About

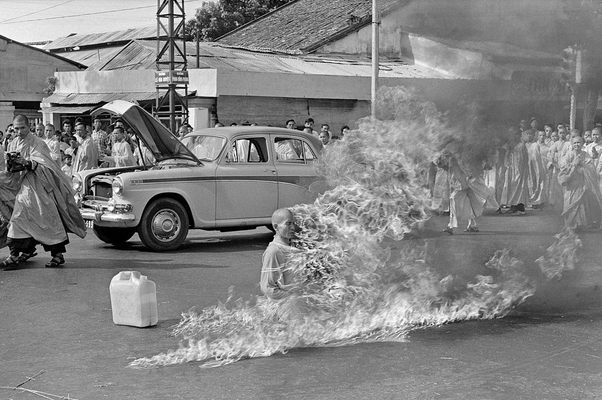

On June 11, 1963, Thích Quảng Đức rode to Saigon from the war-torn city of Huế in an Austin Westminster. He stepped out of the baby blue automobile onto a busy intersection and sat calmly in the lotus position while a colleague poured gasoline from a five-gallon container over his head.

Holding onto a string of prayer beads, the Buddhist monk spoke the words “Nam mô A Di Đà Phật” (“Homage to Amitābha Buddha"), struck a match, and placed it against his fuel-soaked robe.

In the 1950s, South Vietnam had become increasingly hostile towards its Buddhist citizenry. Buddhists made up an estimated 70 percent to 90 percent of the population, but the country’s first president, Ngô Đình Diệm, represented the Catholic minority. He took office in 1955 and enacted discriminatory policies that favored Catholics and neglected Buddhists for public service roles, military promotions, land allocation, and business arrangements. Despite an overwhelming majority of Buddhist citizens, the Roman Catholic Church was the largest landowner in Vietnam at the time.

In 1959, a ban on flying the Buddhist flag on the birthday of Gautama Buddha exacerbated the public discontent, and people took to the streets in protest. Government forces fired on the crowd and killed nine people. Diệm refused to accept responsibility, and outrage and consequential protests increased in the following years.

On June 11, 1963, Thích Quảng Đức, surrounded by a circle of protesters, burned himself to death. He described his intentions in a final note: “I respectfully plead to President Ngô Đình Diệm to take a mind of compassion towards the people of the nation and implement religious equality to maintain the strength of the homeland eternally.”

In 2010, a memorial, displaying the monk wreathed in flames, was installed on the very corner where he died a half century before (now Nguyễn Đình Chiểu and Cach Mạng Thang Tam streets). Prior to the statue, which sits in front of a bas-relief depicting the powerful action, American journalist Malcolm Browne’s photographs were the most accessible reminders of the event. He described the moment in a 1995 interview with the BBC: “I just kept shooting and shooting and shooting. And that protected me from the horror of the thing.”

Related Tags

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

January 2, 2018