About

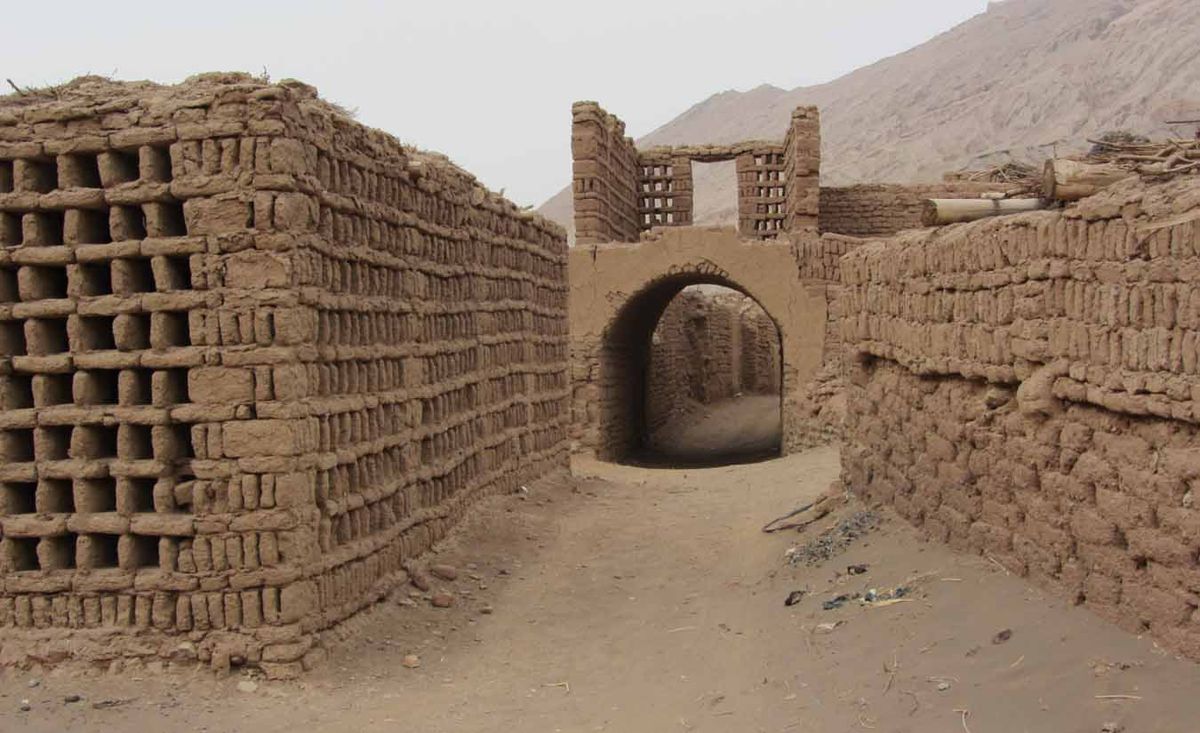

Set in the northernmost reaches of the Taklimakan Desert, this oasis-village is an often hostile place to inhabit. Winters here are arid and cold, while the summer months bring an unforgiving, scorching heat. In the short spring and autumn seasons, sporadic spells of bearable weather offer brief bits of respite. Yet despite the harsh environment, a culture rich with fascinating architecture and agriculture continues to thrive.

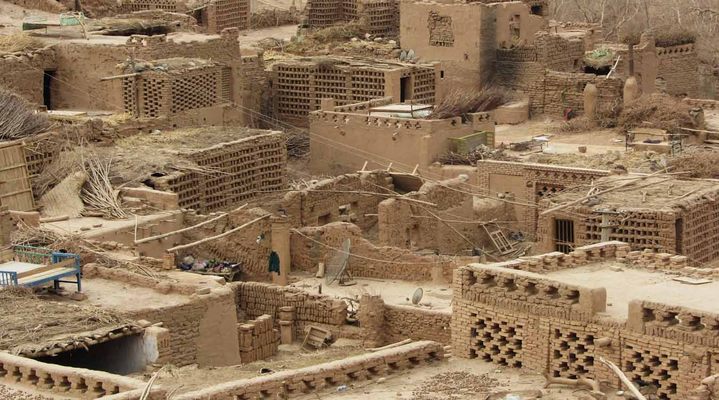

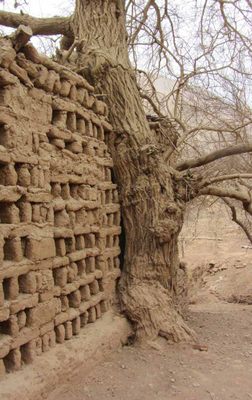

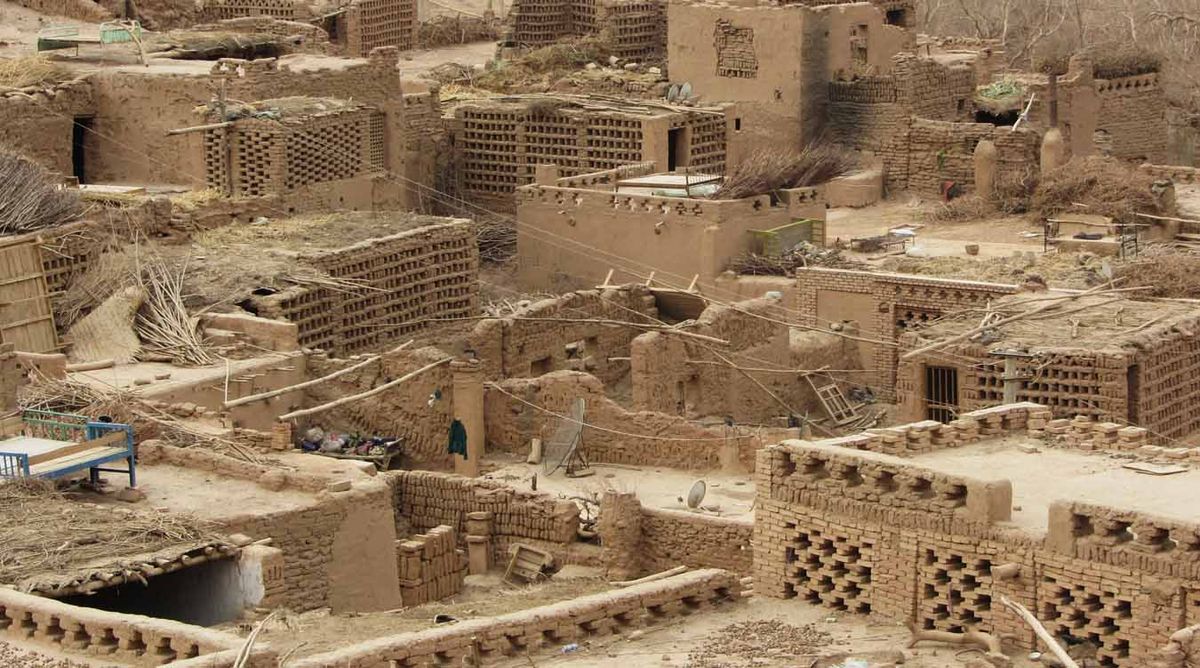

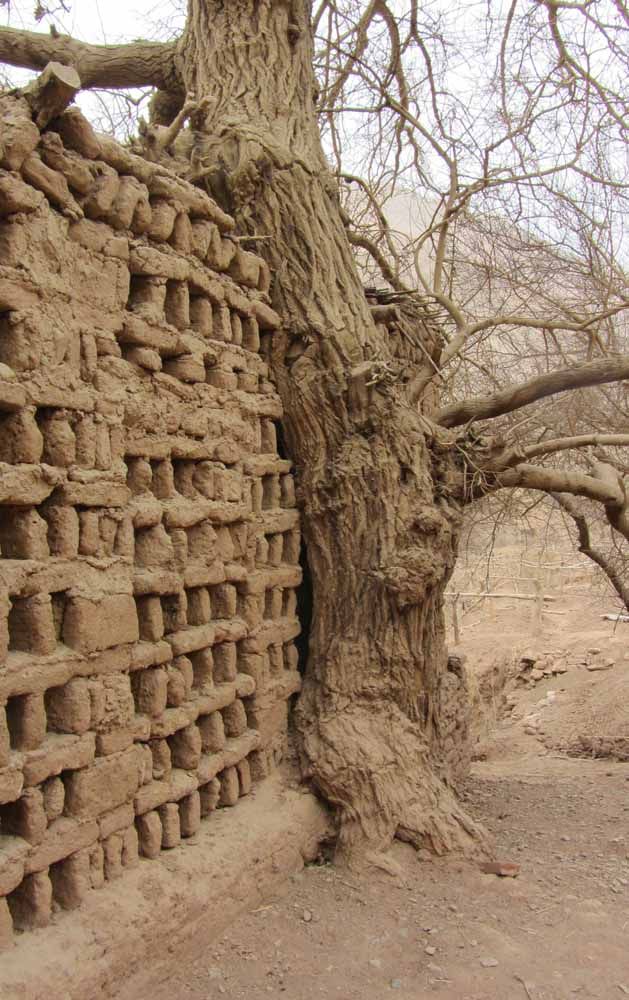

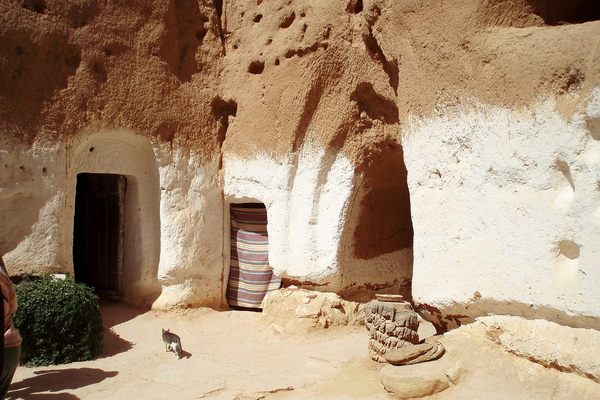

The village is set against the backdrop of the Flaming Mountains, named after the fiery tinge their sandstone gullies and trenches get at dawn and dusk. The mud-brick buildings of Tuyoq are fine examples of centuries-old (and perhaps millennia-old) Uyghur architecture. The gently rounded corners of the buildings blend in perfectly with their surroundings, making it difficult to tell where the soil ends and a dwelling begins.

The boundaries of the village are equally porous, as the buildings’ backyards turn into vineyards, which encircle Tuyoq and cover the vast majority of the valley. An ingenious underground irrigation method called karez (also called qanat) enables the people from Tuyoq to cultivate an otherwise arid and barren land. The network of gently sloping underground canals lets the locals produce manaizi grapes, which are famous for being sweet and seedless.

On the outskirts of Tuyoq is the Hojamu Tomb, which marks the site where the first Uyghur to convert to Islam is said to be buried. This tomb is so revered by the native Uyghurs (a Caucasoid and East Asian ethnic minority in East and Central Eurasia) that it has been a pilgrimage site for centuries. Unsurprisingly, the cemetery is in tune with the village, displaying above-ground caskets embellished with decorations made of mud.

Related Tags

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

March 5, 2018