About

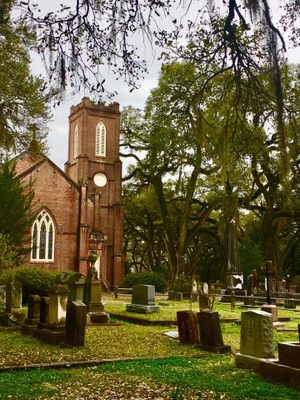

Every summer, Saint Francisville remembers an unusual moment in its history. Against the backdrop of violent national conflict, it was a moment marked, improbably, by ceasefire, rather than bloodshed. At the center of this strange story is the burial ground of Grace Episcopal Church, a drowsy and peaceful spot, where Spanish moss drips heavily from 300-year old branches.

During the most lethal months of the American Civil War, a battle waged over strategic bluffs in Port Hudson. The region was a critical Confederate fortification, charged with blocking the Union warships’ approach to a convergence of the Mississippi and Red Rivers. In March of 1863, the Union warship U.S.S. Albatross was one of two ships to breach this Confederate blockade, under the command of Lt. Commander John E. Hart. In June of 1863, the Union redoubled their offenses on the Port, and the Albatross, led by Hart, took part in this offensive, shelling neighboring Confederate towns, including St. Francisville.

Standing high on a ridge overlooking the Mississippi, about 12 miles from Port Hudson, St. Francisville was an easy target for the soldiers aboard the Albatross, who directed their shells at the gothic structure of Grace Episcopal Church. But on June 12, 1863, the explosions stopped as suddenly as they had begun. A strange silence fell over the town as the dust settled. A wholly different drama had reached its climax aboard the Albatross.

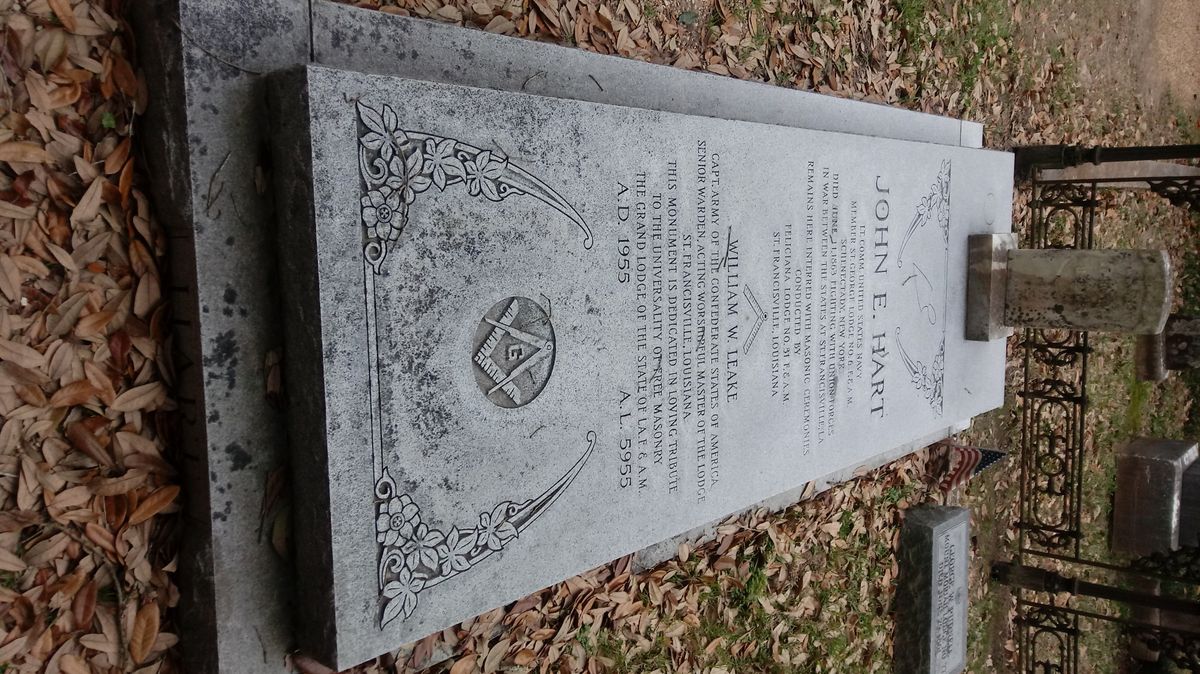

Raving mad with fever, Lt. Commander Hart had taken his own life in the middle of the battle. To the disbelief of the defending Confederate officers, a small boat departed the Albatross, making for shore and bearing a white flag. The request made by the Union boat was an astonishing one: a burial for Lt. Commander Hart in the cemetery of Grace Church, with full Masonic honors.

Along with several of his officers, Hart had been a practicing Mason. The Confederate officer to whom this plea was made, W.W. Leake, happened to be not only a fellow Mason, but also warden of the St. Francisville’s chapter of Masons, the oldest in Louisiana. Sympathetic to his enemies’ request, he arranged for Hart’s burial. A delegation of U.S. Marines, Navy officers and sailors bore Hart's coffin up the steep bluff to the church. Confederate and Union soldiers, as well as Leake and local Masons, observed Hart’s last rites. Thus, with full honors, Lt. Commander Hart was buried in the yard of the church that had recently been used for target practice. And thus, in a moment of bizarre incongruity, enemies found a brief moment of peace and fellowship, amidst the bloodiest chapter of American history.

Another corner of Grace Episcopal Cemetery is the object of local lore. In the back of the cemetery, an empty crypt stands with its door flung wide, inviting those daring enough to venture down its stairs into the darkness. Locals alternately claim that this was a hideout used by Confederate soldiers, or the haunt of a widower who kept it furnished with a rocking chair in order to keep his deceased wife company. Neither claim offers much substantiation and leaves the visitor with more questions than answers.

Hart's burial is reenacted every June as part of a weekend-long program of historic lectures, presentations, and concerts.

Related Tags

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

April 17, 2015