During WWII, ‘Rumor Clinics’ Were Set Up to Dispel Morale-Damaging Gossip

A network of “morale wardens” tracked down the latest scuttlebutt.

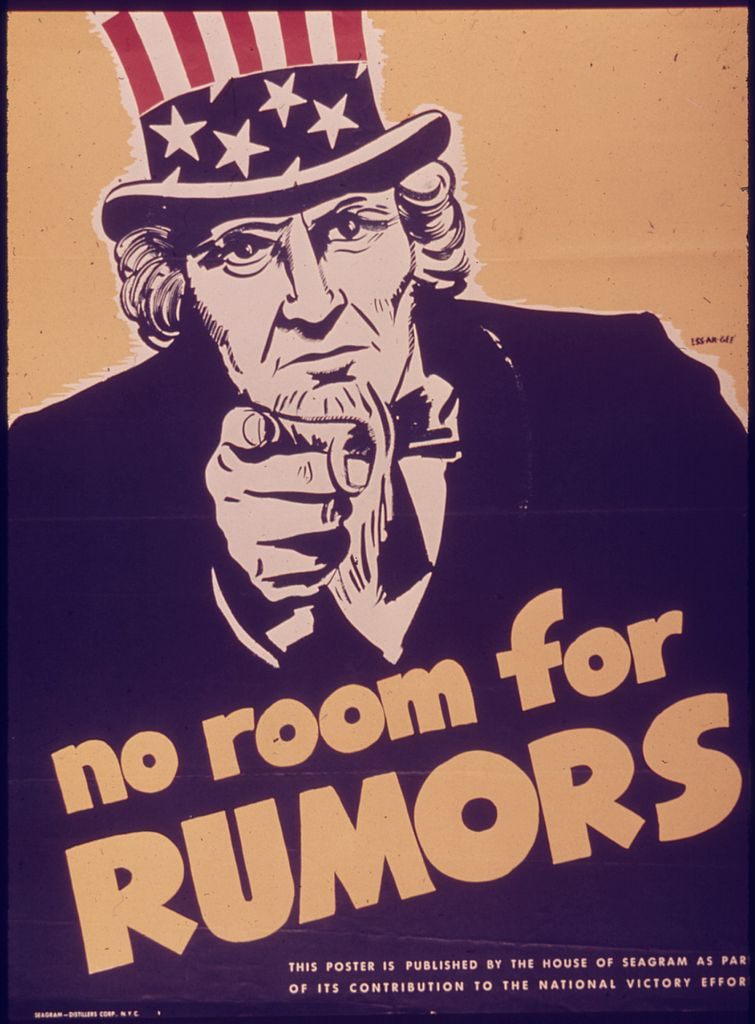

Rumors, like most forms of gossip, are usually rooted in half-truths and outright falsities. Yet, during World War II, these insatiable tidbits of hearsay threatened to undermine civilian morale and even cause unrest within the military community when they nearly spiraled out of control.

“Of all the virus that attack the vulnerable nerve tissues of a nation at war, rumor is the most malignant,” reported LIFE magazine in 1942. “Its most dangerous carriers are innocent folk who love to tell a tall tale.”

Rumors snowballed in pubs and on factory floors, and other places where chatter was high, despite the government urging Americans to “avoid loose talk.” The most common rumors attacked U.S. war efforts and involved so-called crimes committed by and against U.S. soldiers. Others were outrageous claims, gaslighting techniques and psychological warfare waged by Germany and the Axis powers, meant to cause doubt, panic, and fear among the American public.

For example:

No U.S. Navy vessels survived Pearl Harbor.

A mother in Minnesota received a box from Japan containing the eyes of her captured soldier son.

Men and women were being killed at shipbuilding corporations for supporting military efforts.

A bomb containing “bubonic plague germs” was dropped in Curry County, Oregon.

The WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service) were considered property of Army officers and the officers could do with them what they pleased.

The rumor mill churned.

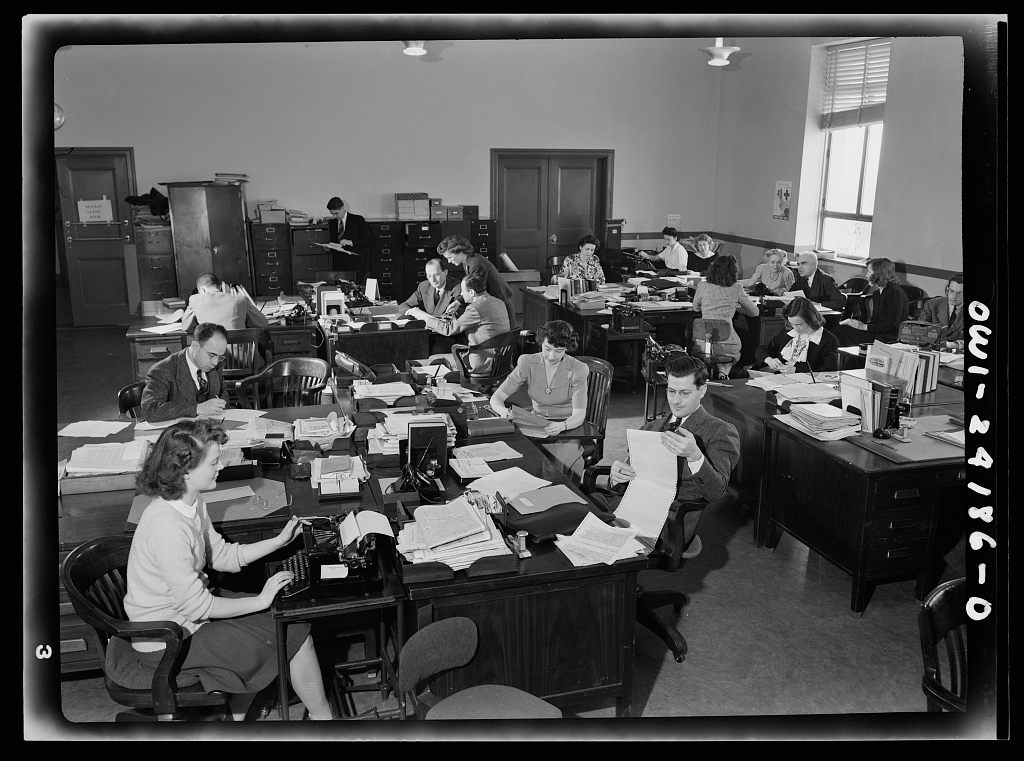

Recognizing the potential for widespread distrust and damage to civilian morale, President Franklin Roosevelt signed an executive order creating the Office of Wartime Information (OWI) on June 13, 1942. OWI consolidated several agencies, and was designed to be a central repository for overseeing and disseminating all wartime information that circulated in the United States. The office’s objectives were to subdue the falsehoods and promote only “positive” information on the progress of the war effort and activities of the U.S. government. Along with patriotic radio broadcasts and Voice of America, a government-funded news source that operated as radio broadcast during WWII, OWI’s grandiose plans included the “Rumor Project,” which was first proposed in January of 1942, before the establishment of OWI.

When Axis-inspired rumors became problematic, the Rumor Project was suggested as a way of informing and educating the American public on how to identify fact from fiction—real news from fake news, by today’s standards. The proposal for the project recommended that “Rumor Clinics” be instituted at colleges and universities across the United States, consisting of specialized groups of volunteer professors and students who researched well-known rumors and reported back to OWI.

Eight potential clinics were initially identified, including one in Boston to be run under the direction of psychologist Robert Knapp, an early researcher in the psychology of rumor. Twenty more clinics were proposed. But the program fledged and stalled under government bureaucracy. Officials were uncomfortable with social scientists having any level of information control, and social scientists could not work within the politics of the “establishment.”

The American public had also grown to mistrust the Roosevelt administration. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the government did not immediately provide details on the number dead and how the United States would respond. It took three weeks for them to release an official statement. The delay, combined with previous mishandling of public information related to the war, caused public confidence to drop to an all-time low and rumors to proliferate.

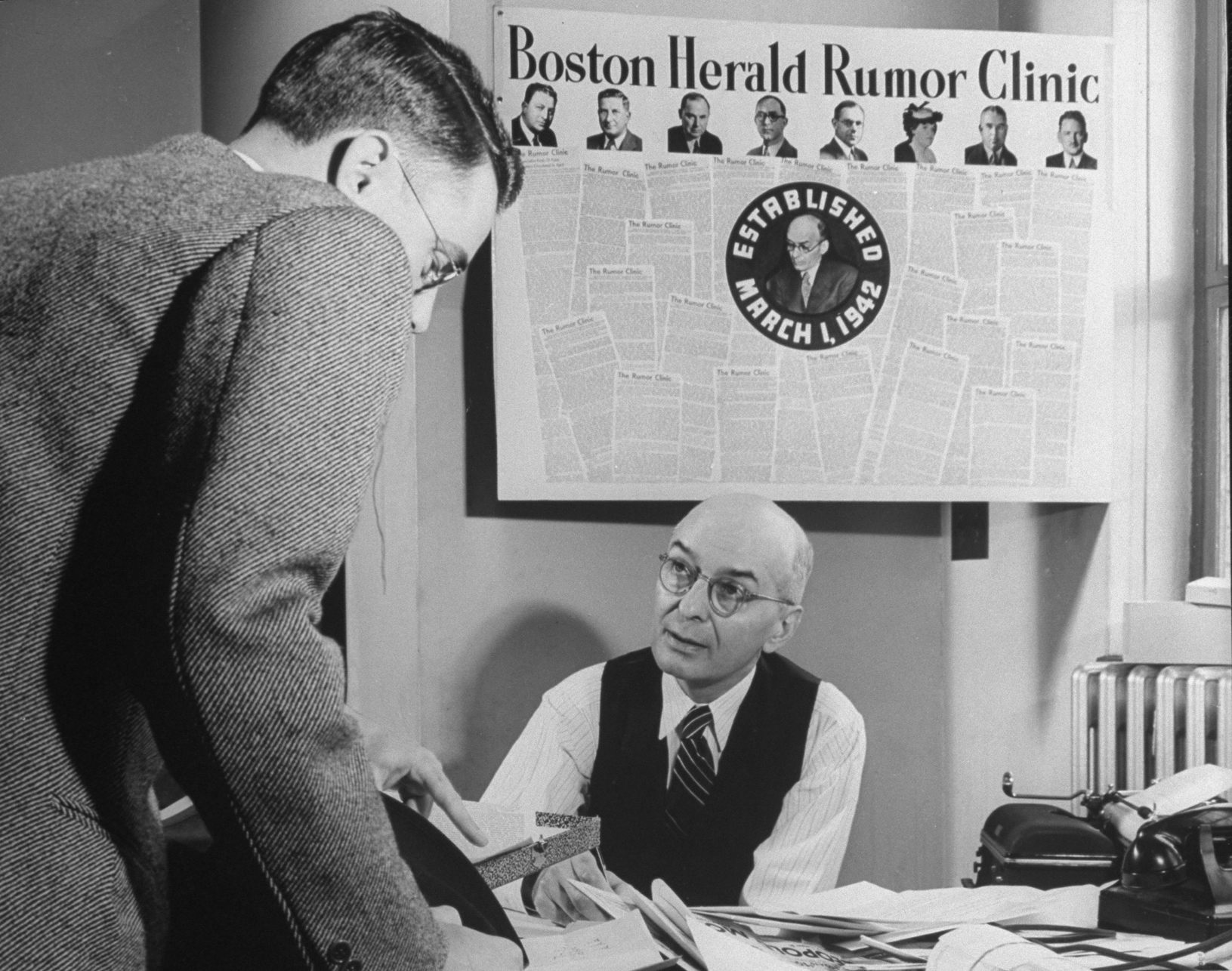

Knapp’s clinic was already up and running, despite the government considering scrapping the Rumor Project altogether. He formed a collaboration with the Boston Herald, and on March 1, 1942, the Boston Herald Rumor Clinic was established. Using a listening network of “morale wardens,” each Sunday, in a column also called Rumor Clinic, the newspaper refuted a common rumor. The rumor was placed in italics, followed by the word FACT.

Rumor: “Soldiers are being charged exorbitant prices in Army canteens for cigarettes and beer, etc.

FACT: Army Public Relations says, “False! Post exchanges are operated to the benefit of the soldiers. Soldiers are able to purchase commodities at the exchanges at GREATLY REDUCED RATES!”

The weekly refutation of a rumor that had been sent in by a reader often included how the rumor could have spread and where it likely originated. The text of the columns was attached to paystubs, posted on bulletin boards at factories, and dispersed in other ways for widespread circulation. According to The Jewish Veteran, Volumes 10-12, experts at the Boston clinic agreed that it was better to “drag a false rumor into the open, reply to it, disinfect it, than allow it to fester and spread like a poison.”

In addition to the newspaper and its listening network of 300 morale wardens (bartenders, factory workers, waitresses, and countless other civilians who reported and tracked down rumors), the Boston Herald Rumor Clinic included the Division of Propaganda Research, set up within the Massachusetts Committee on Public Safety. Knapp ran the division, along with Harvard psychology professor Gordon Allport.

Reader’s Digest and American Mercury ran feature stories about the Boston Herald’s pioneering efforts. The articles encouraged readers:

Send in your rumors! What wild, damaging, morale-eroding stories similar to those described in this article are current in your community? Readers who wish to help the Boston Rumor Clinic, and further the organization of similar clinics throughout the country, are urged to put such stories in writing and send them to Robert H. Knapp.

Soon after the articles ran, other clinics began cropping up across the United States. At one time, there were at least a dozen clinics in operation, in cities such as San Francisco, Philadelphia, and Syracuse. Some clinics were set up by social scientists. Others were operated by women’s groups, students, and university clubs. Rumor clinics became a new way for civilians to get involved in the war effort.

The Roosevelt administration frowned upon these independent initiatives. It had established OWI to control the flow of information. For a brief time, OWI coordinated with Knapp and Allport at the Boston clinic, as well as various other clinics in the U.S. The Boston relationship deteriorated after Allport criticized a report released by OWI, which attacked local clinics and their methods for researching rumors.

Eventually, the government went on the warpath, launching a campaign against the local clinics. A set of guidelines was issued in October of 1942, outlining how the clinics should run. Groups that wanted to set up new rumor clinics were sent an extensive questionnaire. For those who managed to get through the labor-intensive process, they were then sent a “rumor bible.” The bible outlined an organizational structure, requiring each clinic to have a project director, research director, an educational director, analytical assistants, field reporters, and a general advisory council. Most groups lacked the time and resources to meet OWI’s extravagant requirements, and the concept became entangled in a web of bureaucracy and red tape.

Aside from detailing the processes, the “bible” also criticized how the Boston clinic researched rumors and used examples from the Boston Herald column to demonstrate the various “mistakes” that were being made by Knapp and his team. But OWI didn’t stop there. They went on to condemn the clinics in a 1943 New York Times feature story, stating that the attempts to thwart rumors actually helped spread them. By the time World War II ended, the nation’s Rumor Clinics had vanished.

What might be thought of as an extreme use of resources today was viewed as a necessary public intervention back then. Knapp likened a rumor to a torpedo. “Once launched,” he wrote, “it travels of its own power.”

LIFE magazine even tested the theory in 1942, when the clinics were still in operation. They had a man tell a random stranger on the street that the chimneys in Boston could hide anti-aircraft. Not long after, rumor spread that Boston’s rooftops were bristled with guns.

Knapp wrote in his 1944 thesis that rumors “express and gratify the emotional needs” of communities during periods of social duress. They arise, in his opinion, to “express in simple and rationalized terms the uncertainties and hostilities which so many feel.” In other words, one man’s rumor is another man’s reality—until refuted and replaced with FACT.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook