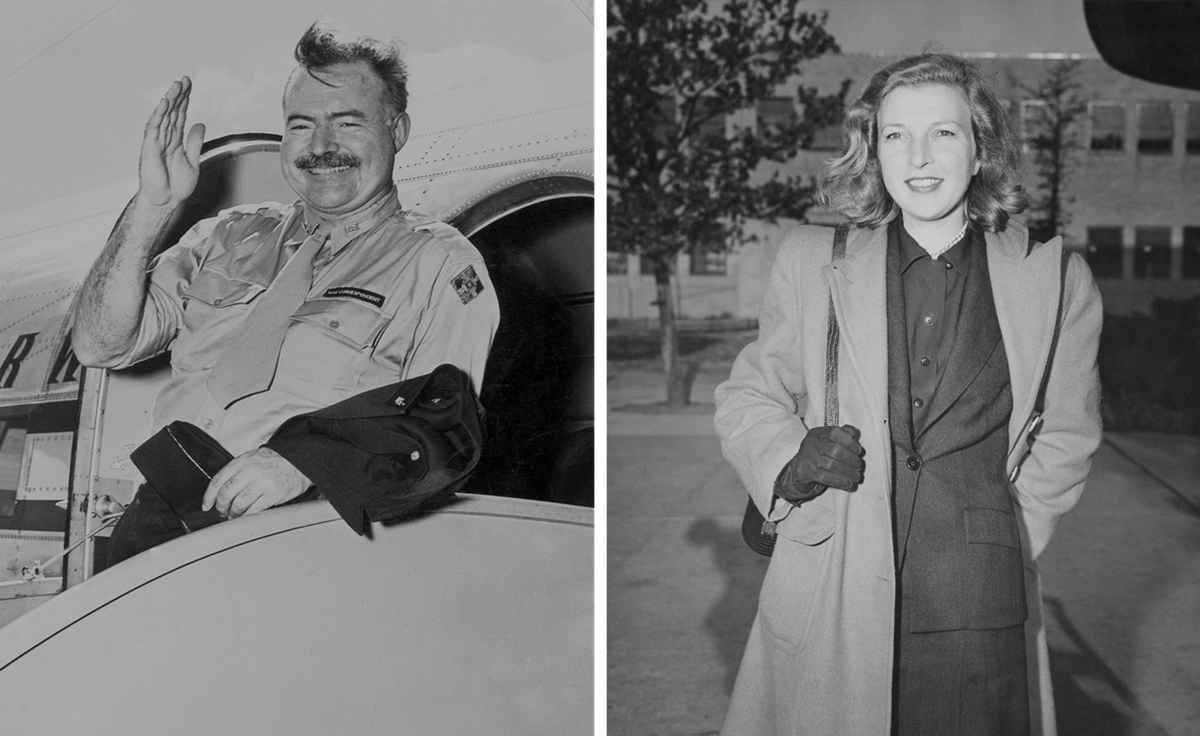

After Lovers Hemingway and Gellhorn Faced Off on D-Day, They Filed for Divorce

It turns out battling for journalistic scoops during wartime is not great for a marriage.

The American war correspondent, Martha Gellhorn, walked along a corridor at the London Clinic, a private hospital in central London, looking for her injured husband, Ernest Hemingway. Hemingway had been at a party the night before in Belgravia Square, the domain of London’s high society. His friend, the driver, was drunk, and crashed the car on their way back to the Dorchester hotel in the early hours of May 25, 1944.

Gellhorn heard about her husband’s accident on her journey down to the capital from Liverpool. She’d only just crossed the mine-strewn waters of the Atlantic from her home in Cuba, on a ship laden with dynamite, when she found out her husband had gashed his head quite badly.

She found Hemingway in bed, surrounded by empty whiskey bottles, and a crowd by his side in raptures. Their hoots of laughter filled his hospital room. Gellhorn offered her husband little sympathy. In fact, she was annoyed at him: Hemingway had decided to cover the ongoing war for Collier’s, the magazine she worked for.

Hemingway and Gellhorn’s marriage had broken down by then. They had fallen out of love since marrying four years earlier, in 1940, and now lived apart. A journalistic rivalry, however, still burned strong. The couple were in London to report on the pinnacle of the Second World War: the D-Day landings. Come June 6, 1944, when the allies reached Normandy, this rivalry would play out in spectacular fashion.

Gellhorn and Hemingway first met in 1936 at a bar called Sloppy Joe’s in Key West, Florida. Their relationship blossomed during their coverage of the civil war in Spain. Both were phenomenal writers, known for daring reportage from the battlefield. Their similarities made them natural allies, and passionate competitors, in journalism.

Gellhorn spent the end of 1943 and the beginning of the following year in Europe, reporting on the war from the United Kingdom and Holland. Gellhorn wrote for Collier’s and had been a loud advocate for American intervention into the war. She didn’t understand why her husband, the famed author and fellow war reporter, had not joined her in Europe, where all the excitement was.

Instead Hemingway, a man who often projected himself as a daring sportsman, decided to patrol the coast of Cuba, where he lived, in his 38-foot fishing boat. He was supposedly on the hunt for German U-Boats. He refitted the boat, called Pilar, with a radio to intercept U-boat communications and a machine gun. Hemingway even kept grenades on board.

Gellhorn traveled back to their home in Havana, the Finca Vigia, armed with a plan to convince Hemingway to join her in Europe. Gellhorn had negotiated a deal with author Roald Dahl, who worked for the British Royal Air Force at the time, for Hemingway to get a free seat on a plane to Europe if he wrote positively about the R.A.F. for an American publication. A spot on a transatlantic flight at the height of the war was a rarity, and someone as celebrated as Hemingway would have newspapers and magazines chomping at the bit to publish his stories.

He agreed, and to the dismay of Gellhorn, chose Collier’s to publish his war dispatches. Gellhorn was furious at the decision—she viewed it as a blatant attempt by Hemingway to steal her thunder, and column inches. Gellhorn was an admired writer in her own right; one of America’s first female war correspondents, as well as the author of several novels, short stories, and novellas.

But she couldn’t compete with the notoriety of her husband. So the two went to textual war, says Kate McLoughlin, author of Martha Gellhorn: The War Writer in the Field and in the Text, as they battled for scoops on the battlefields of Europe.

On June 6th, 1944, Ernest Hemingway sat shoulder to shoulder with Allied soldiers on a boat destined for the French coast. The Dorothea L. Dix struggled against heavy waves and as the vessel got closer to France, the sound of rattling machine-gun fire filled the sky.

Warships on either side of Hemingway’s 36-foot coffin-shaped boat launched shells towards the beach. The Germans fired back: “ahead of us, death was being issued in small, intimate, accurately administered packages,” wrote Hemingway.

As the coastline approached, Hemingway discussed the plans for landing with an officer. He wrote in his Collier’s piece that he had studied the relevant maps, and, amid the chaos of the approach to the beach and the bloodshed of the invasion, Hemingway told the officer that they were indeed headed in the right direction. It was clear from his account that Hemingway played dual roles as a journalist and a member of the invading force. That was the day, Hemingway wrote, “we took Fox Green beach.”

Meanwhile, Gellhorn had started the day in a dark room at the Ministry of Information in London. The British government would not allow her, a woman, anywhere near the frontline. Collier’s magazine held the same view. Her role would be to cover “the rear” and the women’s angle. Gellhorn, fueled by a competitive zeal not to be outdone by her rival and husband, and by her own fervent desire to cover the war, sped in a car towards the southern coast.

On the way, a policeman stopped her. She told him that she was going to report on the woman’s angle for Collier’s magazine. “No one gave a hoot about the women’s angle, it served like the perfect forged passport,” said Gellhorn during an interview later in life.

Gellhorn tricked an official into thinking she was a nurse and they let her onto a hospital ship bound for France. Once aboard, she found the nearest toilet and locked herself inside. Her ship crossed the English Channel and arrived in France on the morning of June 8, two days after the Normandy beach landings.

She was soon confronted with bloodshed and mayhem of the invasion, and recorded the misery in great detail. Gellhorn was not just an observer; she helped to stretcher wounded soldiers back to the ship. “We waded ashore, in water to our waists, having agreed that we would assemble the wounded from this area on board a beach LCT (Landing Craft Tank) and wait until the tide allowed the motor ambulance to come back and call for us,” wrote Gellhorn, in an article for Collier’s published in August 1944.

Gellhorn’s wariness about her husband swooping in to cover the war for the same publication were proven right, McLoughlin says, when Collier’s ended up giving Hemingway more prominence in the D-Day edition of the magazine

Collier’s magazine printed “Voyage to Victory By Ernest Hemingway” on the front cover of the July 22nd edition. Hemingway had five pages dedicated to his account of the D-Day landings. A large photo of him surrounded by soldiers accompanied the first page of the article. Meanwhile Gellhorn had a one-page piece on page 16 and no photograph.

Gellhorn’s story, “Over and back” was published without any direct reference to her relief effort on the Normandy beach. Instead the piece documented ancillary matters. Her own, very dramatic retelling of the scene from Normandy two days after the invasion was not published until August 5th. And, despite a rich and detailed account of the invasion, this piece made no reference to Gellhorn’s extraordinary backstory of hiding in a ship’s toilet to get there.

After covering the invasion and its aftermath, the couple followed different routes for much of the remainder of the war. Hemingway reported on the American advance to Paris, and Gellhorn wrote from the liberated Dachau concentration camp.

“We have all seen the dead like bundles lying on all the roads of half the earth, but nowhere was there anything like this,” she wrote from Dachau on June of 1945. “Nothing about war was ever as insanely wicked as these starved and outraged naked, nameless dead.”

Hemingway had a more swashbuckling style and preference for vivid descriptions of the action as it unfolded. Gellhorn’s focus was darker, and she paid more attention to the casualties of war. There was a final twist to their D-Day showdown, however. No one ever saw Hemingway get out of the landing craft, and, despite clearly implying that he went ashore from his D-Day report, some scholars believe he never actually made it onto the beach.

Gellhorn walked out on Hemingway at London’s Dorchester Hotel after an argument in 1945. After they divorced, she refused to allow anyone to mention his name in her presence, and her sense of injustice about being constantly identified by her five-year marriage to the famous author remained for the rest of her life. ”Why should I be a footnote to somebody else’s life?” she wondered. In her later writings, Martha Gellhorn referred to Ernest Hemingway only as “Unwilling Companion.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook