About

On a balmy Thracian Sunday some 1,100 years ago, during a liturgy given in the massive basilica of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, possibly during the solemn, laborious prayer of the Anaphora, a bored soldier carved his name into the white marble parapet that surrounds the balcony of the church's upper gallery.

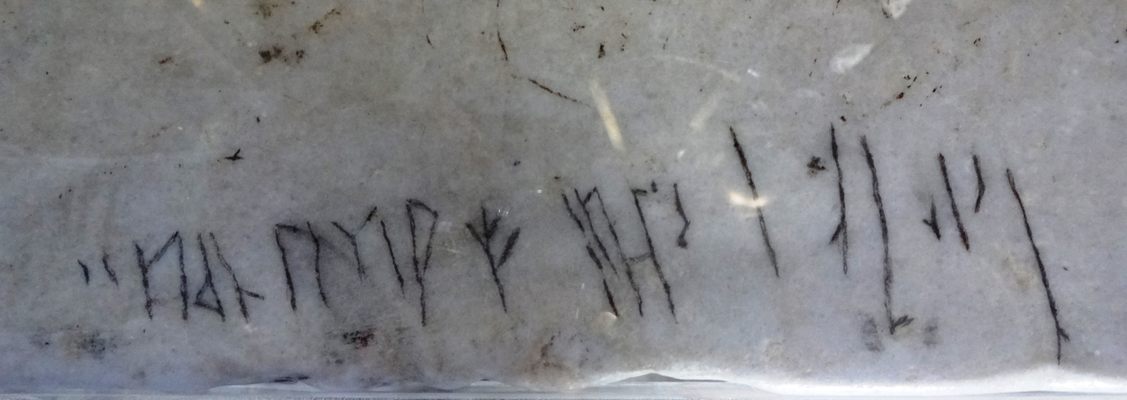

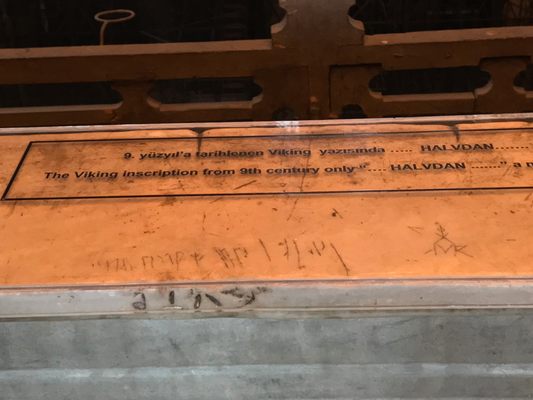

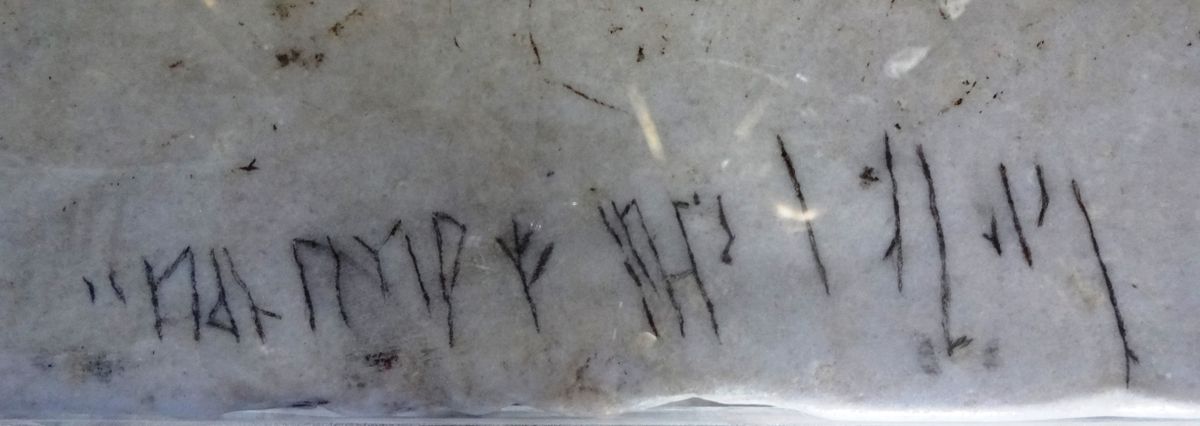

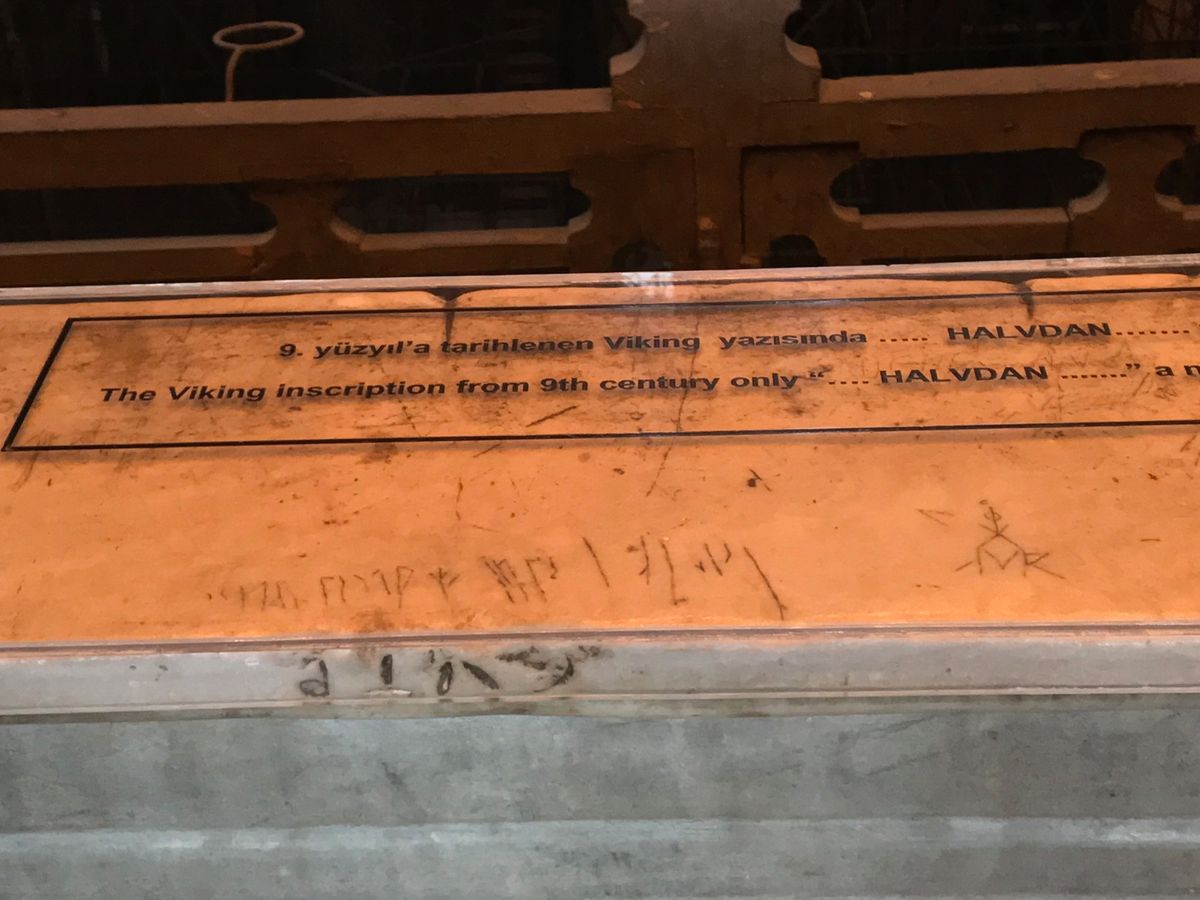

The letters he carved, however, weren't Greek; this wasn't a native warrior, but a Viking mercenary from the Scandinavian lands of the north. His runic inscription is still visible today. They read, approximately, "Halfdan carved these runes," or "Halfdan was here," a familiar sentiment shared by crude etchings across the millennia. A transparent plastic slab protects the inscription, which can be found in the gallery on the second floor of the basilica.

The Vikings who came to Constantinople to seek glory and occasionally great wealth were known as the Varangian Guard, after the Greek word for Viking or Norseman. The tradition of their service dates to the 9th century, when the Kievan Rus and the Byzantine Empire settled a peace treaty that allowed for some Rus warriors to join the empire's army.

Later Varangians included Harald Hardrada, who fought with the Byzantines against the muslims in Sicily before becoming King of Norway, as well as many 11th-century Anglo-Saxons ironically exiled from Britain by another group of Norsemen, the Normans.

The Varangians were prized not just for their massive size and handiness with an axe, but for their loyalty, as they had been steeped in an oath-driven warrior culture that prized fealty to one's lord. Also, having no local connections, the Viking mercenaries couldn't be suspected of conspiracy with the Emperor's enemies, who more often than not were located within the treacherous court of Constantinople rather than outside its walls.

Related Tags

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

May 15, 2018