About

Outside of Germany’s Ruhr Valley, history has largely forgotten the name Krupp, but just a generation ago it was an internationally recognizable byword for immense industry, and destructive weaponry. Successive generations of the Krupp family transformed Prussia into an industrial giant and served as the fatherland’s chief weapon smith in three major wars.

In 1870, family scion Alfred Krupp, the so-called Kanonenkonig or "Cannon King," set about constructing a lavish castle to house future generations of his family. The result was Villa Hugel, which still commands the twisting banks of the Ruhr, south of Essen to this day.

Like many of the industrialists who clawed their way to the top of the Gilded Age, Alfred was a shrewd businessman but also a bizarre eccentric. His two obsessions (efficiency and vertical integration) were joined with a slew of anxieties: hypochondria, insomnia, and a phobias of everything from fire to suffocation from his own bodily gases.

One can find hints of these personality quirks in the physical makeup of Villa Hugel, which is the architectural personification of Herr Krupp. William Manchester’s exhaustive chronicle of the family, The Arms of Krupp, notes that the madness began when “Alfred Krupp had reviewed the talents of all the leading architects on the continent, and decided the most highly qualified was Alfred Krupp.” While unquestionably a master weapon maker, the man had little skill when it came to architecture.

Krupp selected the location by having his employees (known for generations as kruppaianer) build a large wooden tower with wheels at the base that allowed him to see above the tree line. Alfred clambered to the top with a spyglass and shouted down instructions to lug the edifice this way and that until he found the best spot.

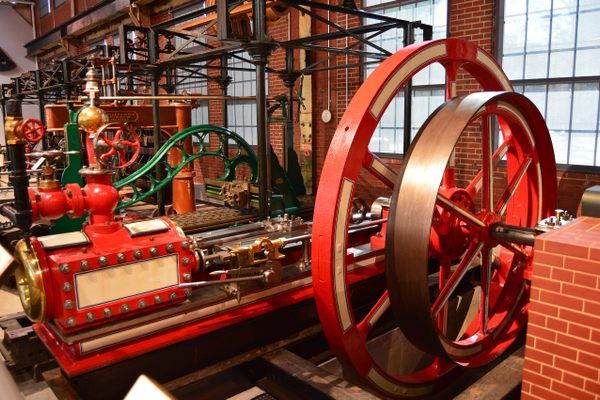

With the location in set, all attention now turned to building materials and designs. The three story building was to be supported with cast steel “kruppstahl” Alfred told the engineers, and clad with imported French limestone. Wooden beams or paneling were out of the question—imagine of the fire risk! Manchester further notes that “gas mains were unthinkable,” winter temperatures be damned. The resulting heating and ventilation issue might have been lessened, save for Alfred’s order that every window in the house be permanently sealed (drafts of air cause pneumonia, he believed.)

Construction and later occupancy of Villa Hugel were beset by problems. Within months of laying the cornerstone, the Franco-Prussian War erupted and the imported stone supply was in jeopardy. Alfred demanded that the French quarries continue their work, and astoundingly they complied, exporting their materials to Essen via neutral countries throughout the war (which they quickly lost in the face of Prussia's brutally effective Krupp artillery).

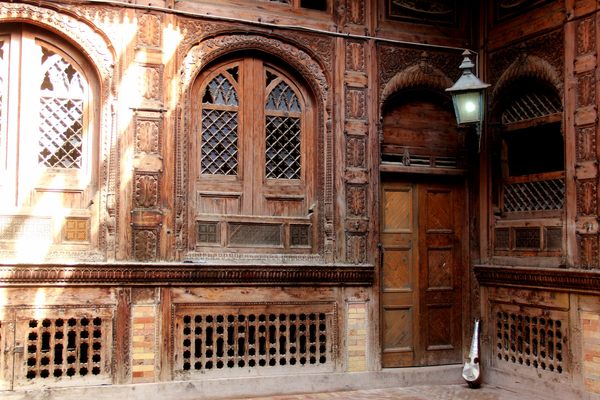

As the walls of Villa Hugel rose the interior layout of the house revealed itself to be an irregular network of grand double story halls, salon-like art galleries and dark passageways. Perhaps most bizarre of all, Alfred’s specially designed third-floor study was located over the stables so that the smell of horse manure could waft up through vents in the floors and lubricate his imagination. He viewed this as a feature and not a bug.

Problems continued to rear their head years after the palatial house had been completed. Save for the manure-smelling study, nothing seemed to work as intended. The Krupp-designed heating system was ineffective during the winter, and in the summer the metal roof cooked the house like a crockpot. By the time of Alfred’s death in 1887 he had become convinced that Villa Hugel had a personality, and that it hated him. His children felt much the same way and called it “the tomb.” The one thing that everyone did comment on were the lovely lawns, twice the size of New York's Central Park.

Regardless of their feelings towards the building, Villa Hugel continued to be the official residence for successive generations of the Krupp dynasty until World War II put an end to de Konzern once and for all. Alfred's descendant Alfried Krupp had gotten in deep with the Nazis and when Patton’s army captured Essen in 1945 he was arrested as a war criminal. Charges included the use of foreign slave labor in his weapon shops and plundering.

British bureaucrats then occupied the house for a number of years until matriarch Bertha Krupp demanded that they return the property. Alfried Krupp served just two years in prison for his crimes, controversially receiving an amnesty from the Americans, but he never again called Villa Hugel home.

Today the house operates as a museum and a monument to the family that the Washington Post typified as seeing themselves “slightly above royalty and slightly below deity.”

Related Tags

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

July 13, 2017