Against the Odds, A 40-Year Old West African Village in South Carolina Has Thrived

“This is very much an American story.”

Oyotunji’s front gate, which is decorative rather than practical. No walls surround the 25-acre village. (Photo: Molly McArdle)

The road to Oyotunji turns off State Highway 17, less than 10 minutes away from Interstate 95 and under an hour from Charleston and Hilton Head. Highway 17 unspools along the coastline from Savannah to Myrtle Beach and further up into North Carolina, but this stretch—a tall corridor of green even in winter—is unhurried. There is a convenience store with no ATM and, a bit down the road, a gas station with a broken one. (The next closest option is in Yemassee, a half hour drive away.) The drive through the woods is a short one, but it’s enough to feel transformative. The signage helps too, one side in Yoruba and the other in English:

NOTICE

You are leaving the U.S.

You are entering the Yoruba Kingdom.

“Kabo sile wa,” the sign says, decorated in flags and a crown. “Welcome to our land.”

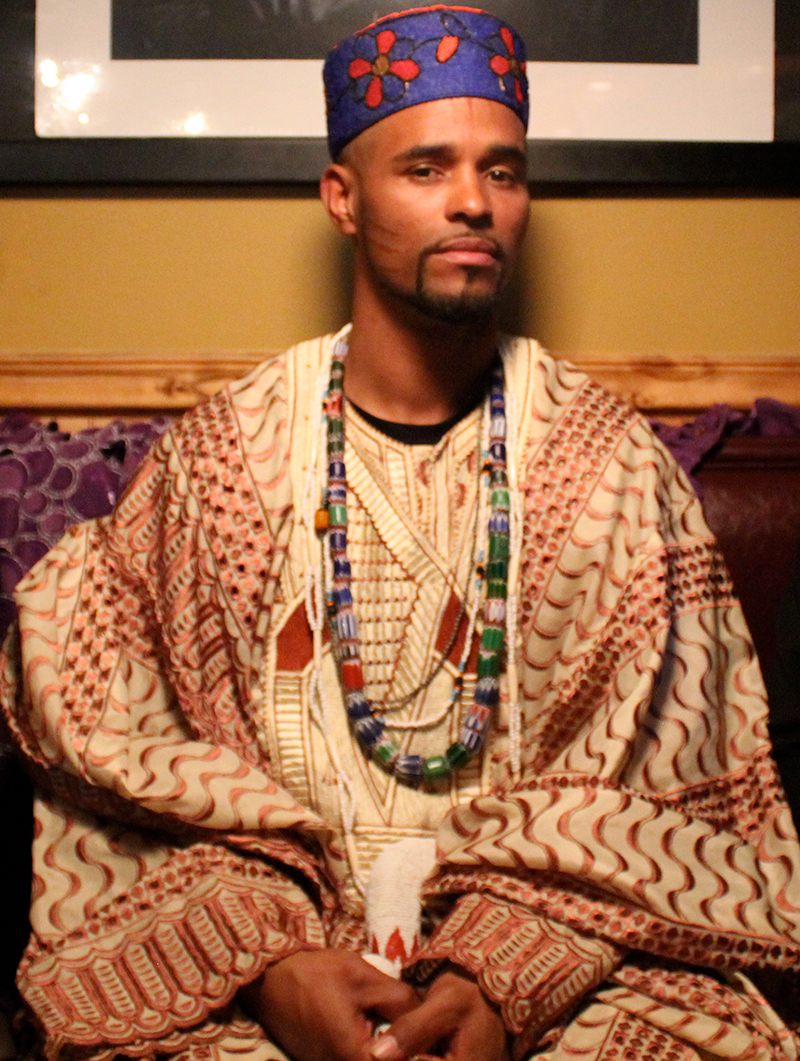

Oba Adejuyigbe Adefunmi II wearing a traditional crown. (Photo: Courtesy Oyotunji)

At its founding in 1970, Oyotunji African Village never promised its residents a perfect way of life. But it did offer them an idea equally radical: a world without Europe, a space outside white supremacy. A tiny village in South Carolina whose population has waxed and waned from as many as 200 to as few as 25 residents, it has since transformed from a bustling separatist community to a smaller and more-focused religious one.

Oba Adejuyigbe Adefunmi II was born in Oyotunji. At 39, he’s been the leader of this small community for over 10 years. He is a handsome, charismatic man. Ritual marks, three lines, run parallel across each cheekbone and perpendicular down his forehead. The garment he wears, white and embroidered, is beautiful and billowing. One woman, Oyotunji resident Ofun Laiye Adesoji, brings him a glass of water covered by a napkin. Another woman, visitor Ase Jones, moves in and out of the courtyard where he sits, periodically stopping to listen to the Oba, or leader.

The entrance to Oyotunji African Village from South Carolina’ State Highway 17. (Photo: Molly McArdle)

“Oyotunji, this was built on old planation land,” he says. “The Tomotley plantation is right through the woods over there. You can go straight through the woods, less than 200, 300 feet away,” he says. “Africans worked all of this.”

Visitors enter Oyotunji through an imposing gate, painted red and khaki, with a crenelated top. It’s decorative rather than practical; no walls surround the 25-acre village. A child’s bike leans against a low-slung building, and behind that rise pines and oaks, strung with moss. The village is residential compounds, a café and marketplace, public spaces, and religious ones. There are small garden plots, ancestral altars, above-ground tombs, and at least eight temples dedicated to separate orishas—deities in the Yoruba pantheon that can be described as aspects of a single god, a conceptual framework not unfamiliar to Hinduism or Catholicism. The physical reality of this place is explicitly African. Its commanding entryway looks Hausa. Its flag takes its design partly from Ethiopia (the colors red, gold, green) and partly from Egypt (the ankh). Its afin, or palace, is modeled after Ile Ife’s, in Nigeria. The village’s name, referencing the Yoruba empire that dominated southwestern Nigeria between the 15th and the 19th centuries, means “Oyo rises again.”

The foreignness of the place has made for heated local gossip. “There are many rumors about what we do here,” says Adesoji, who gives me a tour of the grounds. “We cook people. We eat dogs. If you go in, you never come out.”

Both Yoruba and English are featured on Oyotunji’s bilingual welcome sign. (Photo: Molly McArdle)

Coverage from predominantly white media outlets, too, has ranged from skeptical to lurid to mocking. In 2015, Oyotunji was included on a list called “Here Are the 13 Weirdest Places You Can Possibly Go in South Carolina.” It’s similarly been included in books, 2008’s Weird U.S. and 2007’s Weird Carolinas. In 2009, British travel presenter Alan Whicker, though he selected a visit to the village as his “ultimate travel experience” for The Guardian, describes Oyotunji as “some ridiculous Disney fantasy.” Its leader, he says, dressed in “the exotic robes of some imagined” (and so fake) “tribal deity” and has the “penetrating eyes of an ambulance-chasing lawyer.” An Orlando Sentinel article from 1987, titled “S. Carolina ‘Voudou’ Colony Unsettles Local Whites,” vividly describes the ritual slaughter of a chicken. “King or Con Man, the Controversial Ruler of Yoruba, SC, Is Really Just Walter from Detroit,” from a 1981 issue of People speaks of sacrificial altars and bathing in blood.

Even farther back, a 1971 story from Charleston’s News & Courier reports with restrained glee, just one year after Oyotunji’s founding, that “the village shows that black man [sic] can function without the man around. Life without ‘the man’ does not, however, exclude his food stamps.”

Oyotunji’s rejoinder appeared shortly thereafter as a News & Courier editorial response by its founder, titled “Pay for Slavery”:

“You could have reminded all Americans that having gotten something for nothing, it’s time to pay back,” he writes, “also that an honorable people, rather than hide behind guilty welfare programs, would be paying the blacks unconditional reparations in cash, land, technology, and material. For indeed, if true justice prevailed, some 15 million white Americans and their offspring in perpetuity should be committed to work free for blacks until the year 2221.”

Oyotunji is not a victim of bad press because it’s not a victim—the approval of white people is something Oyotunji was designed not to need. Oyotunji speaks for itself.

Ofuntola Oseijeman Adelabu Adefunmi I, the current Oba’s father, founded Oyotunji in 1970. Adefunmi I’s parents, followers of Marcus Garvey, gave him the name Walter Eugene King in Detroit in 1928. He was raised a Baptist, but from a young age he questioned why the religious figures his family worshiped did not look like them. Adesoji repeats the story during the tour. “He asked, ‘Why is it that we don’t have any African gods?’ The pastor told him that’s because we have none. That kind of infuriated him.”

The young King went on to become a commercial artist and modern dancer. As a member of Katherine Dunham’s groundbreaking modern dance troupe (one that would help launch the careers of Alvin Ailey and Eartha Kitt), he traveled all over the world. “When he got to Haiti he saw Yoruba culture in its full glory,” Adesoji says. “He ate the food, he saw the clothes, he also saw the community come together for the orisha, something he never saw people do in America.”

Oyotunji’s main thoroughfare. “When I came home, a lot of things needed to be rebuilt,” the Oba says. “We had to jack stuff up and dig stuff down, it was like a historical preservation board.” (Photo: Molly McArdle)

The experience changed him. In 1959, he went on to study Santería in Matanzas, Cuba, where he became the first American initiate to the priesthood of Obatala, the orisha responsible for creating humankind. He returned to Harlem and began organizing. He helped found first the Shango Temple and then, on his own, the Yoruba Temple. He took the name Nana Oseijeman, which later expanded to Ofuntola Oseijeman Adelabu Adefunmi. “The first Oba’s mission,” Adesoji says, was “to make sure that no one would ever have to go through what he went through as a child, trying to find where he came from.”

Adefunmi I stayed in New York through the end of the decade, continuing to expand and promote his interpretation of Yoruba culture and religion, which moved steadily away from the syncretic (a blend of religious and social cultures, including colonial) framework of Cuban Santería. “Lighter skinned priests had a higher place on the hierarchy,” says Kenja McCray, a history Ph.D. candidate at Georgia State University who wrote her master’s thesis on Oyotunji.

King Adefunmi I sitting in state during festival. (Photo: Courtesy Oyotunji)

Adefunmi I was also moving in black nationalist circles, founding a political party that encouraged the creation of an independent African state on American soil, and (as Oyotunji’s website claims) popularizing the dashiki. University of Houston sociologist Mary Curry, in her 1997 book Making the Gods in New York, charts Adefunmi I’s widening influence during this period. “A number of black Americans received their African names from Adefunmi I,” she says, “and some of these began to wear African dress whether they converted to the Yoruba religion or not.” Amiri Baraka, though not a member of the Yoruba Temple, had Adefunmi I officiate his wedding ceremony. (Later on, he would go on to criticize Oyotunji in a condescending 1978 New Republic story.)

By 1969, Adefunmi I had begun to receive death threats. Mama Keke, an Osun priestess from Barbados and one of the founding members of Adefunmi I’s Yoruba Temple, offered him some advice. “Mama Keke had to let him know if you really want to do something for Africans that are living in America, you have to establish land.” Adesoji gestures to the woods around her. “This is our way of sticking it to the man, to be able to come back to the very land where our ancestors were bought and sold.”

And so Adefunmi I went south.

“Rome wasn’t built in a day; Oyotunji wasn’t either,” Adefunmi I reflected to Davidson professor Tracey Hucks at the end of his reign. Hucks spoke with him extensively for her 2012 book, Yoruba Traditions & African American Religious Nationalism, which is as much a biography of Oyotunji as it is a social, religious, and political history. “We never intended to go back to 16th century Nigeria,” he told her. “We began this way out of necessity and to learn how to survive.”

His son, the current Oba, acts and speaks with a mixture of formality and informality, sometimes even performing two different versions of the same action. When we first meet, he says something in Yoruba—a greeting—and waves his irukere, a handle with white horse’s tail hair and a traditional symbol of royalty, over me. Then he smiles and says in English, hello, and shakes my hand. He moves between goofy jokes, anecdotes animated by dramatic voices, stories of his father that mix criticism and respect, and rhetoric about Oyotunji’s national, global, historical importance. These aren’t necessarily contradictions.

All residents of Oyotunji must start and maintain their own ancestor shrine, which includes bringing the ancestors fresh water every morning. (Photo: Molly McArdle)

He tells the story of how Oyotunji came here, to the spot we sit on. “My father purchased this land from a local, Mr. Smalls,” he says. “That family obviously got this land from the Civil War allotment, the 40 acres. The mule was made up.” (General Sherman did in fact try to resettle slaves in this area.) He smiles, and the two women watch us laugh.

People who moved to Oyotunji opted into, for as long as they decided to remain, a profoundly different life. It wasn’t simply that they lived in an all-black community. After all, those had existed in America since the invention of race (think Eatonville, Florida; Nicodemus, Kansas; the Gullah/Geechee-dominated Sea Islands in South Carolina; the antebellum south’s many maroon communities). They lived in a place stripped, as much as possible, of European cultural artifacts and traditions.

Residents taught themselves Yoruba and wore African clothes. (Exceptions were made for rain and winter wear.) They also had adjust to life within a highly hierarchical structure: a kingdom, complete with a king. Daily life had to be newly organized around orisha and ancestor worship as well as dokpwe, required communal work such as building or gardening. Years and lives were measured with a Yoruba, rather than Christian, schedule of annual festivals and rites of passage. And moving to the village up until the ‘80s also meant moving to a place without electricity or running water.

King Adefunmi I dances before the village. (Photo: Courtesy Oyotunji)

“At the time of Oyotuji’s founding, it was a segregated community, so it reflected the segregation of contemporary America,” says M. Kamari Clarke, whose 2004 book, Mapping Yoruba Networks: Power and Agency in the Making of Transnational Communities, makes a case study of Oyotunji. “It forced blacks to create a black movement, to create a black empire. It was a site for empowerment.”

So effective has Oyotunji been at this task that television shows (Roots) and movies (Glory) have tapped villagers to perform on screen as “real” Africans. The village also makes a cameo in gay poet and filmmaker Marlon Riggs’s 1995 documentary, Black Is…Black Ain’t, a masterpiece of collage and an incisive look at gender, sexuality, and blackness, made at the end of his life. (He would die of AIDS-related complications, just before the documentary’s completion, in 1994.) Halfway through the film Adefumni I appears accompanied by a wife, Iya Orite Olasowo, and a chief, unidentified in the transcript, to speak about Oyotunji.

“We realized that we could not really develop African civilization and culture to its fullest degree in an American city, so it became necessary then to leave the urban areas and found our own community,” Adefunmi says in the film.

Oyotunji’s Temple of Shango, the orisha of thunder and leadership, among other qualities. “Boy Scouts, Girl Gcouts, fraternities in colleges, Skull and Bones, masons, the president of the United States, all go through Shango rituals,” says resident Ofun Laiye Adesoji, “whether they know that that’s what they are doing or not.” (Photo: Molly McArdle)

The current Oba presents a different, more malleable message than the one presented in Riggs’s movie. “We’re more tolerant as a community,” he says. “Many years ago Oyotunji was quite the Disciplineville.”

The population has changed along with its mission. In 1973, the Atlanta Journal Constitution tallied 24 residents, in 1977 art historian Mikelle Smith Omari counted around 100, in 1989 Omari found 35. Harry Lefever, a Spelman-based sociologist, estimated Oyotunji to have 30 residents when he visited in 1995 and again in 1997. When I asked Adesoji how many people were currently living in Oyotunji, she said about 24. The only minors present are her three grandchildren.

“In the 1970s it was like the thing to do, it was like going to a rave today,” she says. Nowadays, Oyotunji more like a monastery than a commune.

“The actual village’s population is really small, but the footprint it made is much larger,” Kenja McCray says, calling Oyotunji “the Vodu Vatican.” Hucks’s book records a priestess’s own nickname: “the Yoruba University.” The village has initiated over 300 priests into orisha worship in just the past four years.

“We are very thankful that now because of what the first Oba did,” says Adesoji. Today it’s more acceptable to be a Yoruba priest. “You don’t have to worry about people calling you a devil.” She pauses, thinking. “Well, a witch doctor is okay. ‘Cause that’s kind of like, you know, what we are. If you want to call it that.”

Marriage comes up early in Adesoji’s tour. This is no accident: one of the village’s most famous traits is also its most controversial. Some of its residents practice polygamy.

The village’s founder, Adefumni I, had throughout the course of his life a total of 17 wives. He also had 28 children, of whom the current Oba was number 14. Today, Adefunmi II has three wives and five children. This, when the mainstream media does cover Oyotunji, is where the camera most often zooms in.

In 1988, Adefunmi I appeared on an episode of Oprah, where the iconic host introduced him as “king of probably the most unusual community in the United States.”

The interview was fraught, from the start, as Oprah zeroed in on the village’s sexual practices. “I find it interesting that this is going on in South Carolina of all places,” Oprah says. “I know your mamas are shocked,” she says, addressing the four women, who have not yet spoken.

“A king is expected to have in his palace all women who have no husbands, women who have been cast out, who are too unattractive to get husbands. The king is expected to marry all of those persons. He does not necessarily have nuptial relationships with them, but they are still called king’s wives,” Adefunmi I explains.

“To marry them all? Everybody else?” Oprah looks genuinely surprised. “Everybody else who’s single?”

Adefunmi I tries to makes the case that polygamy is a pragmatic, albeit different, way to organize society. “In the Yoruba culture the purpose of marriage essentially is based on economics,” he says, but it’s a tough sell. He’s in the wrong room.

Adesoji looks at the segment as a missed opportunity. “It kind of turned into some crazy thing,” Adesoji explains. She mimics the questions asked, “Well how do you take care of all the women? Do you have sex with all the women?” She is right that sex was at the heart of Oprah’s line of questioning. “That’s really not what the first Oba went on there to do. He really went there to explain that this is how the African culture sustains its nations. You don’t want to have any single women in the nation that cannot take care of themselves. The goal is for everyone to be married.”

Oyotunji’s Temple of Osun. “We like to refer to her respectfully as the Patti LaBelle of all the orisha,” explains Adesoji. (Photo: Molly McArdle)

Kenja McCray paraphrases the common arguments for polygamy, namely that cheating is so common in monogamous relationships that polygamy is the more honest option. Rather than hide an affair, additional relationships are openly acknowledged and so negotiable. But polygamy is also contested in Yoruba religious communities beyond Oyotunji. Those critiques ask if the practice is just, McCray explains, “being a player by another name.” In a polygamous relationship, “the central spouse is more privileged than the other spouses,” and it’s men who overwhelmingly have multiple wives, not the other way around. But McCray has also talked to women in polygynous relationships who defend it on feminist grounds as well. (Think of the childcare benefits to having multiple partners, for instance.)

“These relationships are really complicated, which is why I didn’t write them off. At what point do women use these relationships to leverage what they want out of life?” McCray asks, weighing the question. “I can’t tell whether some women are using it as a kind of transgressive sexuality,” McCray continues. “If you are being transgressive, why stop with heteronormativity?

Oyotunji’s cafe and marketplace. The Oba estimates at least two to three thousand tourists pass through annually. (Photo: Molly McArdle)

Gender plays an enormous role in life at Oyotunji. It determines the rites of passage you undergo, it grants you membership in a gendered group, it governs whom you marry and the nature of that relationship. Still the community’s understanding of gender (and to a certain extent sexuality) is something that has been and will continue to be negotiated. Even as Adesoji described the different tasks assigned to young men and women as they come of age, she rails against the idea that it’s fundamentally sexist. “There’s no such thing as a man’s job or a women’s job. Everyone’s out trying to make a living for the house, that’s how it’s always been,” she says.

Academics have backed up that idea. Hucks, author of Yoruba Traditions and African American Religious Nationalism, describes “a core group of capable and compelling women” she encountered when she first started her research in Oyotunji in the 1990s. “They served as chiefs, sat on governing boards, and participated in major decisions that shaped the direction of the village.”

The power they held was power they had fought for. Thanks to a concerted effort, in 1974, women got expanded rights (including the right to own property within the village) and compulsory polygyny was banned. In 1992, the village opened the Ifa priesthood to women, which gave them access to divinatory tools used in personal, communal, and transactional readings.

A look back at Oyotunji from the village vegetable gardens. “Our culture and religion is a nature religion,” the Oba says. “If you want to understand this culture, you got to understand the trees, the woods, and that right there, the dirt.” (Photo: Molly McArdle)

Adesoji shows me the temple of Olokun, the orisha of the ocean’s deepest regions. “He is a hermaphrodite,” Adesoji says. “He’s both male and female. He represents the curves in an African woman’s body or the feeling you get when you hear the beat of the drum.”

“We thank him for allowing our ancestors to go all over the world so that we would have history,” she says of this deity who lives across genders (if not quite yet beyond gendered pronouns). “He is the orisha of the African people.”

King Adefunmi II sitting in state. (Photo: Courtesy Oyotunji)

Adefunmi II got the call his father had died while driving over the Seven Mile Bridge in Key West in 2005. He was not yet 30. “When I came home, a lot of things needed to be rebuilt,” he says. “We had to jack stuff up and dig stuff down, it was like a historical preservation board.”

Now more than a decade after the death of its charismatic founder, Oyotunji has evolved but not slowed down.

The new king has reframed Oyotunji’s rural existence as an eco-friendly alternative, seeking out grants for sustainable farming and building. “This is a nature religion,” he explains. “If you want to understand this culture, you got to understand the trees, the woods, and that right there, the dirt.”

As Adesoji and I ate the village’s miracle crop of spicy kale, she reflected on her own increased independence. “Why not learn how to grow your own food?” Adesoji asks. “Growing up in Miami, if a hurricane came—good god almighty—the grocery stories are empty, there is no electricity, so what do you do what do you eat? You pretty much got to drive maybe 100 miles before you can get to a grocery store that has food.” I take another bite: it tastes something like wasabi. I save a few leaves for the drive home.

Oyotunji also continues to welcome religious devotees, or aborisha, who come to stay or study every year. There is no official tally but the king estimates that 2,000-3,000 visit annually.

Oyotunji’s Temple of Olokun, the orisha of the deepest water. “If it were not Olokun our ancestors would be at the bottom of the ocean with all those treasure ships,” explains Adesoji. “He is where all life comes from.” (Photo: Molly McArdle)

During my visit, I met one of these visitors, Ase Jones, who had been in Oyotunji for 10 days. A woman somewhere in her 20s, Jones was sweet and bashful, describing her home in Dallas and her community’s reaction to her religious beliefs in a low, quiet tone. She wasn’t sure how long she’d stay in Oyotunji. “I guess you’d call me an aborisha because I do practice the cultural traditions back at home. I wanted to embrace it. I’m supposed to be going to Nigeria in February so I wanted to come here and get a feel for it,” she says.

“While she’s here we’ll finish up the adobe house,” the Oba says, motioning to a nearby building-in-progress, part sandbag, part cement, part chicken wire, part multi-colored glass bottles. The Oba has been experimenting with superadobe construction, a durable, cheap, and easy construction method that uses sandbags as its primary material. These structure’s thick walls should, like traditional adobe buildings, regulate the interior’s temperature without need for central air.

“She’ll become one of the people who will helped to put a stone in the castle,” the Oba says of Jones. “Oyotunji was not built by one or two people. It was built by a lot of people. It’s amazing.”

People also come to the village looking for spiritual or bodily help; these clients also help sustain the village. M. Kamari Clarke recalls the large number of people she saw come to Oyotunji in the ‘90s. “That was at the height of HIV/AIDs and during the rise of the prison industrial complex,” she says, “I saw people come in and out, people would bring a daughter or son, people who needed help. They would drop them off for a day to work with a given priest.” Services, which range from $150 to $300 on Oyotunji’s website, could include a traditional naming ceremony, gendered coming of age rituals, or divinatory readings, wherein a priest communicates with a client’s ancestors seeking specific instructions on what orisha to ask a favor of or honor and in what ways.

The income earned from these services form a major part of Oyotunji’s economy. This turn outwards, motivated in part by Oyotunji’s declining residential numbers, came from the need to be self-sustaining, says Clark. As soon as the funds were needed “things opened up very quickly.” But this fundamental shift, one that began in the 1980s, has also fostered Oyotunji’s bonds with the local community as well as Yoruba religious communities nationwide.

“This is very much an American story,” says Kenja McCray. She is talking about Oyotunji but she is also talking about a friend of hers. This friend was born in Oyotunji, has tribal markings and a Yoruba name, and a birth certificate that—because Orisha-Vodu naming ceremonies take place several days after birth—just read “girl” in the place where her name would be. McCray’s friend now lived outside the village and had just started a new job. “One of the people at Human Resources, when I turned in my paperwork, decided that I couldn’t be American,” her friend told her. Instead, this HR staffer, another black woman, called immigration.

This is the crux of McCray’s argument. While Oyotunji is an important part of America’s black nationalist history, the village also tells a story about who and what is American. It is difficult, if not impossible, to pry apart the systems of power governing the United States from the idea of America. America is slavery, it is genocide, it is internment and deportation and torture. McCray’s friend was punished for not complying with American, which is to say Eurocentric, standards, while remaining prototypically American. Not only does she have the conventional rights of a natural born citizen, but she also practices a cultural tradition that has been on these shores since about 1619, far longer than many American’s European ancestors. The Yoruba religion in America is older than the nation that now governs it. It is America. At least a part of it.

This is perhaps Oyotunji’s greatest achievement, its most radical and most threatening and most vital—a vision not of an African nation free of Eurocentric America, but an African America free of Europe. It’s work that began in 1970. It’s work that continues, whether or not we see it, today.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook