How a ‘Puffling Patrol’ Protects Iceland’s Puffin Babies

On the small island of Heimaey, young volunteers help out disoriented baby birds.

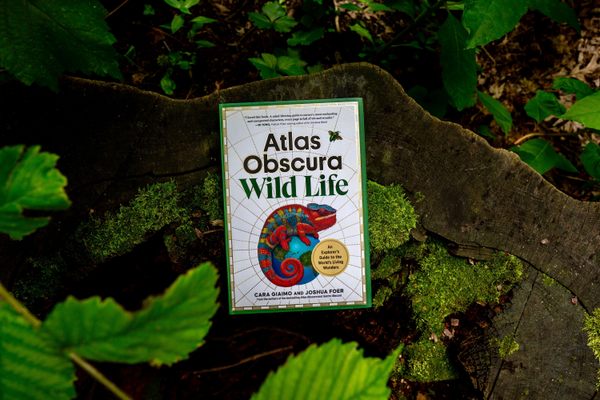

Each week, Atlas Obscura is providing a new short excerpt from our upcoming book, Wild Life: An Explorer’s Guide to the World’s Living Wonders (September 17, 2024).

Imagine an Easter egg hunt in the dark—except the eggs can run away from you.

That’s what the puffling season is like on Heimaey, a volcanic island in the Vestmannaeyjar archipelago along the southern coast of Iceland. Every year in mid-September, lost and confused baby puffins wander the streets at night. “They’re everywhere,” says Audrey Padgett, manager of the Sea Life Trust Beluga Whale Sanctuary in Heimaey. “It feels like puffins are raining from the sky.”

Heimaey is home to the world’s largest puffin colony. The neon-billed birds have dug more than a million burrows along the island’s steep, grassy cliffs, which rise above the town of 4,500 people. Once a source of food for islanders, they have more recently become some of Iceland’s most famous residents, attracting tourists and serving as unofficial mascots for the whole country. (Stuffed toy versions of the birds have become so ubiquitous as souvenirs that stores geared toward tourists are colloquially known as “puffin shops.”)

While puffins spend most of the year at sea, bobbing on the water and diving for fish, they return to the same burrow every summer to breed. From mid-April to early May, puffin pairs—who mate for life—can be spotted coming ashore to get comfy, lay eggs, and raise their chicks, who are known as pufflings.

The chicks hatch around July and are cared for by their parents for roughly 45 days. Just as the midnight sun ebbs and Iceland’s nights grow dark again, the young birds are ready to leave the colony. They’re supposed to aim for the open sea, using moonlight as their guide. However, they often become confused by the artificial lights across the harbor and end up stranded in town instead.

It’s a dangerous situation for the pufflings, who are usually too disoriented to correct their course. Instead, they wander around, swarming streetlights and making themselves vulnerable to hazards such as cars, cats, and walls.

That’s where the grassroots Puffling Patrol comes in. The human residents of Heimaey scour the streets at night, chasing down the chicks and placing them gently into cardboard boxes. They then take them to the Sea Life Trust, where the young birds are weighed, measured, and tagged. “Everyone gets into the weird habit of carrying around a puffling box,” says Ewa Malinowska, who runs the puffin hospital there.

Once they receive clean bills of health, the pufflings are taken to the cliffs and lobbed into the sea below, just like fluffy baseballs. They’ll remain at sea for two to three years before returning to the island and making a home in a burrow of their own.

Range: Puffins traverse the North Atlantic from Canada to Norway and as far south as Spain. Puffling rescue occurs on Heimaey, in Iceland.

Species: Atlantic puffin (Fratercula arctica)

How to see them: Look for clifftop colonies in coastal areas during the breeding season (late spring to late August or early September). Tourists who’d like to join the Puffling Patrol should check in at the Sea Life Trust first for guidance.

THE WILD LIFE OF: A Puffling Patrol Family

Sandra Sigvardsdóttir and her children, Íris Dröfn Gudmundsdóttir (age 8), Eva Berglind Gudmundsdóttir (age 6), and Sara Björk Gudmundsdóttir (age 15 months), live on the island of Heimaey and are famously prolific members of the Puffling Patrol. Every year, they rescue between 200 and 300 chicks during the four-week-long puffling season.

How did your family start looking for pufflings?

SANDRA: My first puffling ride was when I was three months old, and every year after that, so I don’t remember my first years as a puffling rescuer. But when I think back to being a kid, the most memorable thing is the excitement—Are we going to find some?—and the rush—Are we going to catch it? Now I try to do the same with my kids. We are like the crazy puffin family on the island—that’s how people think of us.

ÍRIS DRÖFN: I was born and raised into this. Every year, it’s what we live for.

What’s the puffling season like?

SANDRA: We go out every night, [starting] when we hear about the first puffling until we hear about the last one. So we really participate in the rescuing. It can get kind of crazy when the first puffling arrives, because everyone goes out, and you can see cars and flashlights on almost every street. There are crowds. It’s like Black Friday. And when the season ends, we start counting down to the next one.

What does a night of puffling rescuing typically entail?

SANDRA: We start looking around midnight, which is long past bedtime, so on the nights we plan to go out, the children go to bed very early. Then I wake them up when it’s time to start looking for pufflings. I do feel very lucky my children aren’t afraid of running around in the dark. On a good night, we bring home about 15 to 20 pufflings.

What kind of equipment do you need?

SANDRA: During the season, we keep boxes in our car. We put grass in the bottom of the boxes, so we can use them longer. When I was a kid, we used a box for two or three nights—then [the pufflings would] poop all over, and you cannot use the box anymore. But you don’t need much to get started. Since they arrive at night, you only need some reflective gear, flashlights, and patience.

ÍRIS DRÖFN: And pufflings.

What does a puffling feel like?

SANDRA: They’re soft and really small. You can hold them in one hand. They have a lot of down, and it’s just like the softest cotton you’ve ever touched. Sometimes if they are really small and they have too much down on their bottom and the wings, then we have to keep them at home for a few days before they can be released.

ÍRIS DRÖFN: They’re so soft, it’s like floating in the air.

Why do you enjoy helping pufflings?

ÍRIS DRÖFN: It’s fun when I go to school the day after, and I can talk to my friends about how many pufflings we found. There aren’t many parents who are as crazy as mine, so my friends don’t always get to go out every night. So we get the high score and can brag a little bit.

SANDRA: For us, the grown-ups, the joy is the happiness in the kids’ faces. There’s also the rush of trying to catch the pufflings before anything happens to them. Then when we catch one, it’s wonderful. And there’s the happy feeling of releasing them, knowing you’ve done something good.

Wild Life: An Explorer’s Guide to the World’s Living Wonders celebrates hundreds of surprising animals, plants, fungi, microbes, and more, as well as the people around the world who have dedicated their lives to understanding them. Pre-order your copy today!

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook