About

In New York City's Central Park, just below the 79th St. Traverse, lies a heavily wooded area, interwoven with narrow, winding trails, and dotted with large granite boulders.

While The Ramble, as it is known, may appear to be the most natural place in the city it only appears that way thanks to the efforts of Central Park's planners Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, as well as the original builders of the Park who put in countless hours constructing a landscape that would seem rustic and remote. But for all their hard work, Central Park has changed. Like everything else in New York City, the Park is constantly evolving. But if you know just where to look, you can still find traces of its original features. One of the more interesting cases is that of the long-lost Ramble Cave.

The Ramble Cave was not part of Olmsted and Vaux's 'Greensward Plan', their design for what would become Central Park. They did lay out the Ramble, complete with paths and trees, but to construct their artificial wilderness required a lot of construction and excavation. It was during one such dig that a large deposit of “rich mould” was found in a small bay on the north side of The Lake ('mould' in this case being extremely fertile soil, not what you find on bread that's been sitting on your counter for too long). The mould was carried away, cart-full by cart-full, revealing a narrow cavity, at water level on the lake-side and sloping uphill thirty feet or so to the north, meeting up with a planned path just to the east of the Ramble Arch.

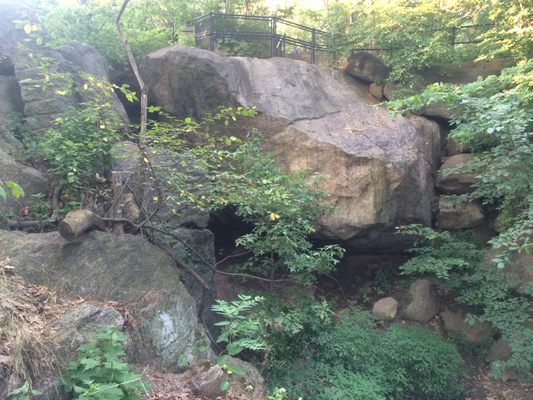

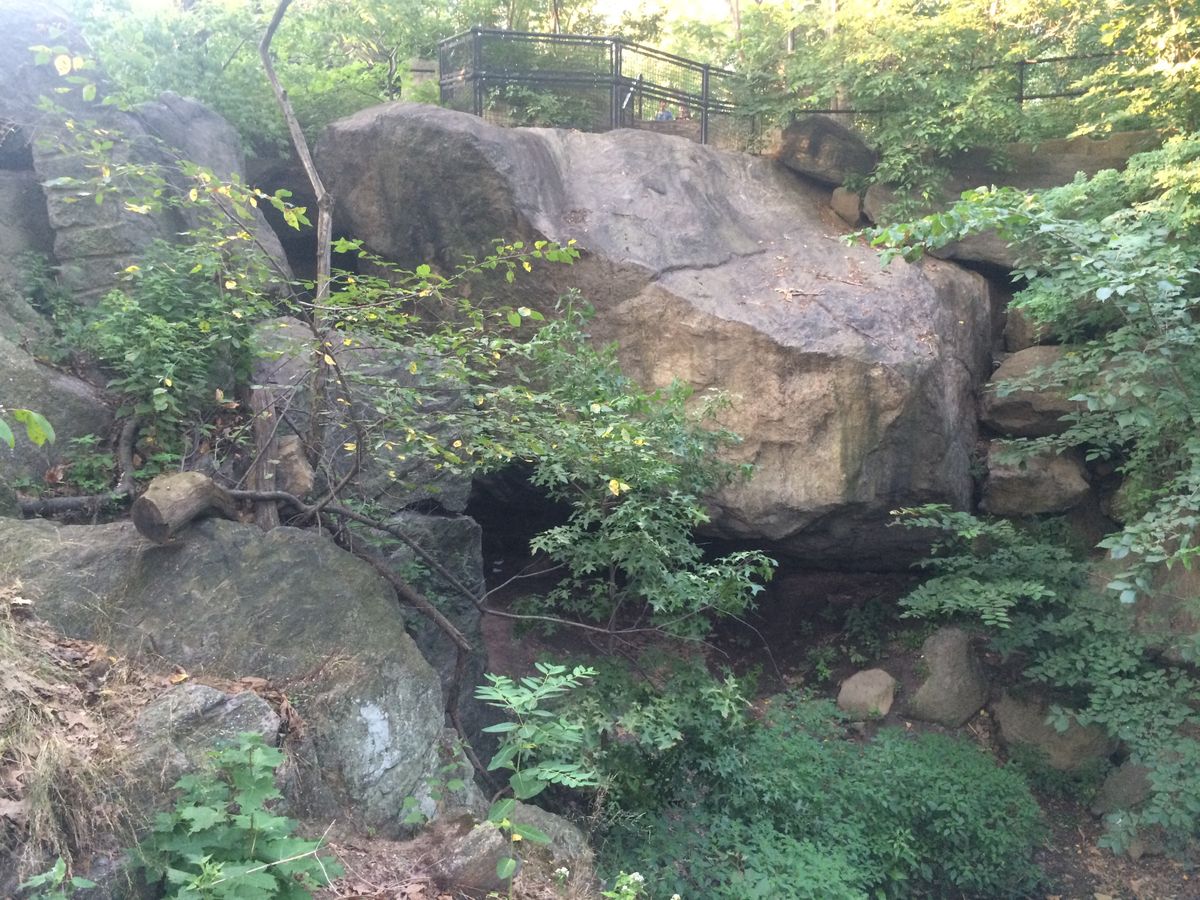

While the cavity was certainly an interesting find, it didn't quite fit the look that Olmsted and Vaux were going for, nor was it easily accessible from the elevated lake-side trails. To solve the first problem, several large rocks were set on top of the eastern wall with more stones set into the hill beside the north exit, giving the impression that they had slid down naturally.

As for accessibility, at the southern exit, by the Lake, rough stones were laid out to form a narrow staircase leading from the lake-side path down into the cave, with a border of larger stones hiding the stairs from view except from above.

The cave was a popular attraction in the Park, with one early guidebook calling it “a great attraction to boys and girls, and hardly less to many children of a larger growth.” Later in its life it would become known as the 'Indian Cave', supposedly because the floor showed evidence of early Native American inhabitants, though evidence of this is hard to find. Early sources refer to it simply as “the cave” or “the Ramble Cave”.

Sadly, it was also a popular spot for trouble. In 1904 a man was found near the steps, shot in the chest, supposedly the victim of a suicide attempt (the man, Samuel L. Dana, would recover, but the incident and its mysterious aftermath would set off a media frenzy). In October 1929, the Times reported that 335 men had been arrested in the Park just that year for what they generously termed “annoying women”, with the Ramble Cave held out as a particularly popular spot. Sometime in the 1930s the Cave was sealed off. The entrance by the lake was simply bricked up while the opening by the Ramble Arch was more elaborately sealed and covered over with dirt to make it appear as just another hillside in the Ramble.

The steps by the Lake are still there, however. Unless you know of their existence they, and the Cave, are the easiest things in the world to walk past, blissfully unaware of this once lovely feature of a young Central Park.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

On the western side of the Ramble, just below the Ramble Arch. The stairs are on the west side of the second small bay at the northwest of The Lake.

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

October 2, 2015

Sources

- Parsons, S. "The Cave in Central Park Ramble." The Literary News, 1891, 164-165.

- A Description of the New York Central Park (pp. 116-118). (1869). New York City, NY: F.J. Huntington and Co.

- Shot at Lake, Keeps Identity Secret. (1904, July 30). The New York Times, p. 12.

- 335 Seized as Annoyers. (1929, October 7). The New York Times, p. 16.