Meet Ann Gregory, Who Shattered Racist and Sexist Barriers in the Golf World

An unheralded sports pioneer, she was known as “The Queen of Negro Women’s Golf.”

In 1959, on a warm August evening in Bethesda, Maryland, Ann Moore Gregory ate a hamburger and went to bed. That night, every other player in the United States Golf Association Women’s Amateur tournament, which began the next day, was eating a traditional players’ dinner at the Congressional Country Club. But Gregory, the only African-American player in the tournament, had been barred from the clubhouse. So, she said later, she ate by herself. She was “happy as a lark. I didn’t feel bad. I didn’t. I just wanted to play golf, they were letting me play golf,” she said. “So I got me a hamburger, and went to bed.”

This was just one of many racist episodes suffered by Gregory over an amateur golfing career that spanned 45 years. She was, writes Rhonda Glenn in The Illustrated History of Women’s Golf, “the first black woman to compete on the national scene and, arguably, the best,” with 300 sanctioned golf tournament wins under her belt. In 1943, when she was in her early 30s, Gregory first picked up a set of clubs. Within three years, she was good enough to win the all-black Chicago Women’s Golf Association Championship. And less than 10 years after that, in 1956, she became the first African-American player to compete on the national stage, at the U.S. Women’s Amateur Championship, in Indiana. African-American men had, by this point, been competing nationally, though infrequently, since 1896.

Gregory was born Ann Moore in Aberdeen, Mississippi, in 1912. The middle child of five, she lost her family (it’s not clear how) when she was very young, and was taken in by a local white family, the Sanders. She worked as their maid, but they did support her education through to the end of high school. When she left them, in 1930, to move to Indiana, they cried like babies, Gregory told Glenn. “They said people in the north were so cold and that I didn’t deserve being treated like that. I said, “Mrs. Sanders, you’ve prepared me very well for mistreatment.”

In Gary, Indiana, Gregory met the man who would become her husband, Leroy Percy Gregory, and through him she met the other great love of her life. “He introduced me to golf before he went into the [navy],” she told the Chicago Defender, a weekly African-American paper, in 1950. “During the time he was in the [navy], I began playing more often. I entered that first tournament to prove to him that I had advanced during this absence.” Initially, golf had been a source of contention in their marriage, as it took him away from her and their only child, JoAnn. But when he went to serve in World War II, she began to gain skill and confidence on the course.

The Professional Golfers’ Association originally had no regulations relating to the race of its players. But, in 1934, it introduced a bylaw stating that it was only “for members of the Caucasian race.” Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, black male golfers attempted to challenge this ban legally. It only began to be lifted only when the PGA came under enormous public pressure, particularly after ex-champion boxer Joe Louis* drew attention to it. The “Caucasians-only” policy was maintained in general, but a few, specific black players were allowed to take part. Finally, in 1961, the ban was lifted for good.

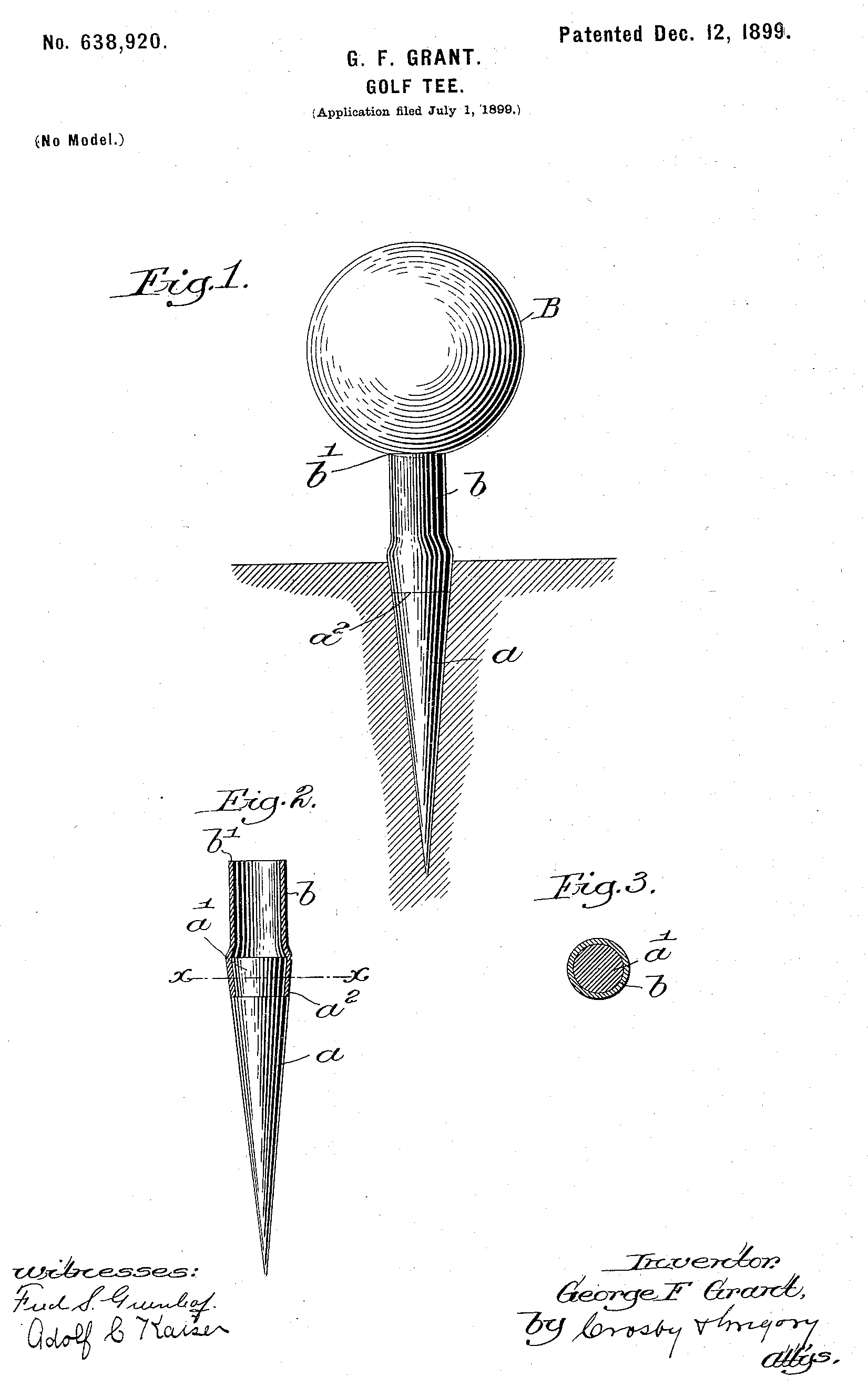

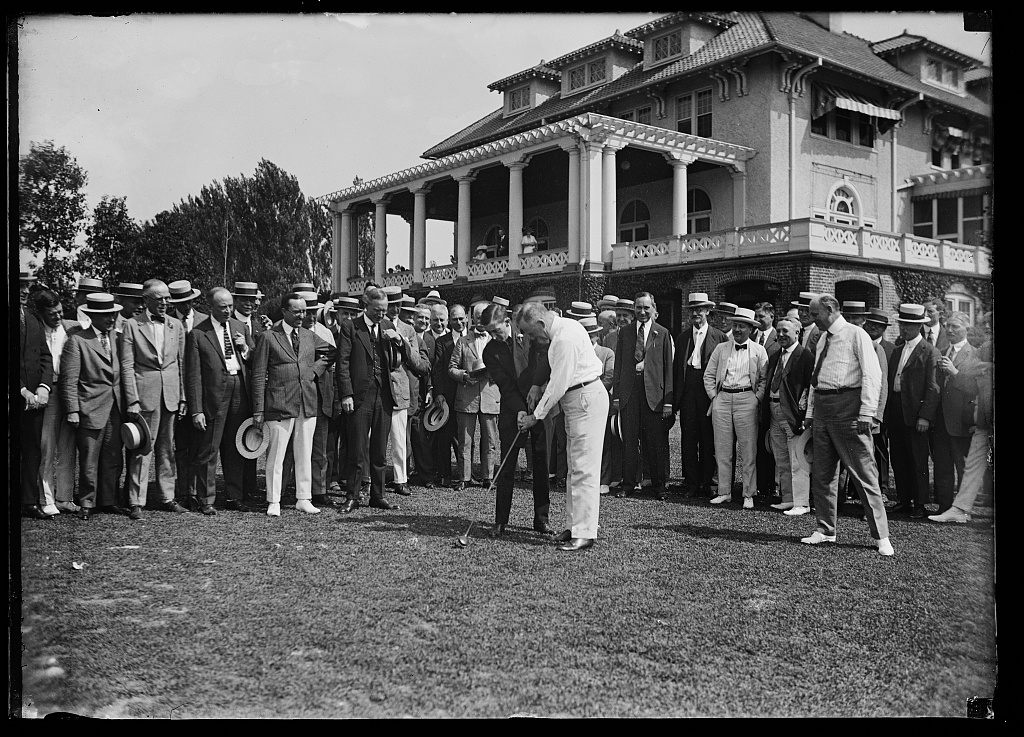

For decades before that, however, there had been no shortage of African-American golfers who found other ways to tee up outside the strictures of the PGA. From the years immediately following the Civil War, African-American men played golf with enthusiasm and, often, lots of skill. Many came to the sport as caddies—including John Shippen, who finished fifth in the 1896 U.S. Open, after discovering that he could beat every member of the club where he worked. Three years later, in 1899, an African-American doctor, George Grant, invented the wooden golf tee. But there were significant practical barriers to competitive play, including finding clubs that either accepted black golfers or catered to them. Most golfers, regardless of race, were middle class, with the disposable income necessary to maintain an interest in a time-consuming and sometimes expensive sport.

Slowly, clubs aimed at African-American golfers began to spring up in pockets around the country—Washington, D.C., Chicago, New York. From 1936, African-American women had the opportunity to play, with the launch of the Wake Robin Golf Club in D.C. Unlike many of their male peers, however, they usually came to the sport as adults, like Gregory, without the formative training of having been a caddie first. The United Golf Association (UGA) was launched in 1925, and brought many of these African-American golf collectives together. It hosted multiple amateur golf tournaments every year, across the country, and it was in these that Gregory got her start. She later began to play in tournaments for “whites” in 1947, with the famous Tam O’Shanter tournament in Chicago. (Its organizer, George S. May, had seen her practicing and issued an invitation.)

Throughout this time, Gregory had a full raft of responsibilities. Beyond her family responsibilities, she was the only, and first, African-American on the board of the local library, worked as a caterer, did volunteer work, and made regular hour-long commutes to Chicago to play with the African-American Chicago Women’s Golf Club, which had scouted her after seeing her play.

Being the only African-American person in these tournaments was sometimes troubling, she said later. “The galleries were just beautiful to me, but I was lonely. For a whole week I didn’t see any black people,” said Gregory. “My neighbors drove up from Gary to see me play the final round and, when I saw them, that’s the only time I felt funny. It just did something to me to see my black friends among all those white people, and I cried.” Being the only black player in these white tournaments ruffled feathers in the black golfing community, too. When she played in the U.S. Women’s Amateur Competition in 1956, eschewing a UGA competition on the same weekend, many were disappointed or hurt.

Playing in many of these tournaments required either direct confrontation with racism, or ignoring it. In one competition, a fellow player, Polly Riley, famously mistook her for a maid, and asked her to fetch a hanger. This Gregory did with grace and Riley, realizing her error, was deeply ashamed. Gregory policy, in these instances, was not to let racism “affect [her] mind,” she said. “It was better for me to remember that the flaw was in the racist, not in myself.”

Gregory was simply a deeply likable person. Fellow players remembered not just her prowess at the game, but also her sense of humor and compassion. But beneath that friendly exterior was an iron core. After playing at the Gleason Park segregated nine-hole golf course in Gary, Indiana, for some years, one day in the early 1960s, she made up her mind to play the public—whites-only—18-hole layout. She walked in, placed her money on the table, and told them she would be playing there today. “My tax dollars are taking care of the big course,” she is said to have told them, “and there is no way you can bar me from it.” She suggested they call the police if they had a problem with her playing. Shortly afterwards, she teed off.

Gregory’s accomplishments have been largely ignored by mainstream culture and the golf world. In all its archives, the New York Times has just two references to her, neither of which mention her pioneering role in African-American women’s golf. But in African-American newspapers she was celebrated, and heralded as “The Queen of Negro Women’s Golf.” She played right up to the end of her life, at age 76. In 1989, a year before her death, she won gold at the U.S. Senior Olympics. One day, the late M. Mickell Johnson wrote, “the world will acknowledge Mrs. Gregory as the first-class amateur who took her game to the highest level in golf”—irrespective of her race.

*Correction: This article originally misspelled the name of the boxing champ who pressured the PGA to desegregate. It was Joe Louis, not Joe Lewis.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook