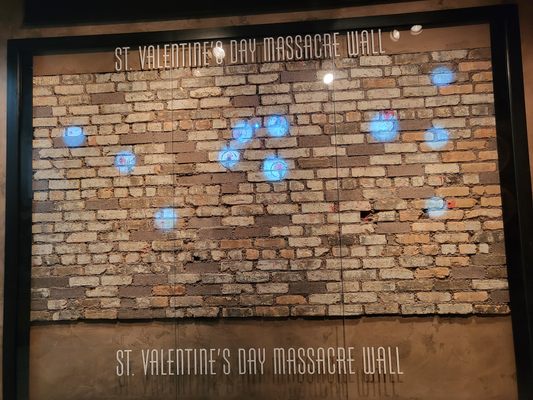

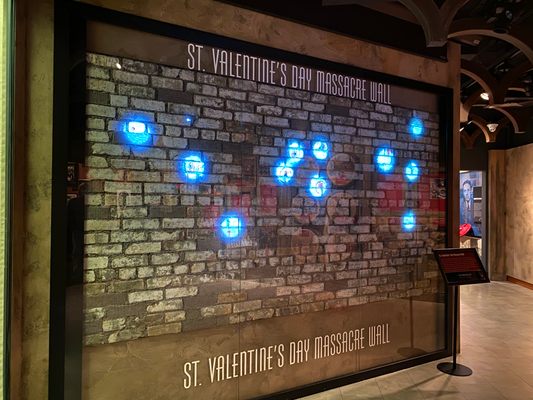

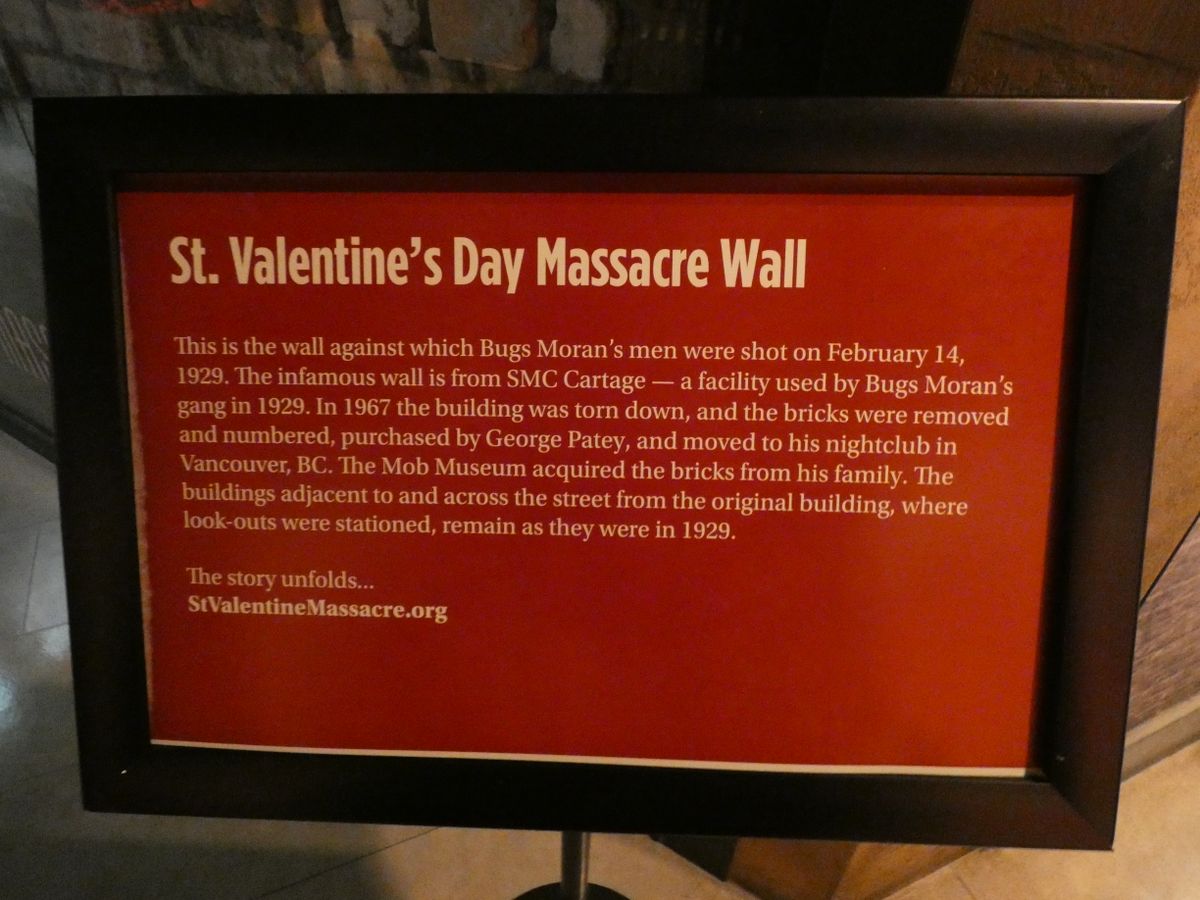

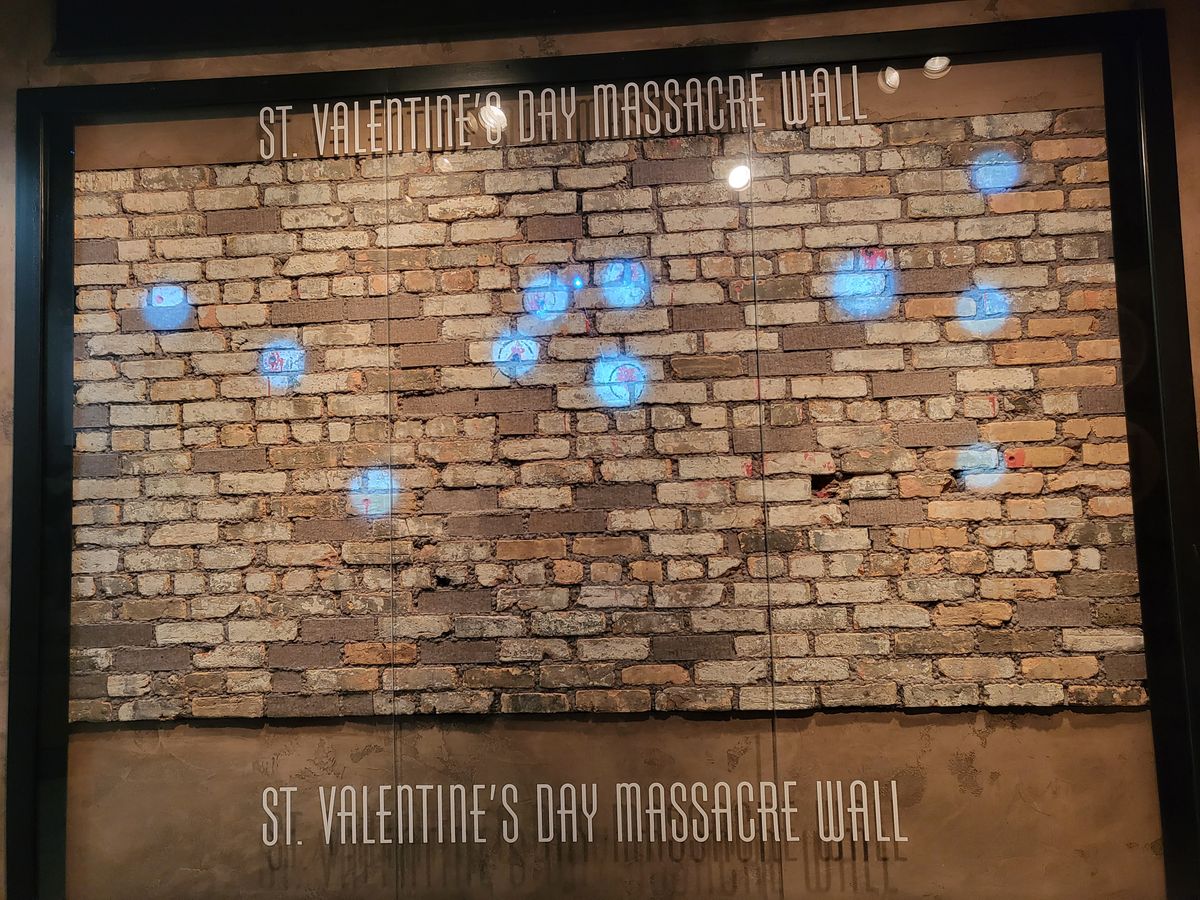

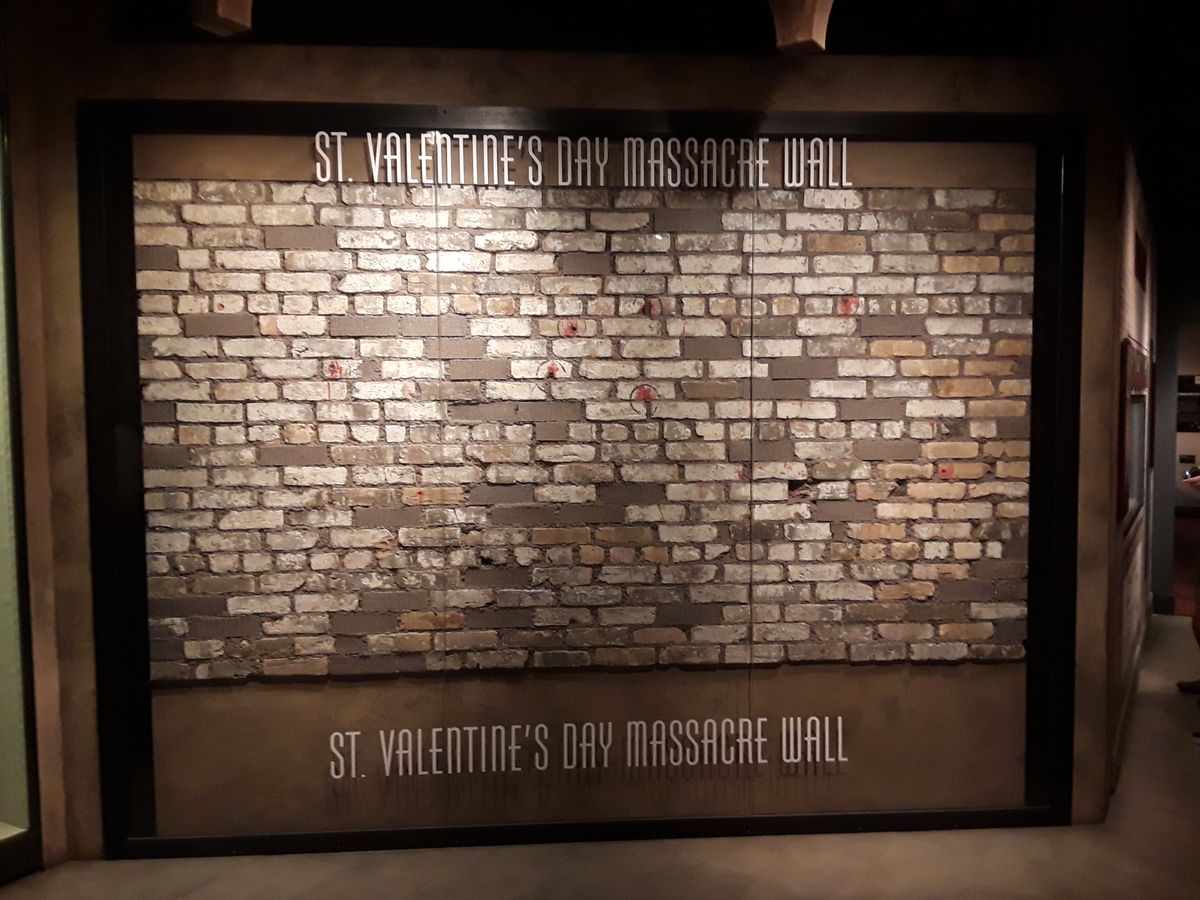

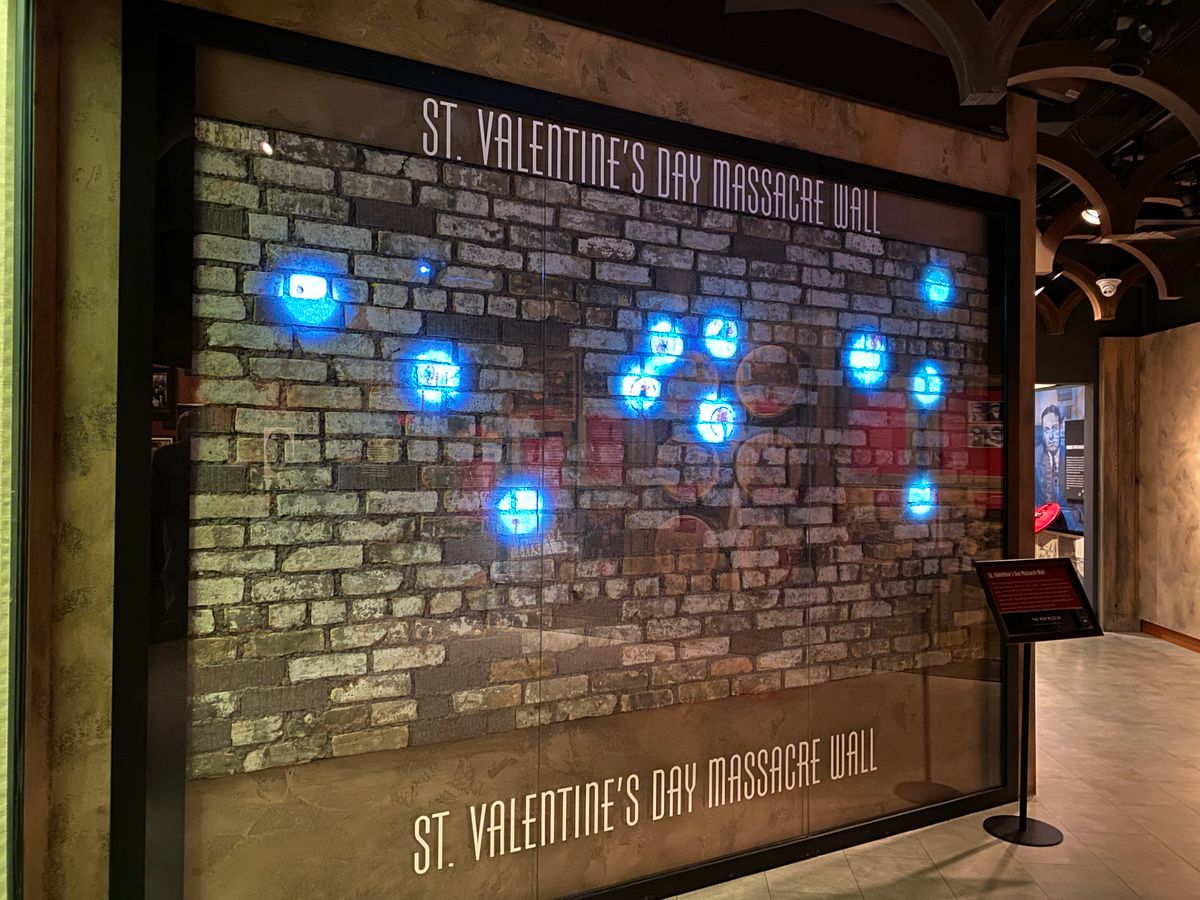

Though the original hit occurred at a warehouse at the corner of Dickens and Clark in Lincoln Park, Chicago, the wall against which this heinous act was carried out has had an interesting life of its own. It was marked as a bad luck omen, and the building was eventually demolished. A Canadian businessman by the name of George Patey snatched up the bricks, hoping to create some sort of money-producing spectacle with them by displaying them in a restaurant or club. Having difficulty selling the morbid novelty idea to business partners, and after years of unsuccessfully trying to turn his ownership of them into a quick buck, he resorted to auctioning them off brick by brick to crime history enthusiasts, who took about 100 of them off of his hands.

When Patey died, the remaining bullet hole-dimpled bricks found a home, someplace they could truly be appreciated – The National Museum of Organized Crime and Law Enforcement, also known as the Mob Museum, in Las Vegas, a three-story repository that covers the entire history of the mob in great detail and was happy to acquire the wall, reassemble it, and display it, complete with an accompanying film and some quick dabs of pinkish-red paint for maximum dramatic effect. The wall is now just one of many authentic artifacts on display depicting the history of one of America's greatest organized crime institutions to date.

Related Tags

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

February 14, 2013