About

During the Great Depression, the U.S. Department of Agriculture tried to help struggling rural communities by championing the diffusion of cheap and durable “Pisé de Terre” construction techniques. The future lay in the ancient ways: rammed earth homes, the quality of which they promised was “in some respects superior to frame and masonry,” and at a fraction of the cost. Other backers called the building technique a “revelation for the farmer or settler” that “leaves all the benefit and profit to the Self-Builder.”

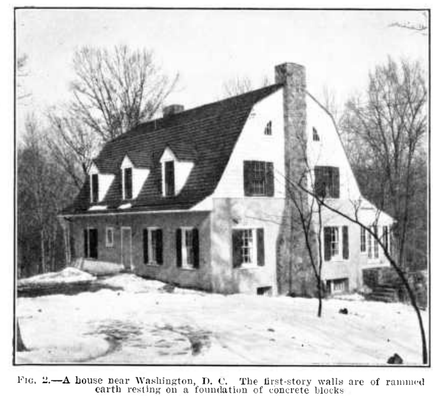

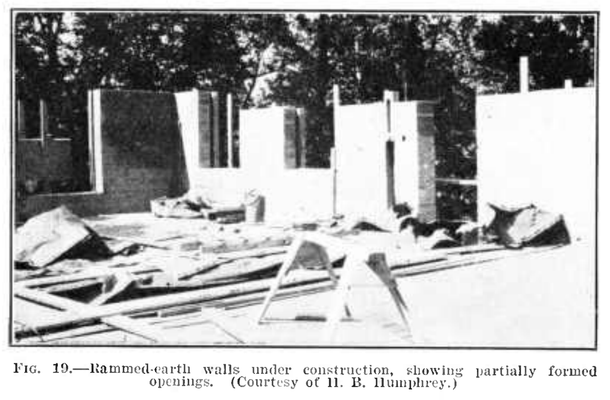

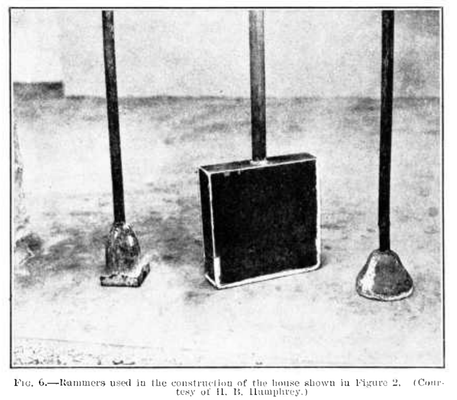

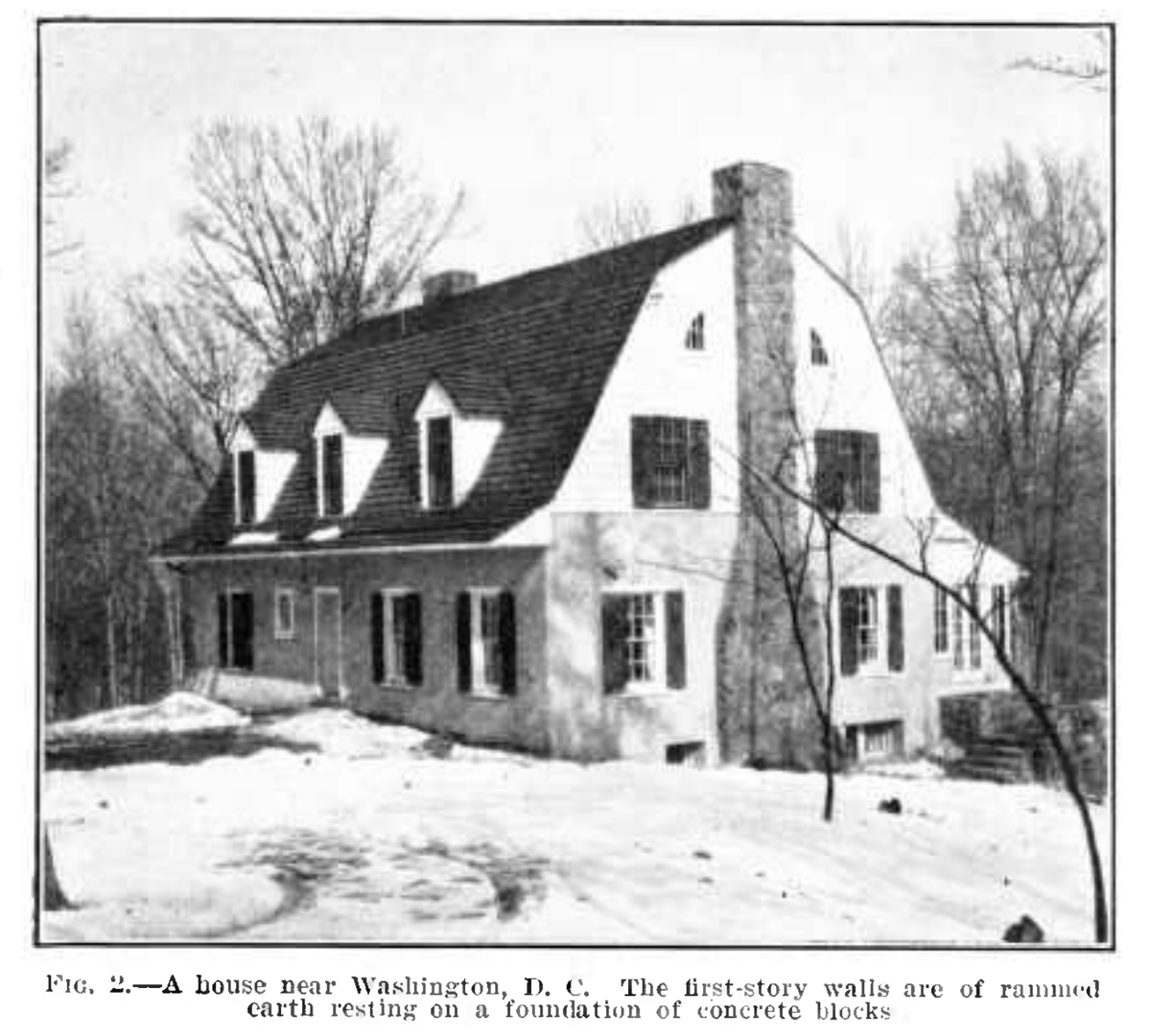

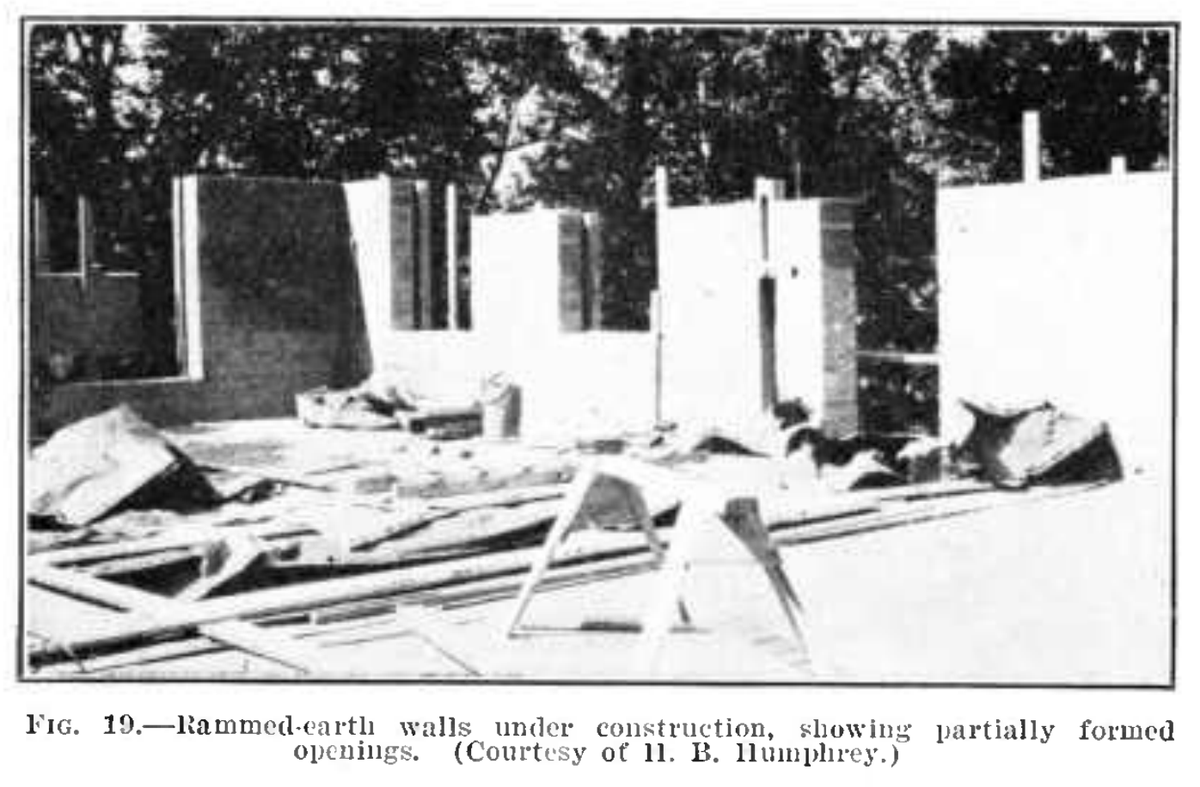

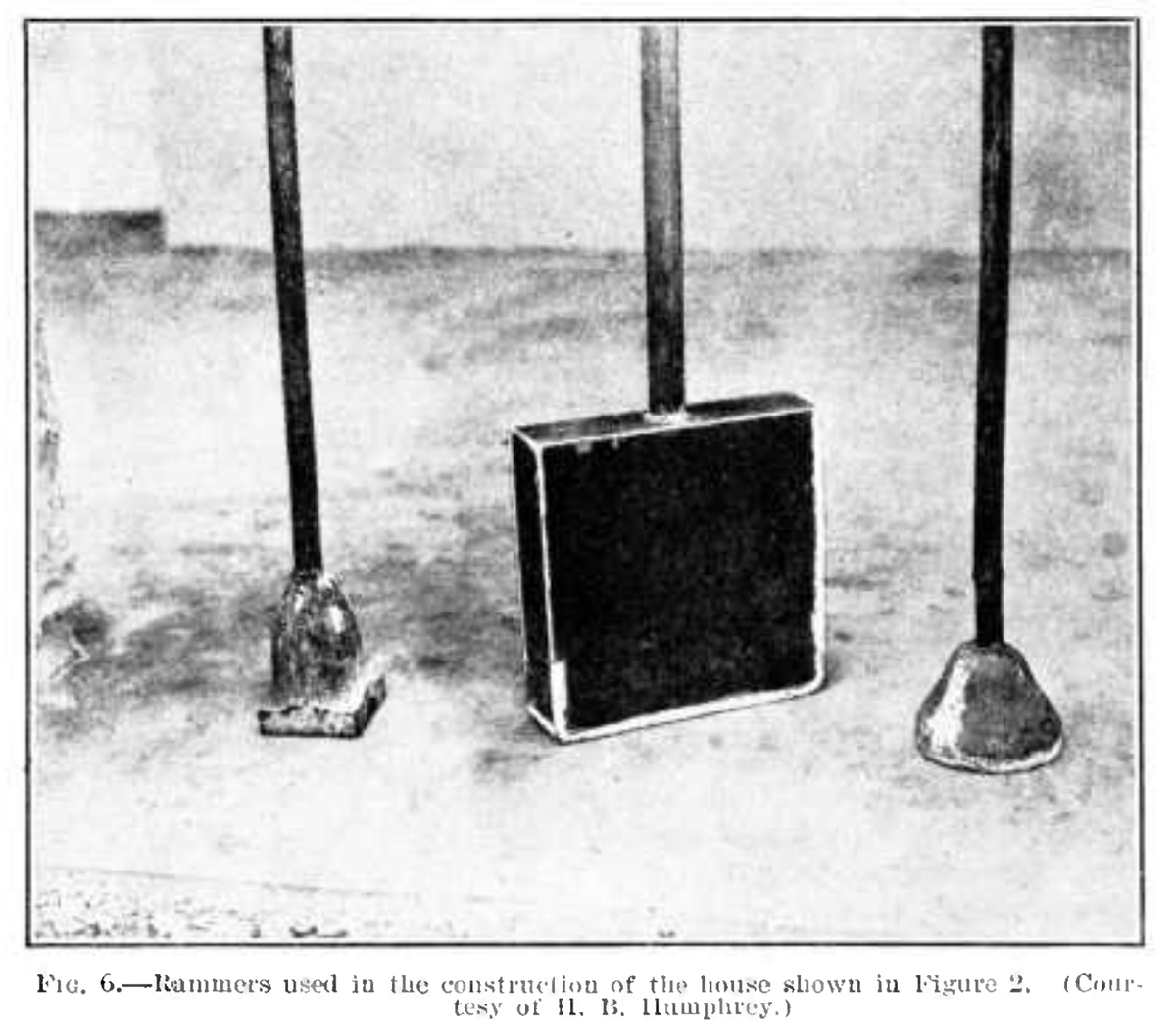

To test the idea out, USDA employee Harry Humphrey built a pilot model out in then-rural Cabin John, Maryland. The construction process was documented with technical specifications and in photographs that were sent out across the country in the Farmers Bulletin issue number 1500.

The pilot model had a concrete foundation (“to prevent moisture from rising”), 18-inch thick walls formed by tightly compressing clay, sand and gravel within temporary wooden forms, and a plaster exterior coating. Even the roof came out of the ground: 13 tons of baked clay tiles hung on a gambrel-shaped frame.

The house’s solid earth walls were built with internal conduits for electrical wiring, but nothing by way of air conditioning was needed because of the structure’s natural insulation from the weather. As of an October, 1976 Maryland historical report, this design remained fundamentally unaltered, and that likely remains the case to this day.

USDA saw rammed earth homes as an all-American silver bullet for cash-strapped Dust Bowl farmers. Unlike other construction materials, dirt is abundant even in the most remote homestead. And “self building” had a nice touch of the individualism that had carried settlers west in the first place. “The services of skilled artisans are not required, because pisé work presents so little difficulty that it can be done by anyone without previous experience who will exercise care in a few particulars.”

There are few extant signs of it today, but Pisé de Terre actually did gain some traction in the Midwest during the Great Depression, before fading in the post-World War II Levittown building revolution. The USDA pilot model stands today as a monument to the Department of Agriculture's unbuilt dirt-walled utopia. The Maryland Historical Trust notes that other than the fact that the original garage “has eroded away,” the rest of the structure seems to be going strong at 91 years old.

One final footnote worth mentioning is that future-Vice President Hubert Humphrey lived in the attic at age 24 when visiting Washington. The Maryland Historical Trust notes that while in town “Hubert visited the Capitol, witnessed Senate debates and began discussing politics with his uncle in the earthen house … Hubert wrote to his fiancee from his room under the tile roof, ‘if you and I just apply ourselves and work for bigger things, we can live here in Washington - I set my aim at Congress."

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

The pilot model house is a private residence.

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

October 3, 2017