About

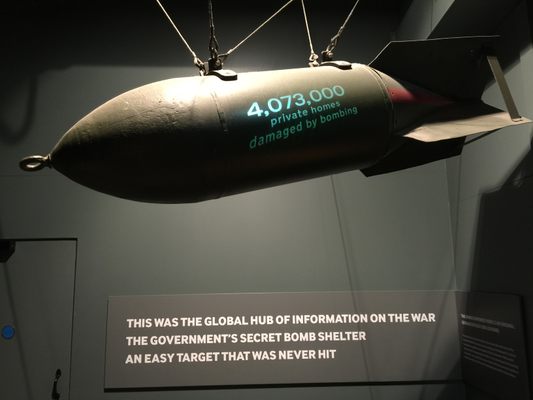

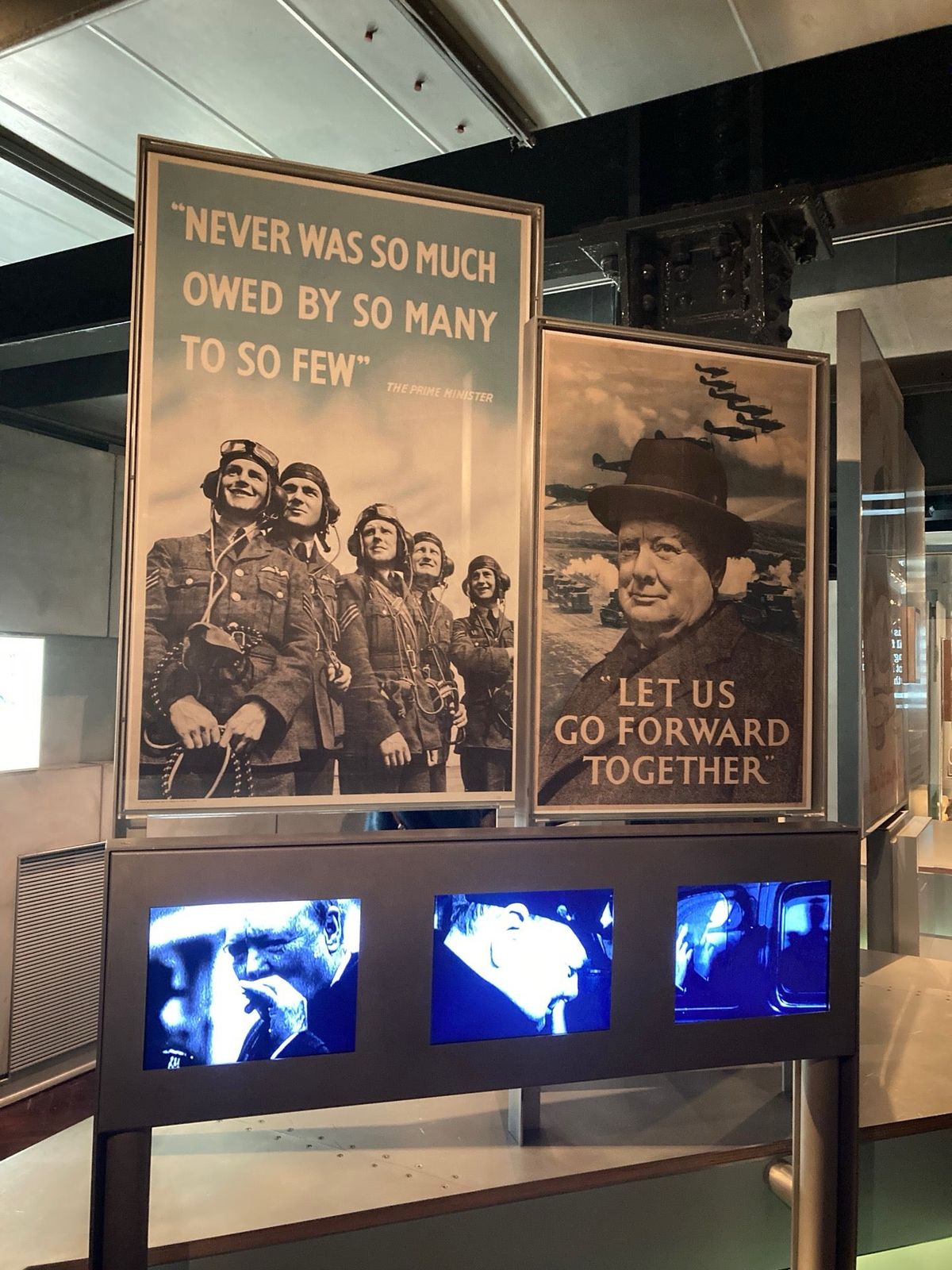

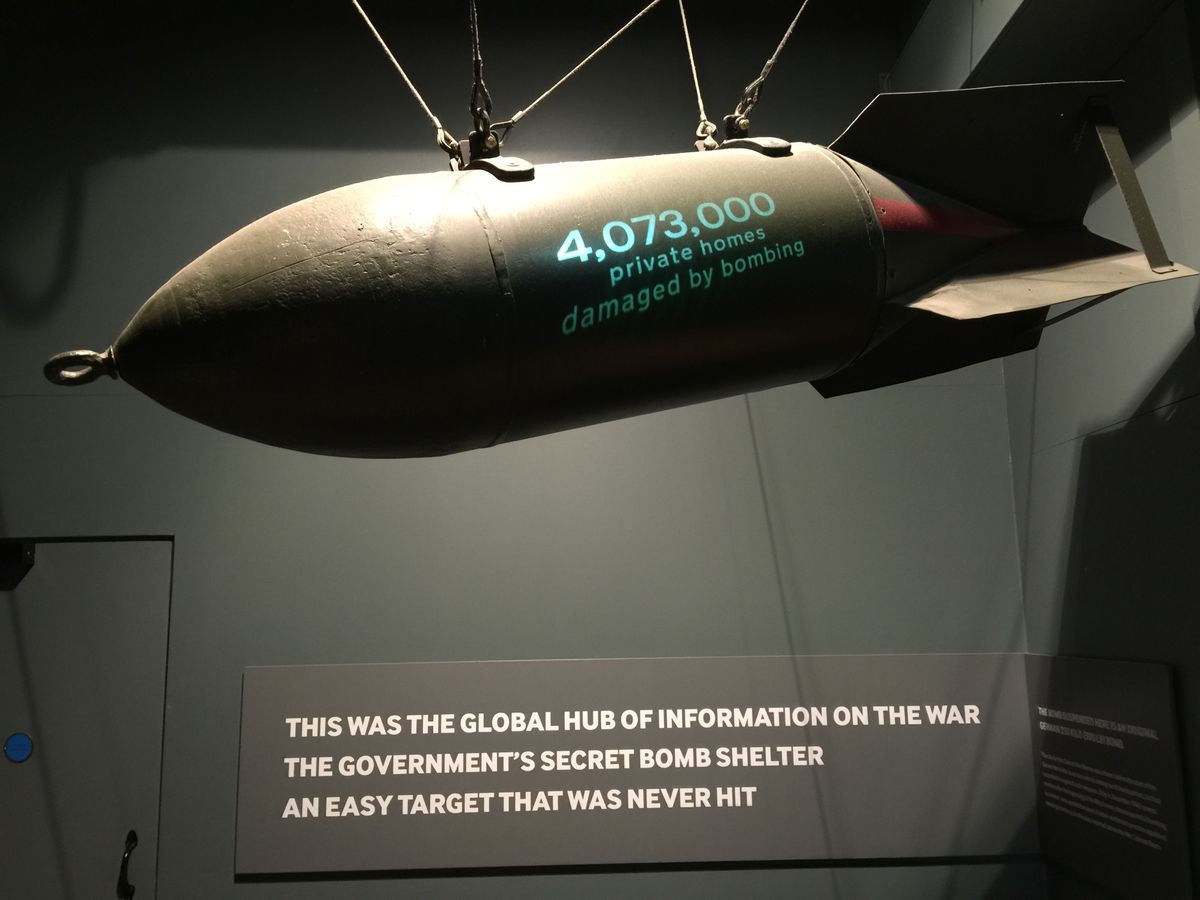

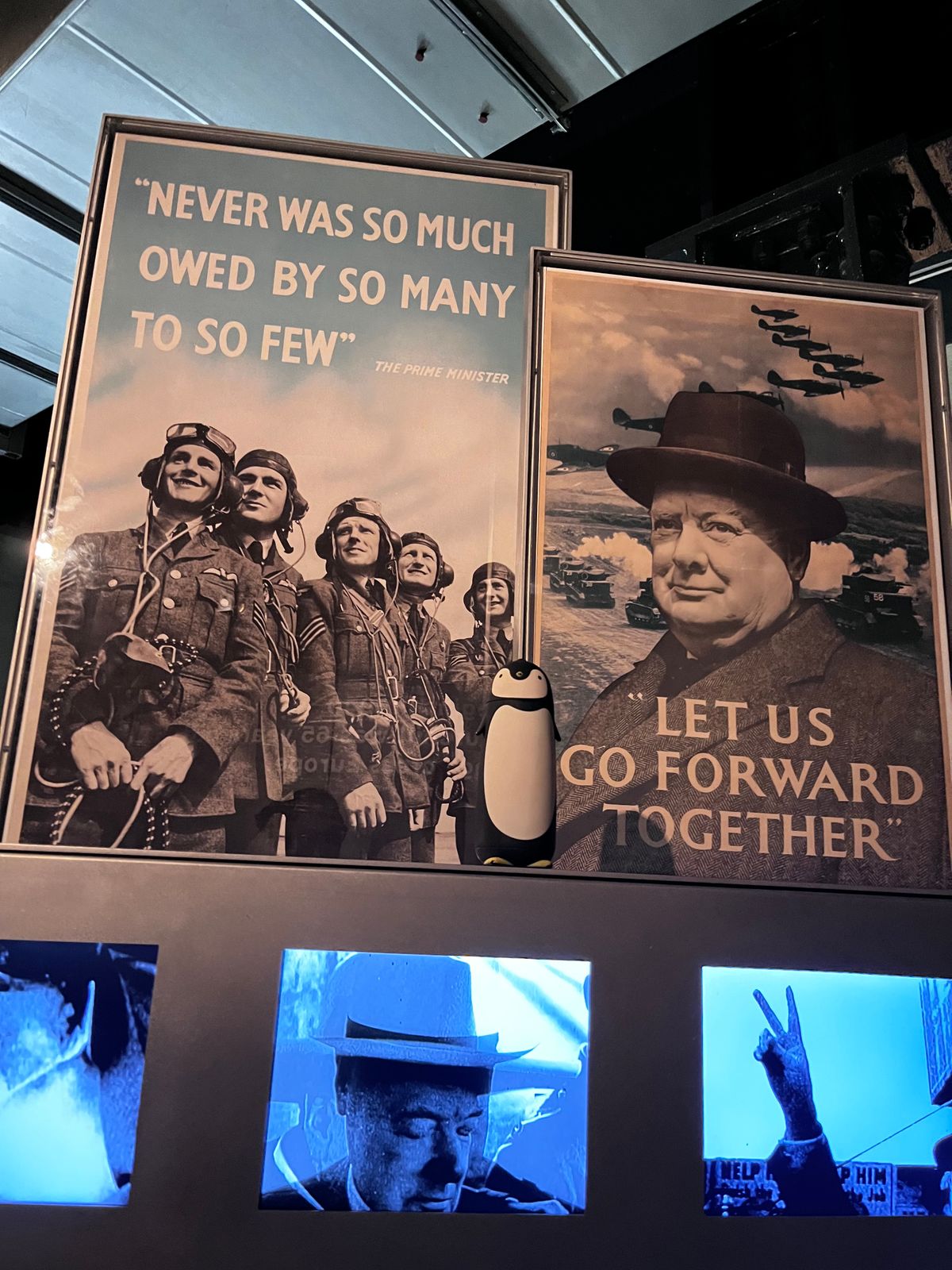

Hidden deep underneath the streets of Westminster lies what was once one of the most secretive and protected parts of London. As the German Luftwaffe pulverized Britain during the Blitz, a system of bunkers and tunnels protected the British government, as Sir Winston Churchill and his chiefs of staff, desperately plotted to secure Britain’s defense against the impending Nazi invasion.

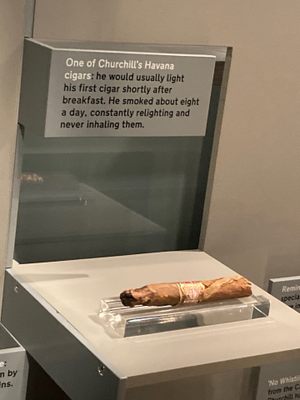

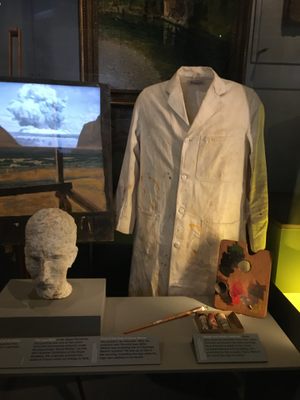

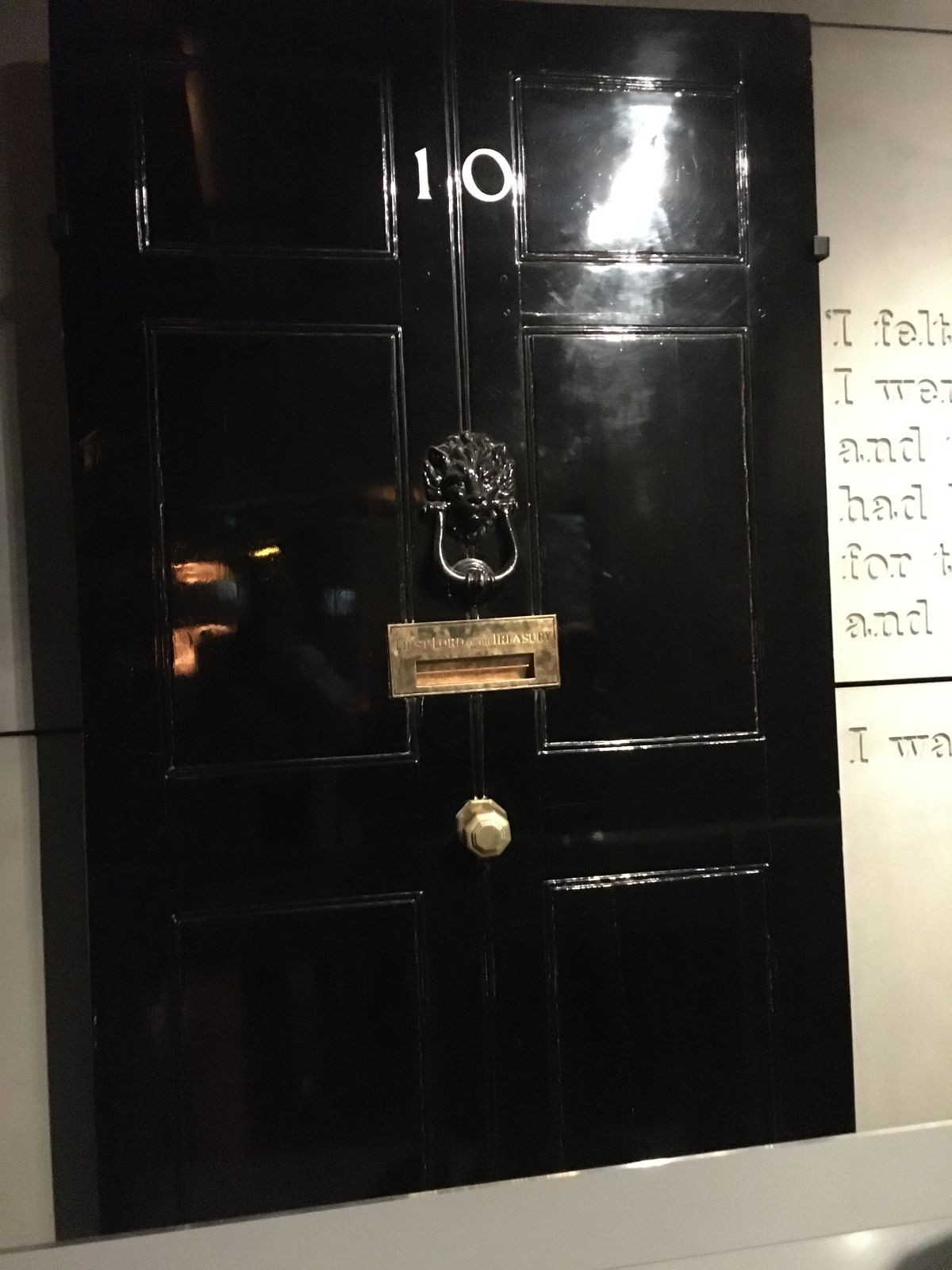

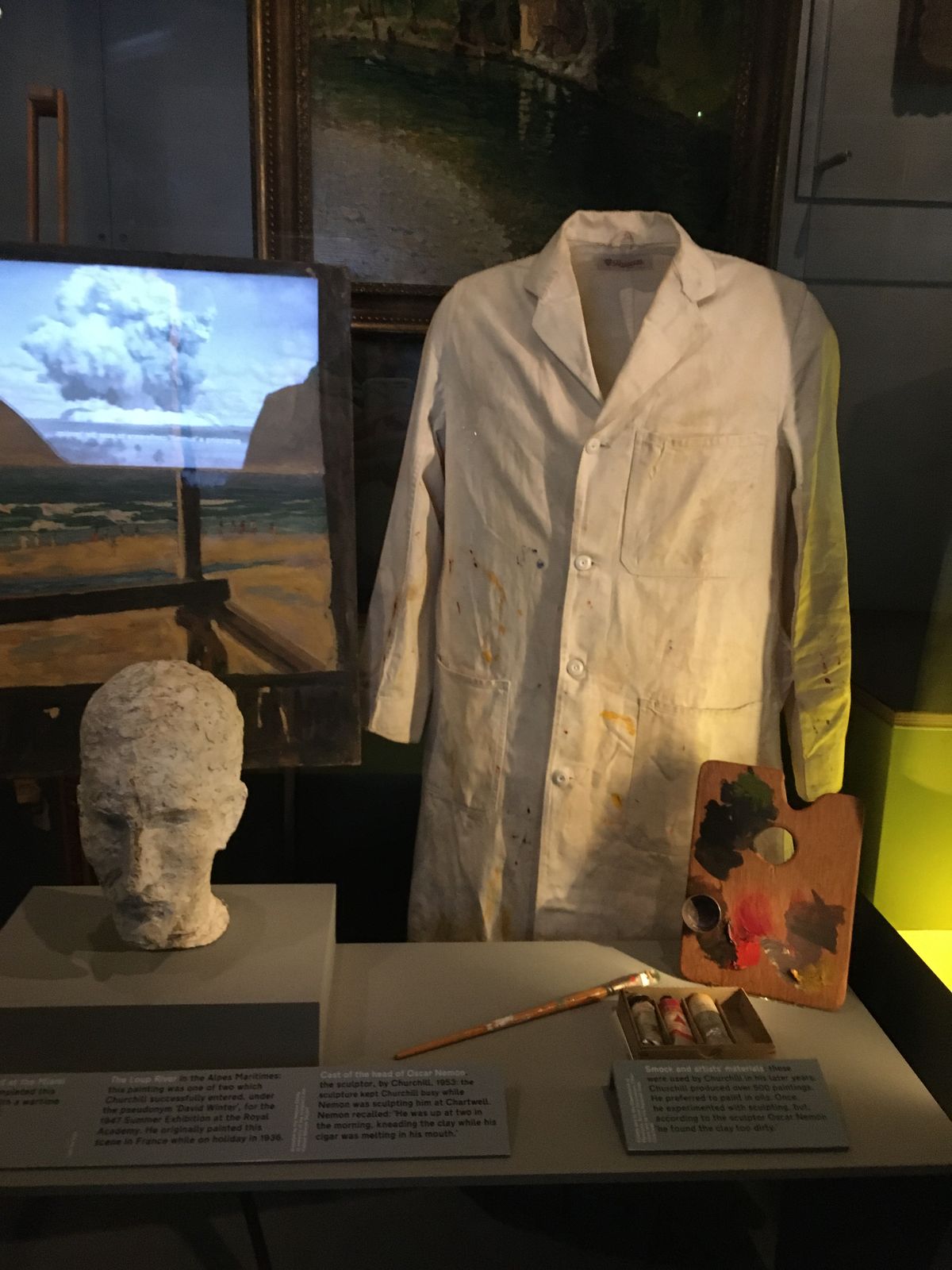

The Churchill War Rooms remain remarkably preserved. After the last V2 rocket hit London, and victory in Europe was secured, the government returned to its daily duties above ground in the Houses of Parliament and the War Rooms were simply sealed up and forgotten. They remained so until 1984 when custody was handed over to the Imperial War Museum and the bunkers were opened to the public. Today, the hidden complex looks just as it did in 1945, as though Winston Churchill had just left the room, and was about to return.

Plans for some form of protective bunker where the government could operate in safety were drawn up, as far back as 1938. The Spanish Civil War had shown what horrors modern aerial bombardment could inflict. As Germany ramped up its military industrial might, the Committee of Imperial Defense began digging underneath the basement of the New Public Offices, located on the corner of Horse Guards Road and Great George Street.

A complex system of bunkers, sleeping rooms, communication equipment and ventilation was burrowed underneath Westminster, and the War Rooms were completed on August 27th, 1939. Just five days later, Germany invaded Poland.

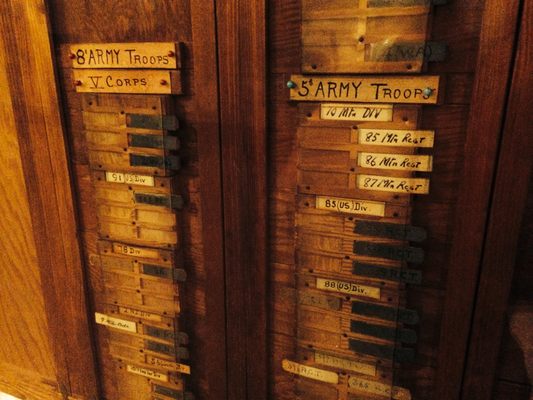

The main brief of the war rooms was to provide the Cabinet with safety whilst they worked. It was also to become the nerve centre of the British war effort, as a meeting place for the Chiefs of Staff for the Army, Royal Navy, and Royal Air Force.

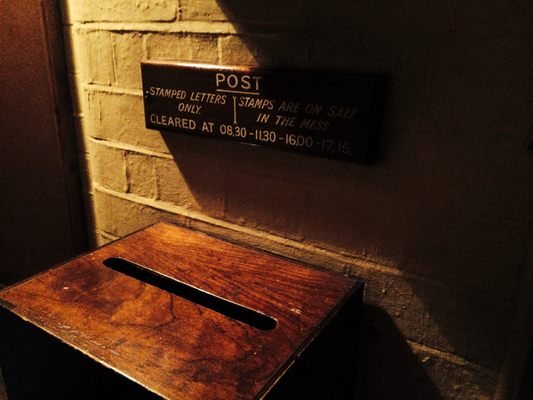

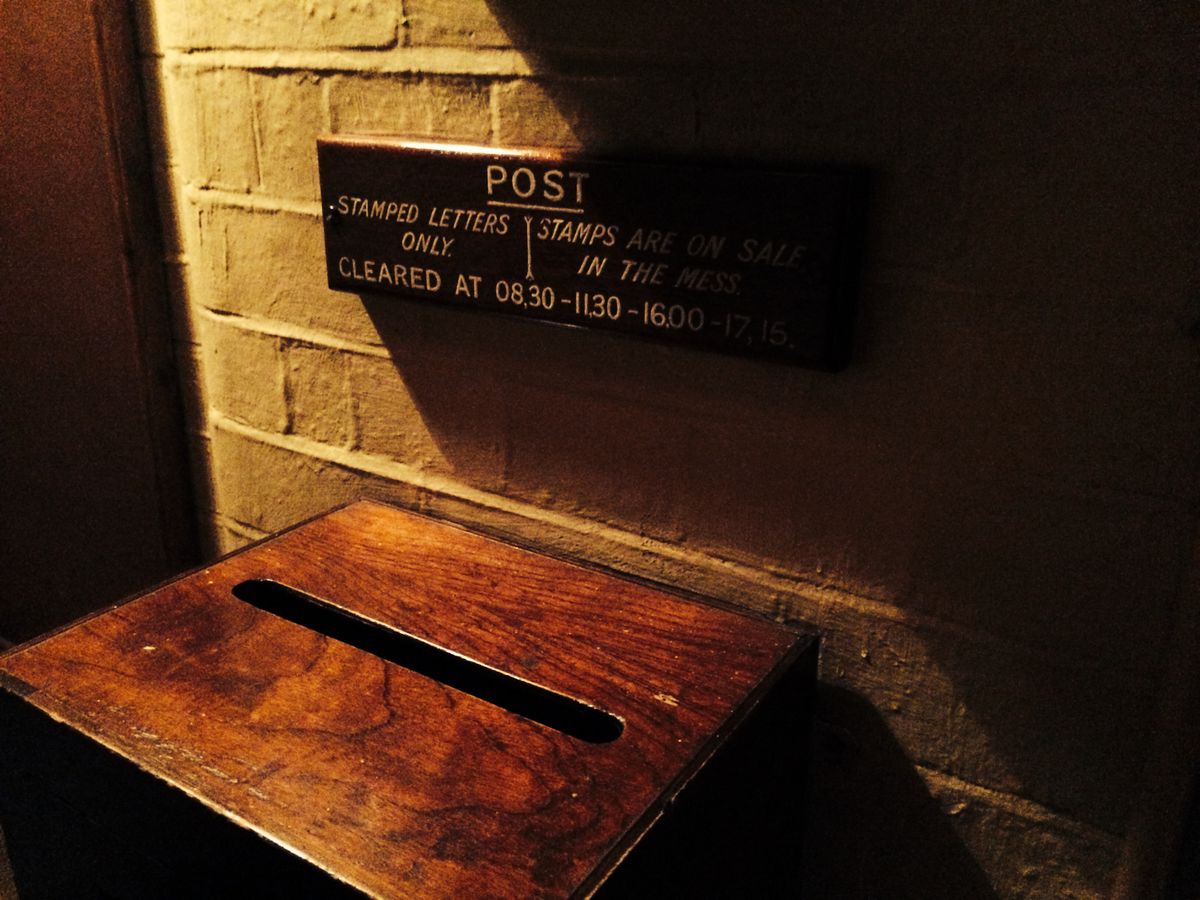

Today, entrance is gained by a small doorway by the Treasury building, under steps marked with a statue of Clive of India. The corridors are narrow, and dimly lit just as they were during the dark days of the Blitz. As wave after wave of German bombers firebombed London with high explosives and incendiaries, the War Rooms aimed to maintain order and calm. One of main corridors still has its weather board in place, where a card strip would indicate whether the day would be sunny, rainy, or cloudy. During air raids, the indicator was always changed to "windy" as a joke.

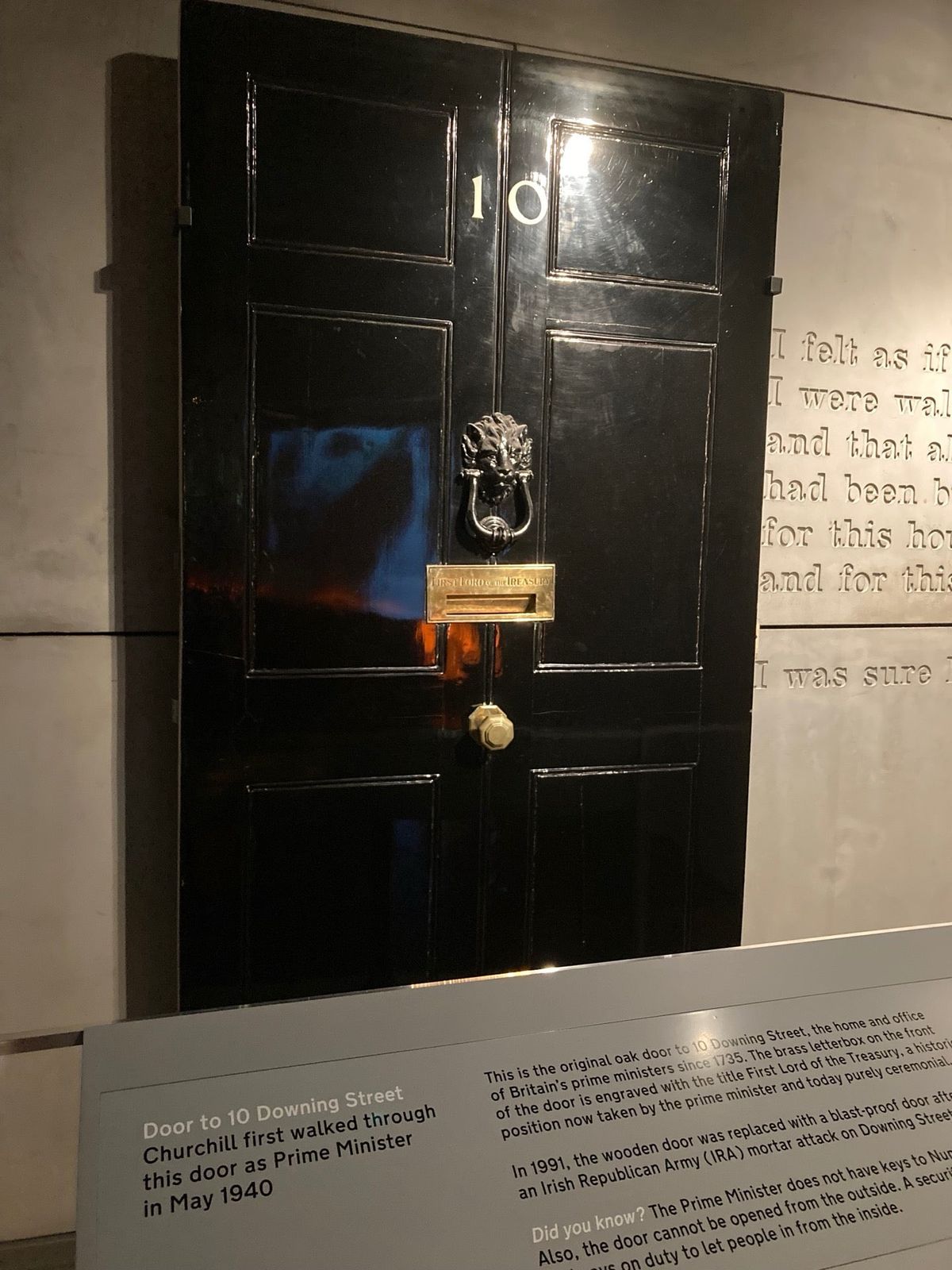

Original plans during the 1930s had mooted the idea of having the Prime Minister and his Cabinet evacuate the City and operate from the country, but it was felt that Londoners would feel abandoned. So the Cabinet would meet daily here underground. The Cabinet Room is left as it was, with Churchill’s chair at the head of the table. The War Cabinet would meet here during air raids, a total of 115 times. But the danger was still deadly. Despite the re-enforced concrete, it is estimated that a direct hit by a bomb of anything over 500 pounds would have completely destroyed the deep lying bunker.

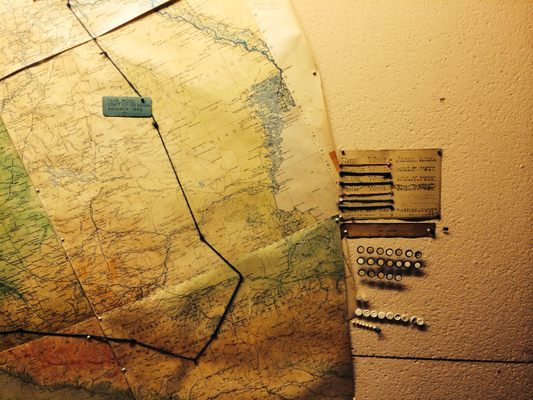

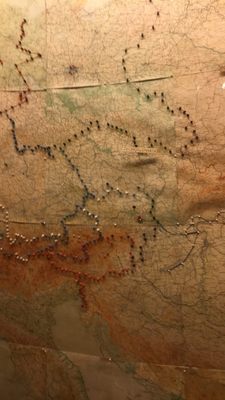

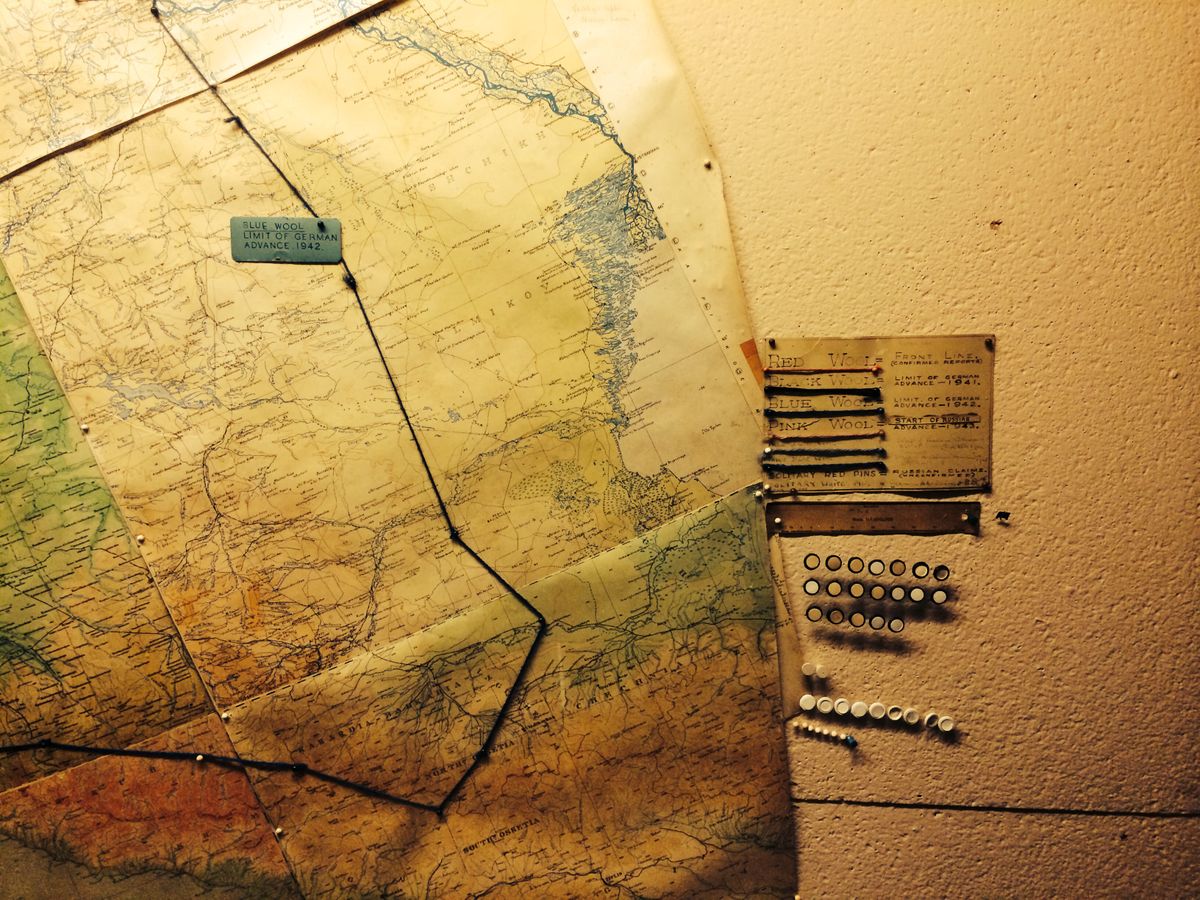

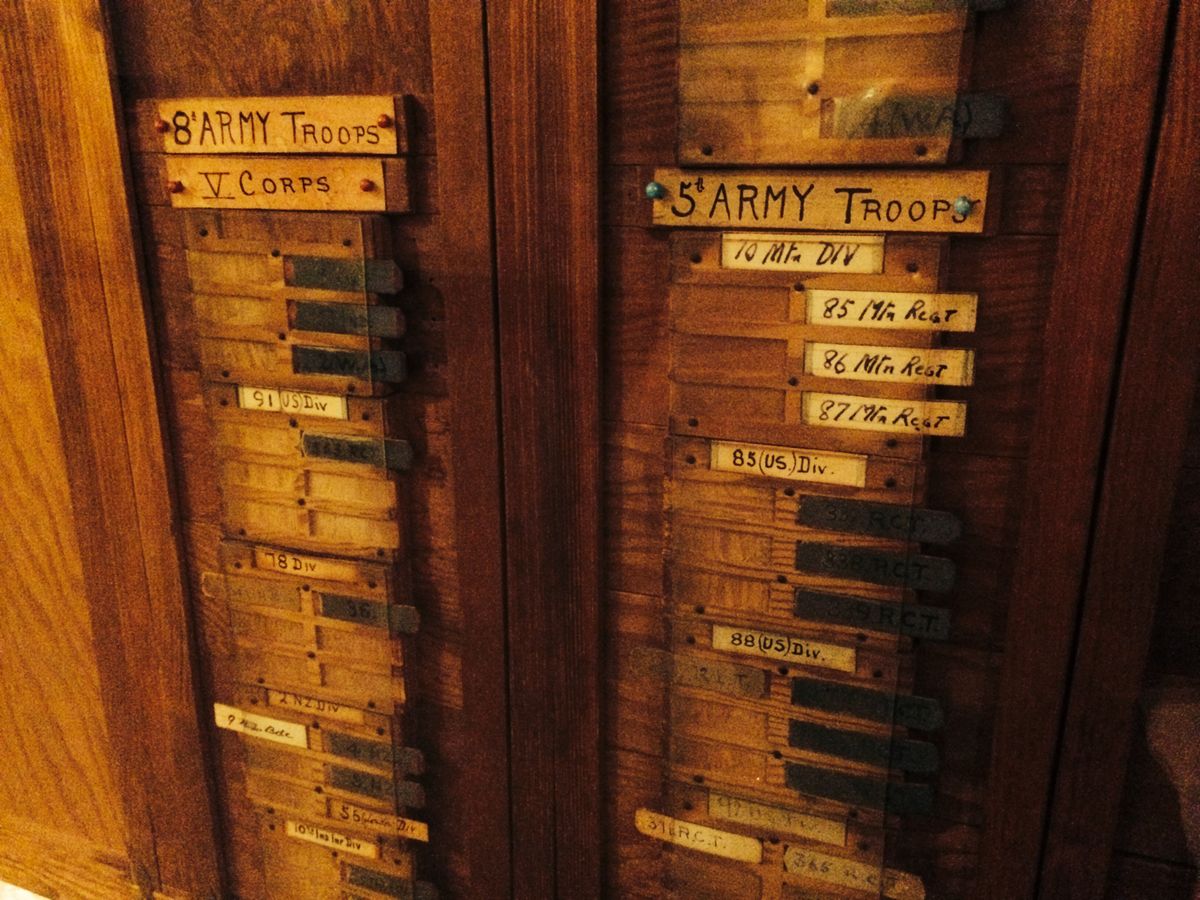

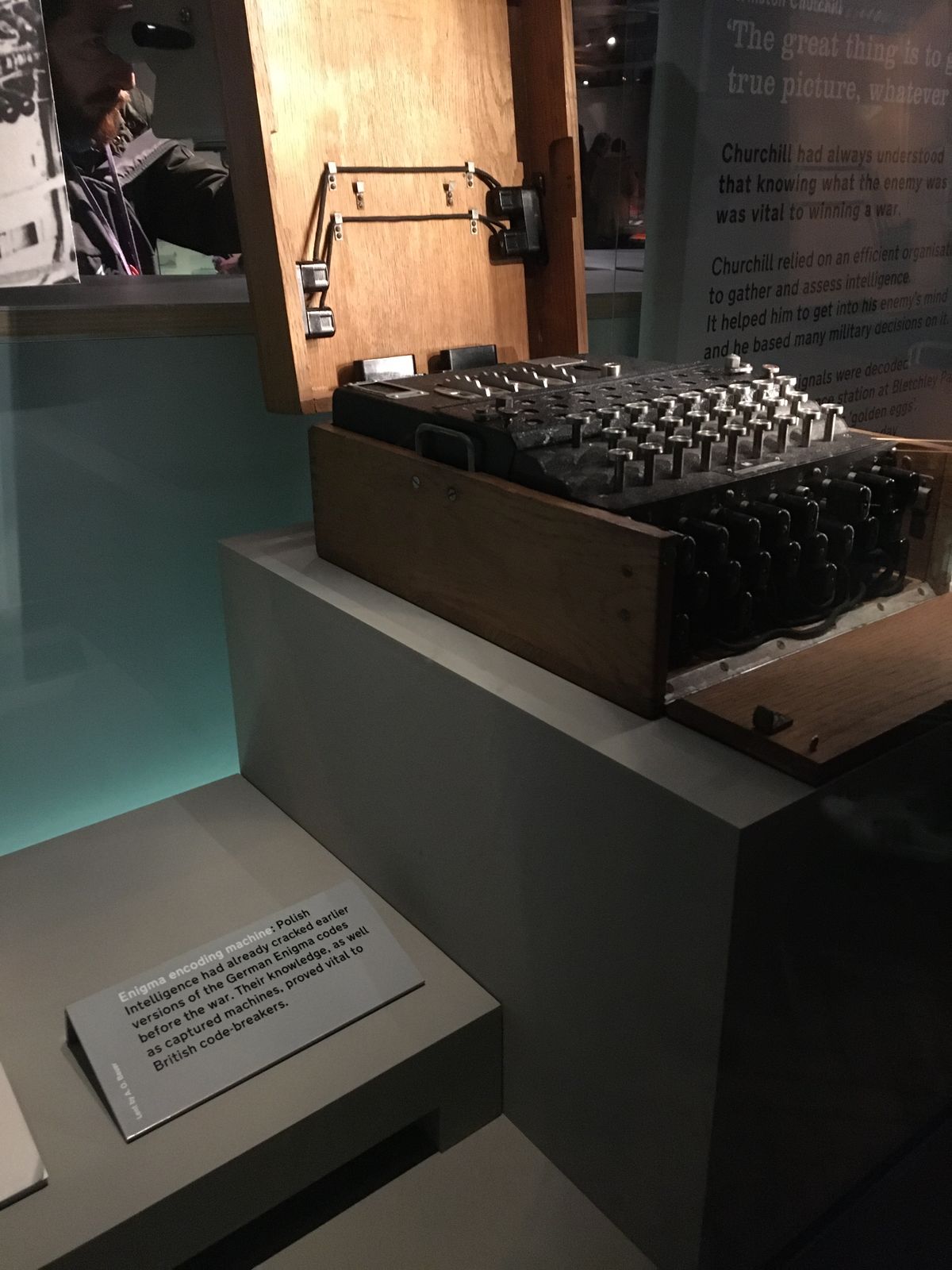

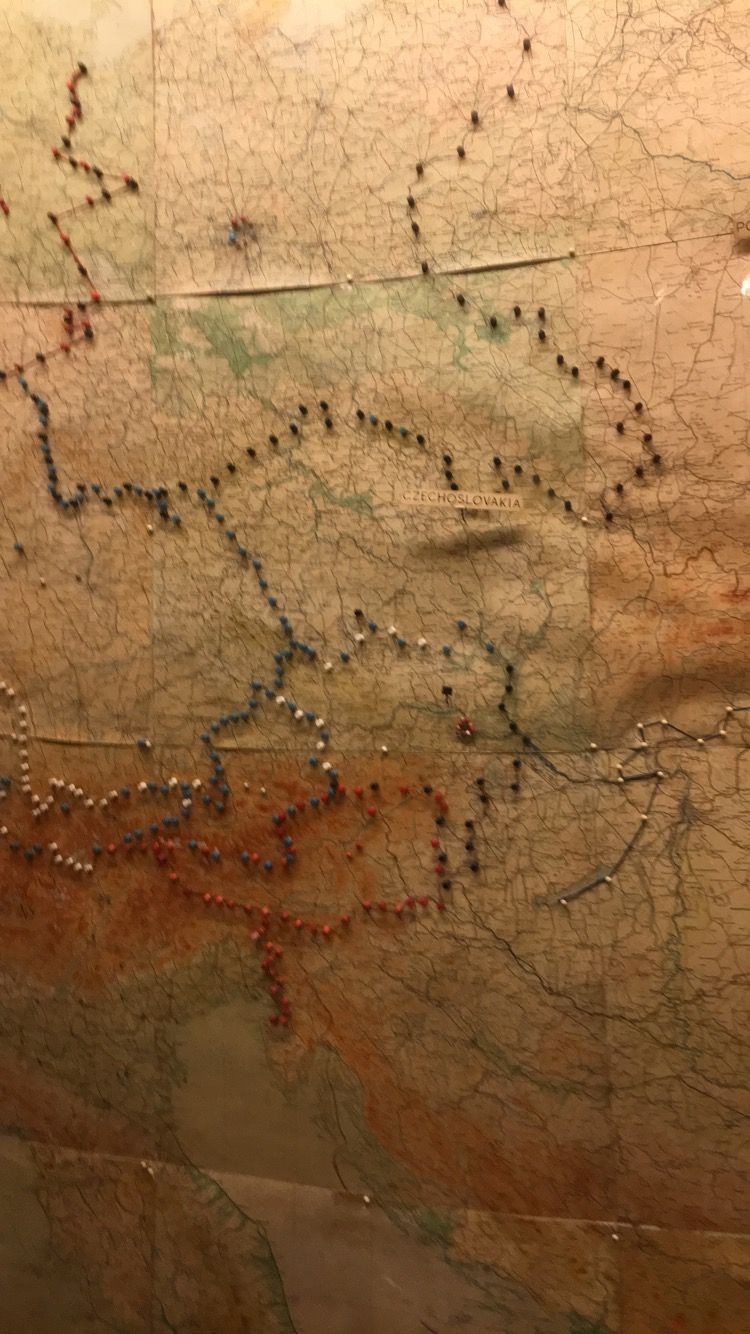

Of equal importance as the Map Room. Here a daily intelligence report of the enemies strength’s and movements were plotted on giant maps. Manned 24 hours a day, the maps also showed the depositions of the British armed forces. Heads of all the armed divisions relied on the up-to-the minute military intelligence depicted on the maps, providing crucial information for King George VI and Winston Churchill. Depicted on the maps by strings of blue wool and pins, the German advance was steadily plotted. By 1940, the foreboding line of blue wool had reached the English Channel itself.

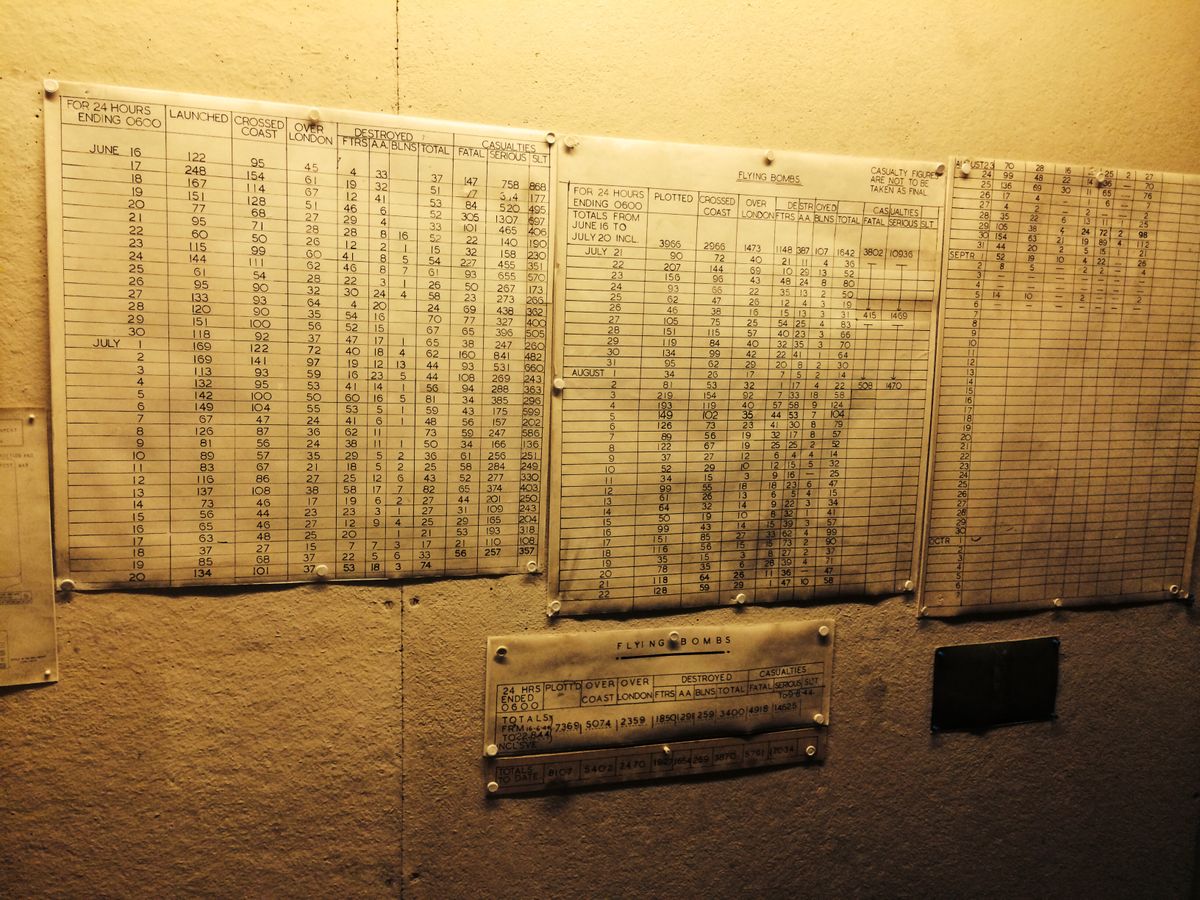

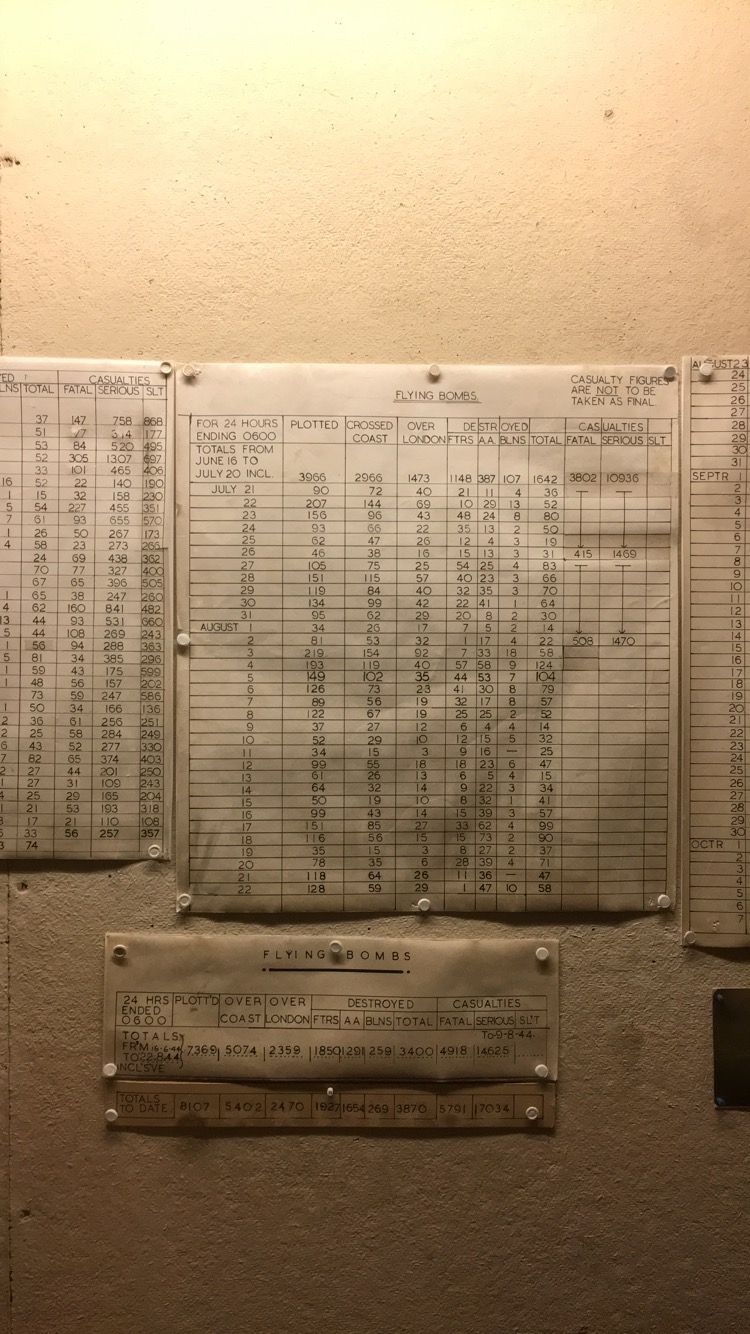

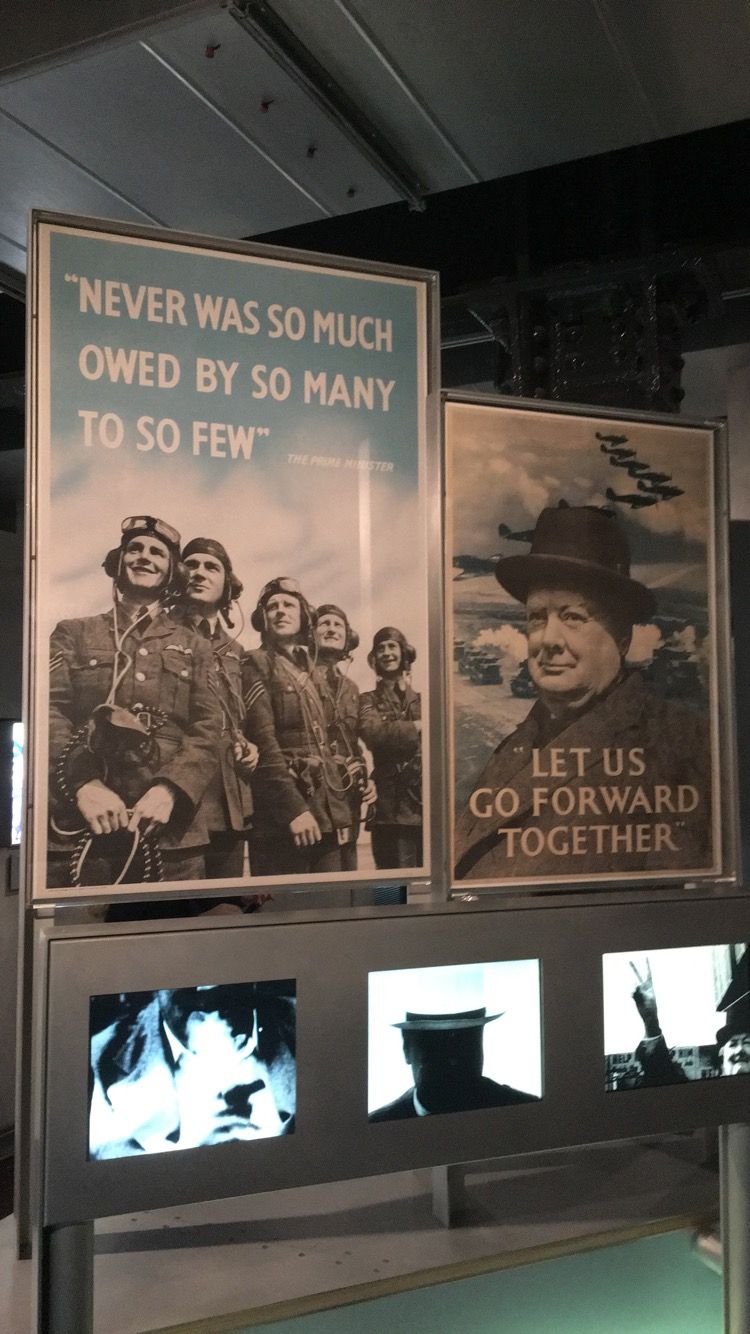

As the Battle of Britain raged overhead, the tension within these hidden rooms must have been on a knife edge. Joan Bright, of the War Office and stationed in the War Rooms described how they had “been shut up inside the fortress of Britain. Blacked out, bombed out, conditioned to austerity.” An idea of the firestorm that fell upon London is given by daily reports of the V1 rocket attacks pinned to the wall of the map room. From June 15th, 1944, to July 20th, the intelligence staff plotted 3,955 of the feared "doodlebugs" launched. Of these, 2,955 crossed the coastline into England.

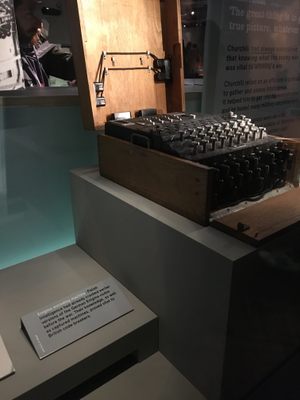

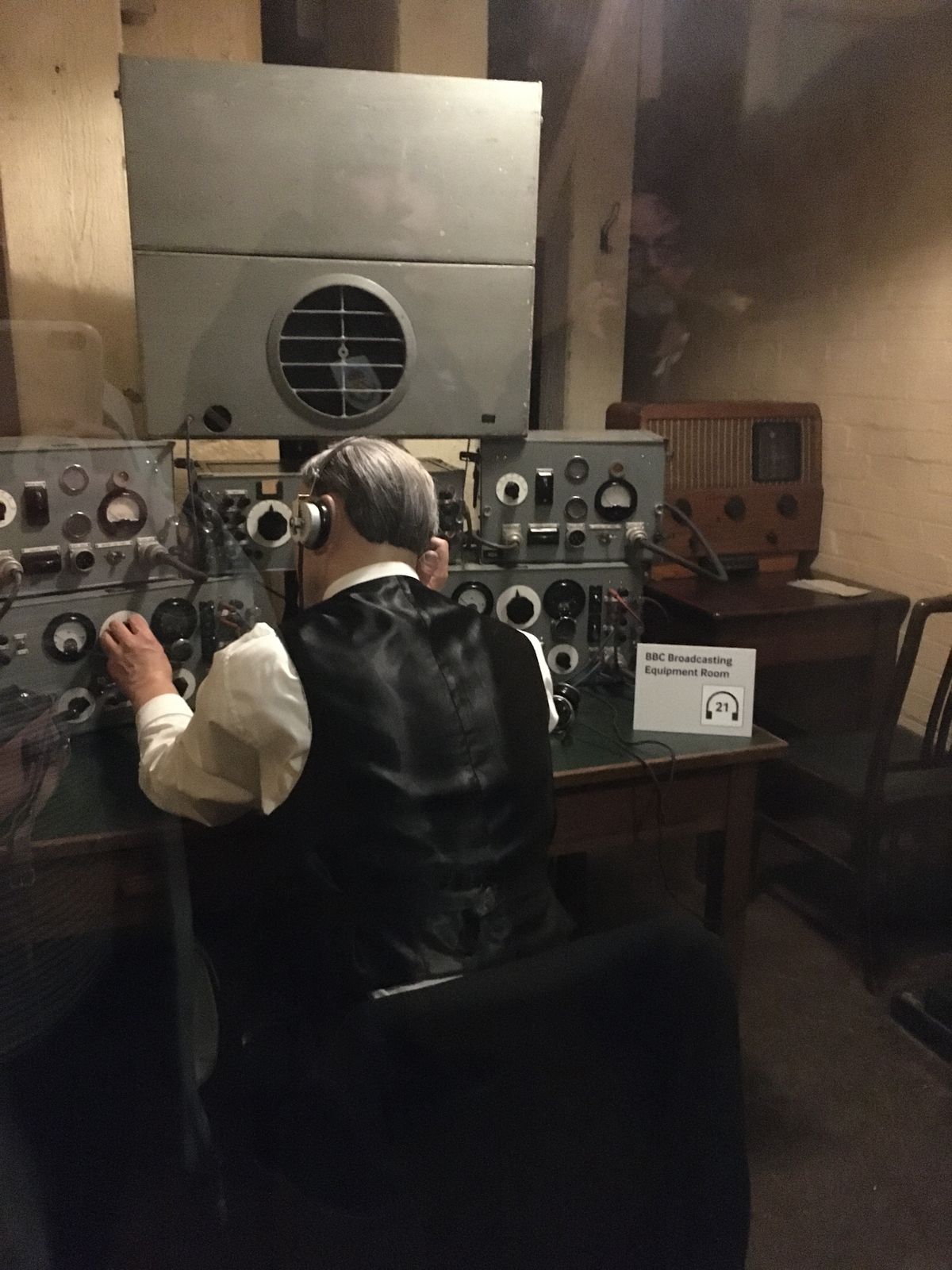

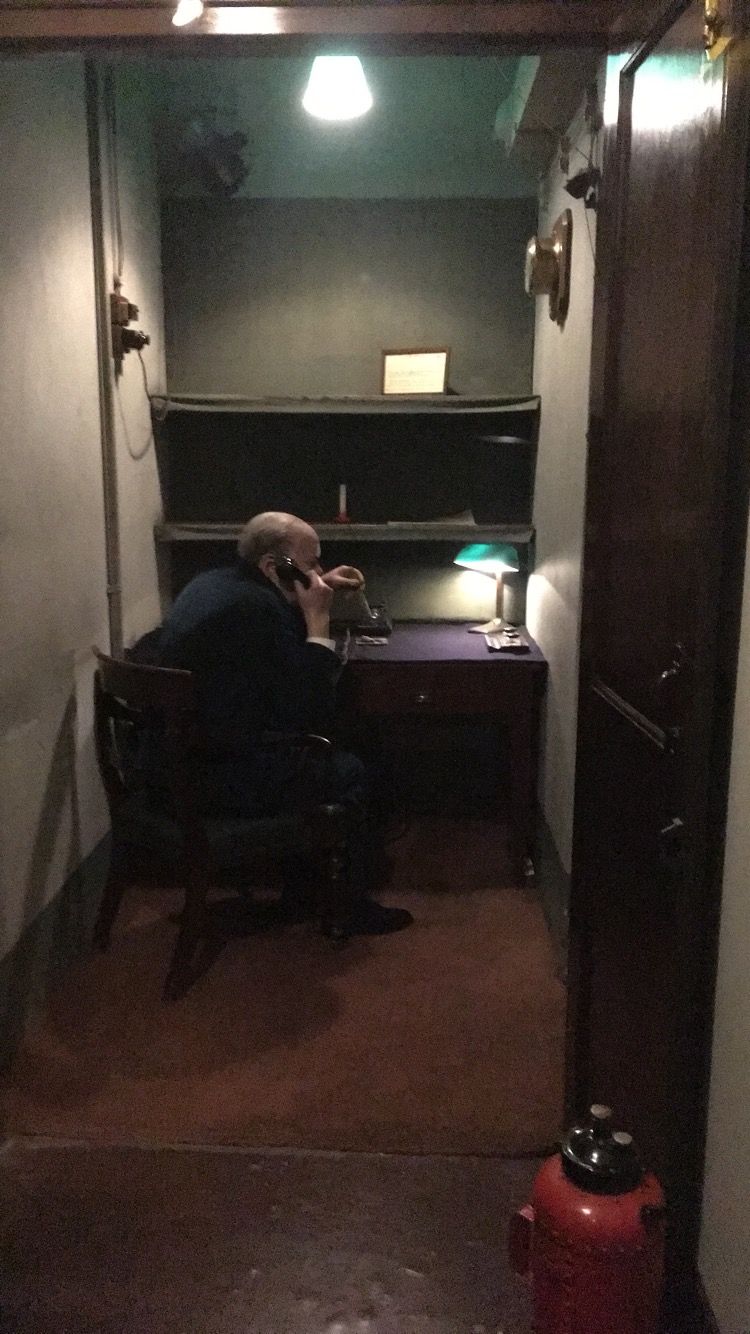

One of the most important rooms in the bunkers was also its smallest. A former broom cupboard housed a telephone that was in turn connected to a vast scrambling device housed in the basement of nearby Selfridges department shop on Oxford Street. Developed in America by Bell, it was the cutting edge of communications technology. For it was in this tiny broom cupboard that Winston Churchill was able to talk directly, and safely, to Roosevelt. The scrambler, codenamed "Sigsaly" opened a vitally important direct hotline between the two leaders without the fear of being tapped by the Abwehr, the German intelligence service.

A visit to the Churchill War Rooms is to step back to a time to when the future of Britain, and indeed the free world, hung desperately in the balance. Immaculately preserved by the Imperial War Museum, the underground headquarters look just as they did when the lights were finally turned off in 1945.

Related Tags

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

February 12, 2016