The Hunt for Ukraine’s Toppled Lenin Statues

Photographing the hidden afterlives of Soviet monuments.

On the night of December 8, 2013, demonstrators were gathered in Kyiv’s Bessarabska Square. For two weeks there had been protests across Ukraine against President Viktor Yanukovych’s pro-Russian government, and on that wintery Sunday, some dissenters found a symbolic target for their frustration. Primarily aligned with the nationalist Svoboda party, the protestors tore down the 11-foot-tall statue of Vladimir Lenin that had loomed above the square since 1946, and battered it with sledgehammers.

The toppling of the Bessarabska Lenin led to a phenomenon that has become known as Leninopad, or “Leninfall”—the removal of Lenin statues from around Ukraine. Of course, it wasn’t the first time Soviet monuments had been brought low, as statues had been destroyed as early as 1990. But in the following months the intensity increased—so much so that in February 2014 alone, a total of 376 statues were torn down.

Ukrainians had a lot of statues to work with, but their efforts were diligent and comprehensive. In 1990, when Ukraine declared its independence from the Soviet Union, there were 5,500 Lenin statues around the country, more than in any other former Soviet republic. With the country’s 2015 decommunization laws, which outlawed communist symbols including statues, flags, and Soviet-era place names, there was a mandate to remove the last of the Lenin monuments. Today, none still stand. But they haven’t disappeared.

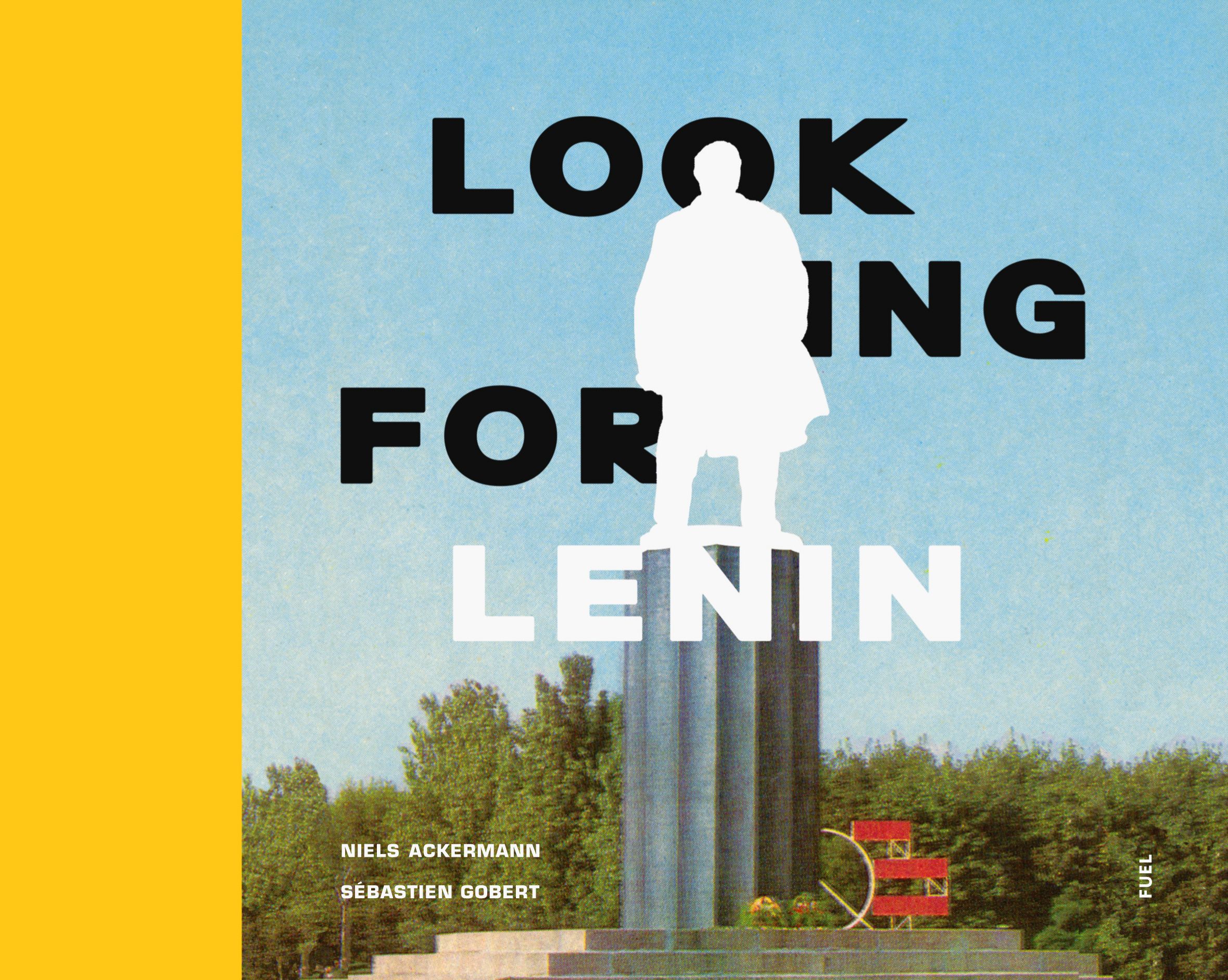

The afterlife of these statues is the subject of the new photobook from Fuel Publishing, Looking for Lenin. Photographer Niels Ackermann and journalist Sébastien Gobert started the project by searching for the remains of the Bessarabska Square Lenin, and they ended up photographing toppled Lenins across the country. Their goal was not just to see where the physical embodiments of the Soviet past had ended up, but also to discover how Ukrainians felt about the ongoing process of decommunization.

“We met scores of people who wanted to discuss the subject,” writes Gobert in the book. “The name ‘Lenin’ loosened tongues: for, against, indifferent, nostalgic, vindictive—everyone had an opinion about Dyadya Vova (Uncle Vlad).”

The Lenins that Ackermann and Gobert found—figures that had previously towered on plinths as a mark of Soviet authority—now fill car trunks, are hidden in the woods, or are stashed in cleaning rooms. Here is a selection of images of the physical and symbolic remains of Ukraine’s past.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook