About

The redeveloped stretch of the Hudson River Walkway through Jersey City, offers spectacular views of the West Side of Manhattan. The business district around Exchange Place in particular is a popular vantage point. But amidst the modern gleaming buildings, bars, and park benches lining the waterfront is a truly disturbing memorial.

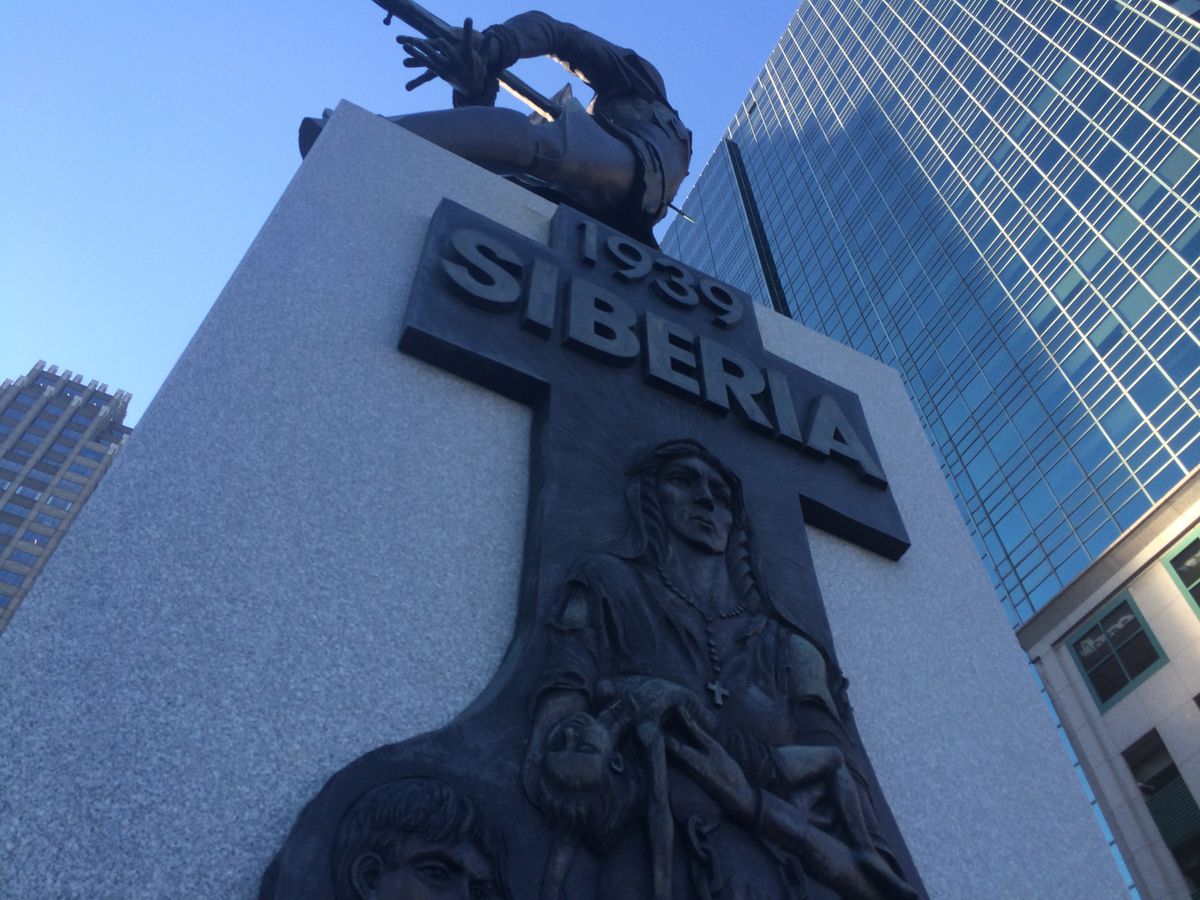

Standing 34-feet high in dull bronze is the figure of a solider, bound forcibly from behind whilst being impaled on a bayonet attached to a rifle which hangs suspended in the Jersey air. Brutal in its imagery, and totalitarian in its execution, the statue of the stricken solider resembles one more commonly found behind the old Iron Curtain. In reality, the violently rendered statue was unveiled in June 1991, just over 50 years after the barbaric event it memorializes.

The desperate soldier with the bayonet sticking out of his chest is a Polish one, and carved on one side, in a bold, sans-serif, Eastern Bloc font are the words, "Katyń 1940." Created by Polish-American sculptor Andrzej Pitynski, the statue commemorates the massacre of over 20,000 Polish soldiers on the orders of Stalin, after the Soviet Union had invaded Poland in 1940.

Katyń was a forest located near Smolensk, where the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs, (the NKVD, forerunners of the KGB), rounded up the prisoners of war and executed them over 28 consecutive nights in a specially made basement execution chamber. Over 7,000 Polish prisoners were personally killed by Vasily Mikhailovich Blokhin, Stalin’s chief executioner, making him the most prolific mass murderer in modern history. Wearing a leather butcher’s apron, Blokhin carried out his terrible work for 10 hours straight each night. The bodies were then interred in mass graves in the forest to be forgotten about.

The statue in Jersey violently captures the terrible events that took place in the forest of Katyń, but its graphically violent imagery speaks to the later controversy that surrounded it. The bound solider symbolizes the non-aggression pact signed between Germany and Russia in 1939, a week before Germany invaded Poland, starting the Second World War. Known for the statesmen who signed it, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact effectively carved the helpless Poland in two between the Soviets and Germany. Poland’s helplessness is captured in his hands tied behind his back.

When Germany turned its forces East, capturing Smolensk in 1942, the mass graves were discovered by the Wermacht. Sensing an opportunity to drive a wedge between the Soviet Union and her Western Allies, Joseph Gobbels seized upon the massacre as a propaganda tool. He brought in a Red Cross committee to investigate the mass graves, gathering forensic experts from all over occupied Europe. Gobbels took to the air in April, 1943, broadcasting worldwide on Radio Berlin about the discovery of a ditch that was "28 meters long and 16 meters wide.... in which the bodies of Polish officers were piled up in 12 layers." Laying the blame at Bolshevik inhumanity it was a direct challenge to the United States and Great Britain’s support of the Soviet Union.

The Soviet response was to blame the atrocities on the Germans.

Being publicly made aware of the terrible war crimes, the Western response was to ignore it. Despite the war having started to protect their ally Poland, Churchill and Roosevelt did nothing. Churchill assured the Soviets in secret that, "we shall certainly oppose vigorously any 'investigation' by the International Red Cross or any other body in any territory under German authority." At the same time he wrote to the British Foreign Secretary, that "we should none of us ever speak a word about it."

In Washington, the emissary to the Balkans, Navy Lieutenant Commander George Earle, reported to Roosevelt that the genocide had certainly been carried out by their Soviet allies. FDR ordered the report to be suppressed and Earle was reassigned to spend the rest of the war in American Samoa.

It was not until 1990 that the Soviet Union finally admitted responsibility for the act of genocide committed 50 years before. Perhaps the message of the statue is not so much the helplessness of Poland after the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, but of the failure of their Western Allies to do anything but brush it aside.

Related Tags

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

April 10, 2015