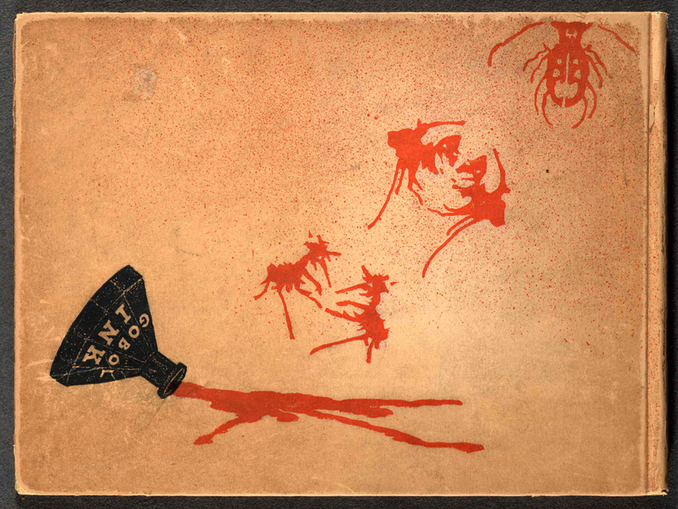

Gobolinks, Blottentots, and the Eerie Beauty of Victorian Inkblots

Before the Rorschach Test, klecksography was seen as poetic inspiration.

Today inkblots are almost universally seen as psychological diagnostic tools. But before the “Rorschach Test” became a household term, there was the Victorian game of Gobolinks, which used inkblots to inspire eerily imaginative poems based on the random chaos of ink dripped on paper.

Technically known as klecksography, inkblot art got its start back in the 1700s. German poet and physician Justinus Kerner is generally credited with innovating the form after he began accidentally dropping ink blots on his papers as his eyesight failed. Seeing them as more than just sloppy mistakes, he would fold the paper and create a single mirrored form, which he would then interpret and add to, ending up with illustrations he would then pair with his poetry. Kerner’s artistic work would eventually be published in 1890 in the German language book, Klecksographien.

“The allure for me is that this is a pre-verbal language,” says Tyler Kline, a visual artist who has been incorporating klecksography into his own work for over a decade. “With a lifetime of investigation and study, codes and cyphers can be developed. The image will be read on multiple levels.” The same evocative ambiguity that make inkblots perfect for psychological readings, make them terrific inspiration for artists of any age.

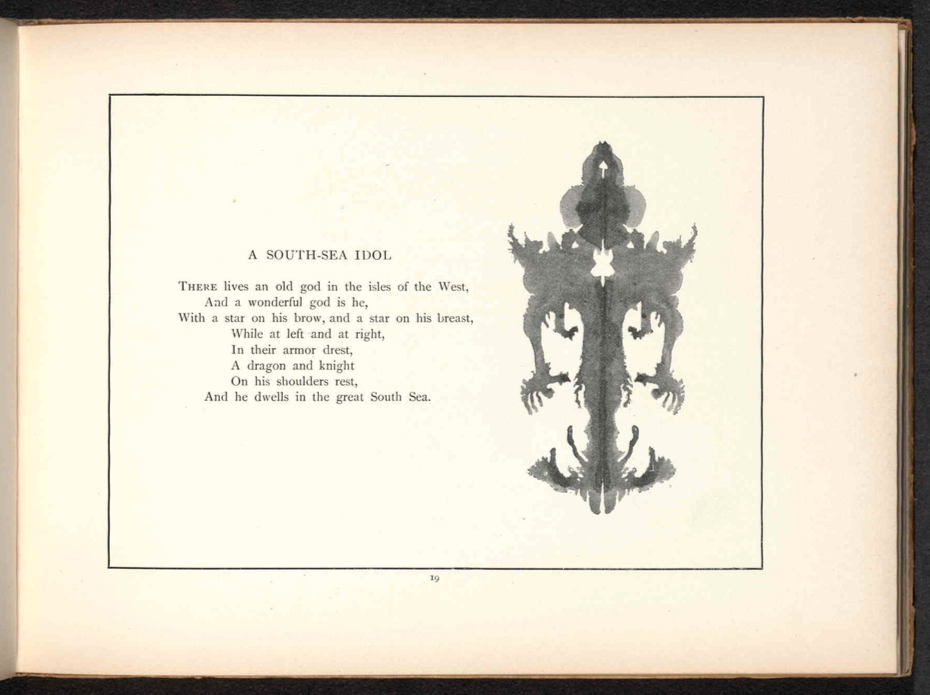

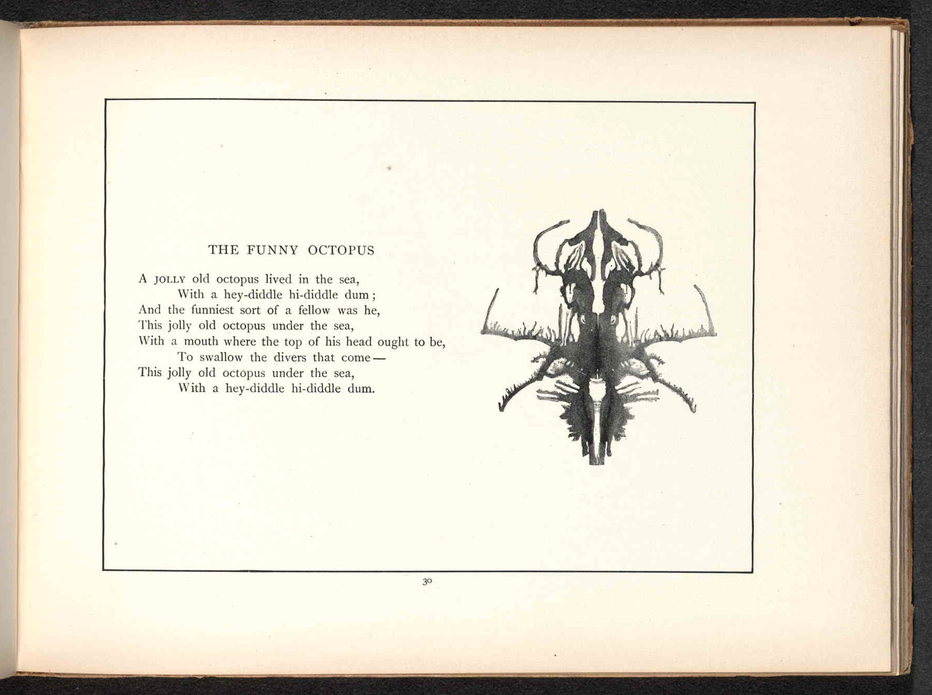

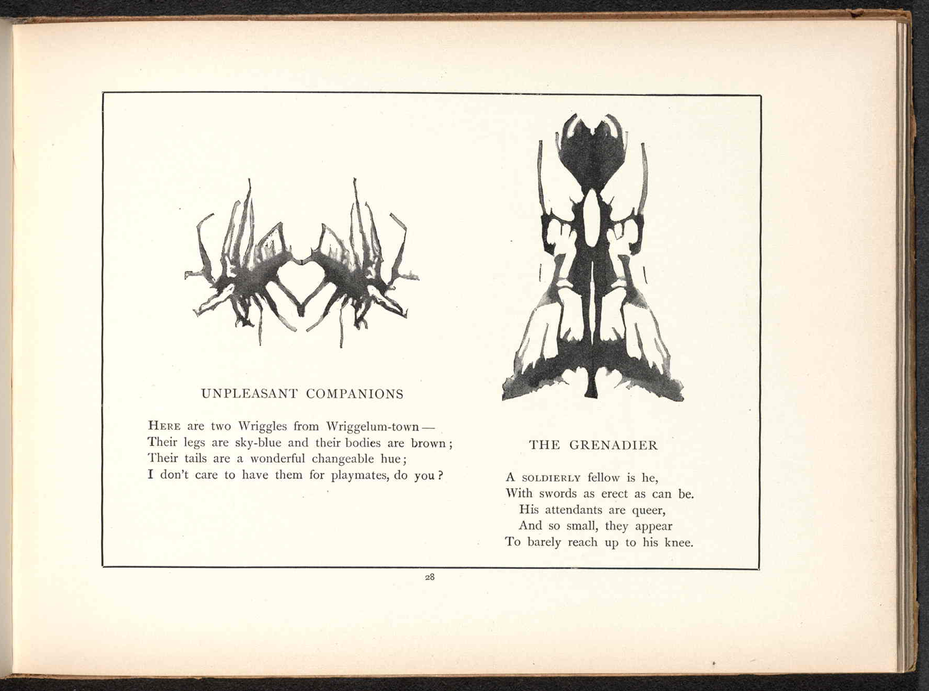

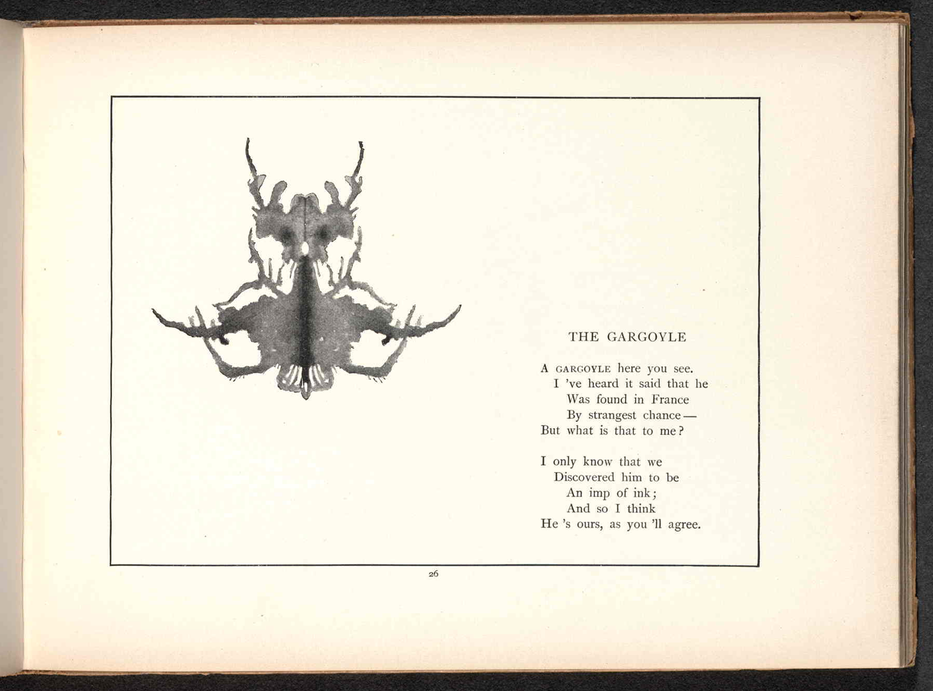

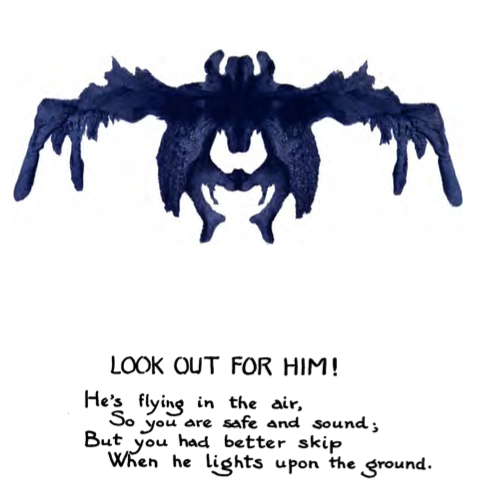

Undoubtedly inspired by Kerner’s work, released just a few years earlier, two American authors, Ruth McEnery Stuart and Albert Bigelow Paine took his process a step further, when they released their terrifically titled book, Gobolinks, or Shadow Pictures, in 1896. Stuart and Paine envisioned the creation of inkblot art as an act of chaos and imagination. As defined in the book, a “gobolink” is a “veritable goblin of the ink-bottle,” The idea being that the blobby splotches of spilt ink create unique creatures free from the creator’s influence, but still defined by their interpretation.

“One of the characteristics of inkblots is their dynamic and organic nature,” says Kline. “The technique of creating inkblots is one where the ink records a physical action. What was transient now has stasis.”

The book also outlines a set of rules that gamifies klecksography. The game of Gobolinks asks players to create ink blots, write a rhyme based on the image, then choose judges among the players to assess which of the blobs are the best, and which is the “booby.” The authors also suggest that people dress up for a Gobolinks party, wearing outfits that are the same on one side as they are on the other, just like an inkblot. As they say, “No game could be more productive of amusement than Gobolink.”

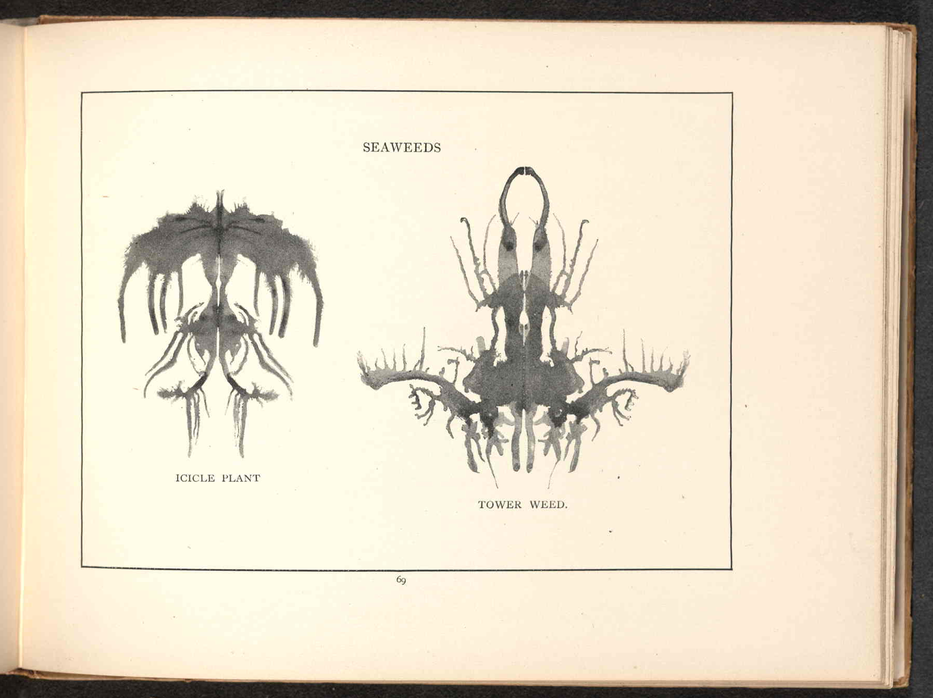

As they are presented, the rules are overly complicated, and seem pretty judgmental by modern standards, but the resulting artworks are nonetheless remarkable. Over 84 gobolinks are presented in the book, most accompanied by poems, while a few are simply grouped by their general shapes, into groups like “Seaweeds.” Yet they all share the same slightly creepy form and symmetry for which klecksography is known.

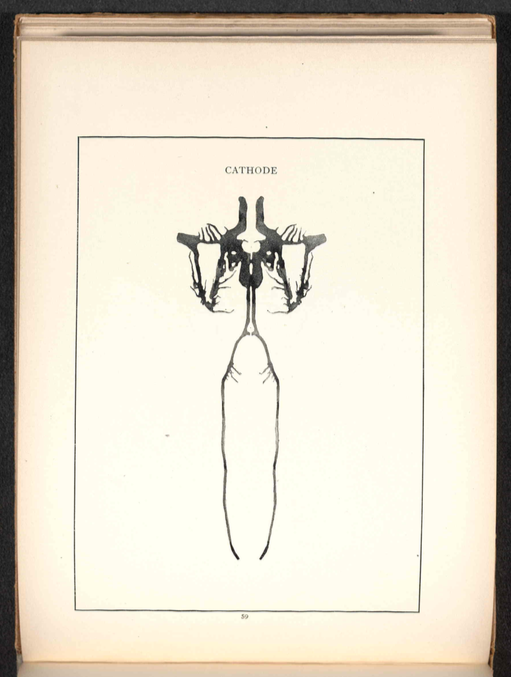

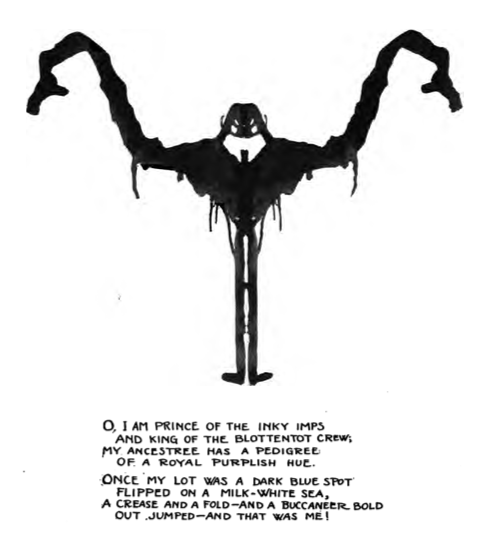

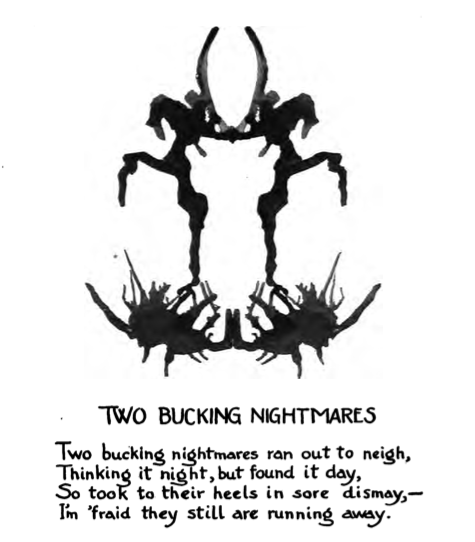

While Gobolinks is the gold standard for whimsical turn-of-the-century klecksography, it was not the only book of its kind. In 1907, a short, but equally delightfully named book called The Blottentots was released, containing another set of ghostly inkblots alongside poetry. While clearly derivative of Gobolinks, the Blottentots were just as unique and charming, but also seemed to embrace the inherently shadowy, otherworldly look of inkblot creations.

In 1921, Hermann Rorschach published Psychodiagnostik, which became the clinical bedrock on which the psychological inkblot test would be based. Klecksography then became more commonly associated with psychology than with poetic exploration. However, using inkblots as art is far from dead. There are still artists like Kline who are still keeping it alive, and even evolving. “My favorite technique is using multiple folds to create a rhythm of symmetry,” he says. “I am looking to unlock the hidden asymmetry of klecksographs.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook