Stare Into the Belly of the Earth With 17th-Century Polymath Athanasius Kircher

How a visit to Vesuvius shaped his prescient vision of a hot core.

The pair set out after midnight, clambering up steep, rugged Mount Vesuvius in the dark. The path toward the 4,200-foot summit was rough, but Athanasius Kircher and his unnamed Italian guide kept at it. They climbed and climbed until they reached a crater.

There, they were transfixed. It was awesome in every sense of the word—tremendous, terrible, fearsome.

“I saw it all lit up by fire,” Kircher later wrote, “with an intolerable exhalation of sulfur and burning bitumen.” The smell was so unbearable that Kircher kept heaving up the contents of his stomach. And he was scared, too. With the “groaning and shaking of the dreadful mountain,” he went on, “I believed I was peering into the realm of the dead, and seeing the horrid phantasms of demons.”

It was the 1630s, and the passionate Jesuit scholar, priest, and scientist—and Atlas Obscura hero—wanted a glimpse into the belly of the Earth.

Maybe things looked slightly less dyspeptic in the morning, or maybe Kircher spent the remainder of the night gathering his courage. Either way, when day broke, he climbed down into the crater. There, he saw a straight, hollow chute—“all up and down everywhere, cragged and broken,” opening into a pool “boiling with an everlasting gushing forth, and streaming of smoke and flames.” (English translations of his writings vary slightly, but they’re all powerfully sensory and overwhelming.)

Kircher went on with his life, but the scene was seared into his memory. On Vesuvius, writes Kircher biographer John Glassie, he had begun “to envision what it might be like even deeper within the earth, and how the mountains and fires and rivers and oceans might somehow all be connected.” Kircher couldn’t stop thinking about it, and he eventually put his vision into a fascinating, prescient, detailed map of the inner-workings of the planet.

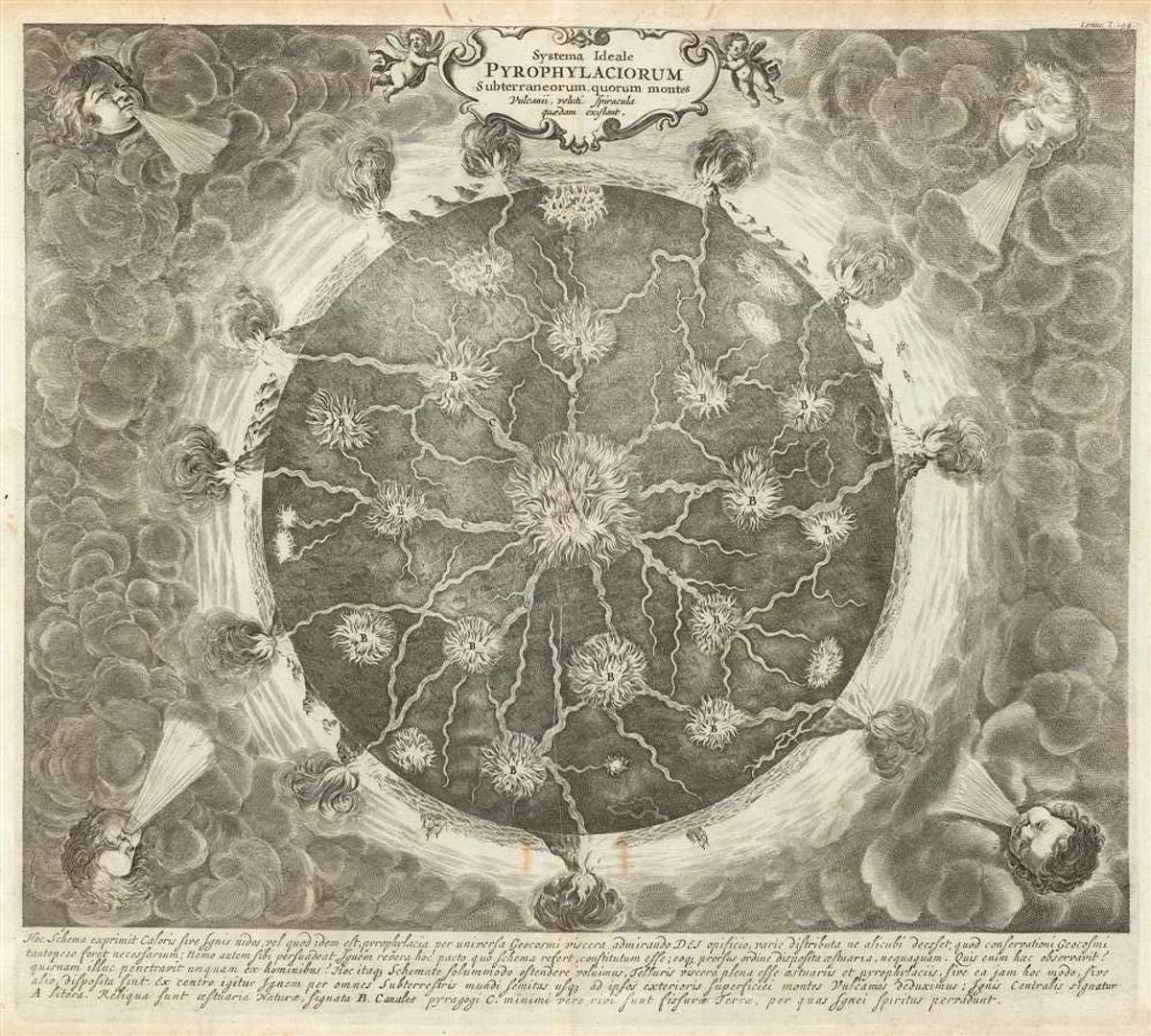

For as long as people have walked the Earth, they’ve looked up in wonder. Like many natural philosophers before him, Kircher studied the Moon, and mapped its mottled face. But Kircher also looked down, and devoted much of a hefty tome, Mundus Subterraneus, to the world beneath our feet. It was a journey, as he put it, into “the fecund womb of Nature.” Two of the prints made to accompany the 1665 edition are currently for sale through Geographicus Rare Antique Maps.

Far below us, Kircher figured, there was a series of buried lakes and rivers, which he imagined winding toward the planet’s core like blood vessels. And fire—so much fire. Nearly three decades after his trek into Vesuvius, Kircher was still trying to understand what these molten rivers might have to do with earthquakes and other natural phenomena.

At the time, a prevailing idea posited center of the Earth as a fiery warren. In the 17th century, writes archivist Frances Willmoth in the science history journal Endeavor, many natural philosophers were convinced that the Earth was “riddled with passages, large caverns, smaller channels and cavities, all capable of transmitting air, water and other substances.” Like Seneca, Aristotle, and others, Willmoth writes, some of these scientists theorized that earthquakes were the product of air and water rushing through those channels; many speculated that thunder or lightning played a role, too.

In Mundus Subterraneus, Kircher depicts the very center of the Earth as a fireball. In his print, it looks like a central lake of flame with jagged rivers stretching out to feed roughly a dozen volcanoes depicted on the surface, like vents. Elsewhere in the book, Kircher also imagined a system of underground seas and rivers, and the interplay between the water and fire. In Kircher’s view, writes Kevin Brown of Geographicus, “the volcanic system interacted with the hydrosystem by superheating parts of it, causing the movement of water to and from the surface—hence ocean currents, earthquakes, tides, and more.”

Kircher’s map looks fantastical, as does the totality of his theories, but centuries of science have borne out some of his ideas. “His hypothesis of a central source of heat inside the planet, and his realization that volcanoes and earthquakes are a global phenomenon, are now widely accepted,” NASA’s Earth Observatory notes. We know that volcanoes do tend to cluster, and that their eruptions coincide with molten movement deep within the Earth, even if they don’t quite look like Kircher thought they would.

There are many more volcanoes than Kircher’s map suggests—as many as 1,500 potentially active ones, discounting the “continuous belt” of underwater ones along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, according to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). By the agency’s count, about a third of these have erupted in recorded history. Many of the feistiest occupy what is known as the Ring of Fire, where tectonic plates collide. We also know, of course, that the core is definitely hot—up to 10,800 degrees Fahrenheit—though made mostly of iron and nickel, not an open, flickering flame.

Even as we peer ever-deeper into space, the world below our feet is largely a mystery to those of us who aren’t geologists, planetary scientists, or cavers. Nature writer Robert Macfarlane observes as much in his new book, Underland, which takes readers into crevasses, caves, and other claustrophobic corners of the world. “We can look up and see the Moon,” he said at a recent talk in New York, “but we look down and only see our feet.” Hundreds of years after Kircher climbed down into Vesuvius, there’s still much to learn about what’s down there, and you don’t need to stumble into volcano to be awestruck.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook