The Curse of the Bambino’s Statue

Illustration by Matt Lubchansky.

In the summer of 1935, visitors to the Baltimore Museum of Art were privy to a real treat. The curatorial staff had just been loaned an impressive, eight-foot-tall statue of New York Yankees star (and Baltimore native) Babe Ruth. A towering golem meticulously crafted from a ton of clay by the noted American sculptor Reuben Nakian, the statue was a tribute to the Babe’s prodigious power, showing the slugger at the tail end of the home run swing that had made him an international icon. Now, at the height of the Babe’s fame, the museum had a jewel of a piece that would surely attract patrons from all over.

It was, as New York Sun noted at its initial unveiling in Manhattan a year earlier, sure to “survive down the shadowy arches of time.”

But after 1935 all information about the statue’s whereabouts is gone. The disappearance was never solved, and few clues remain about who might have been responsible. To many historians, even hardcore sports fanatics, it’s like it never even existed.

“I’d never heard of it,” says Shawn Herne, director of development and chief curator of the Babe Ruth Birthplace Foundation in Baltimore. “My executive director, who’s been here since the early 1980s and is one of the foremost Babe Ruth experts — MLB consults with him on stuff — he had never heard of it. After so many years, you think you’ve heard all the Babe Ruth stories and come across all the Babe Ruth stuff, but this was a new one.”

The Baltimore Museum of Art has no idea what happened to the statue. “We have no records of where it went after it was here because it wasn’t ours to loan,” says Anne Mannix-Brown, a spokesperson for the BMA. “That would have been coordinated by the owner — probably the artist, in this case.”

Nakian died in 1986 — his New York Times obit, in citing his portraiture, called the Ruth statue “his most famous work in this mode” — but his son, Paul, has been actively investigating the statue’s fate for nearly 20 years. Now 78, Paul still lives in Stamford, Connecticut, where the Nakians settled in 1945. He’s realistic about the statue’s probable fate — the odds of an eight-foot-tall plaster statue surviving 80 years without expert preservation are slim — but he holds out hope it may yet turn up.

“My father went on to do things that are more exotic, but as a representational piece, the Ruth statue is a great work,” Paul Nakian says. “But could it really remain undiscovered after all these years? It’s hard to believe that.”

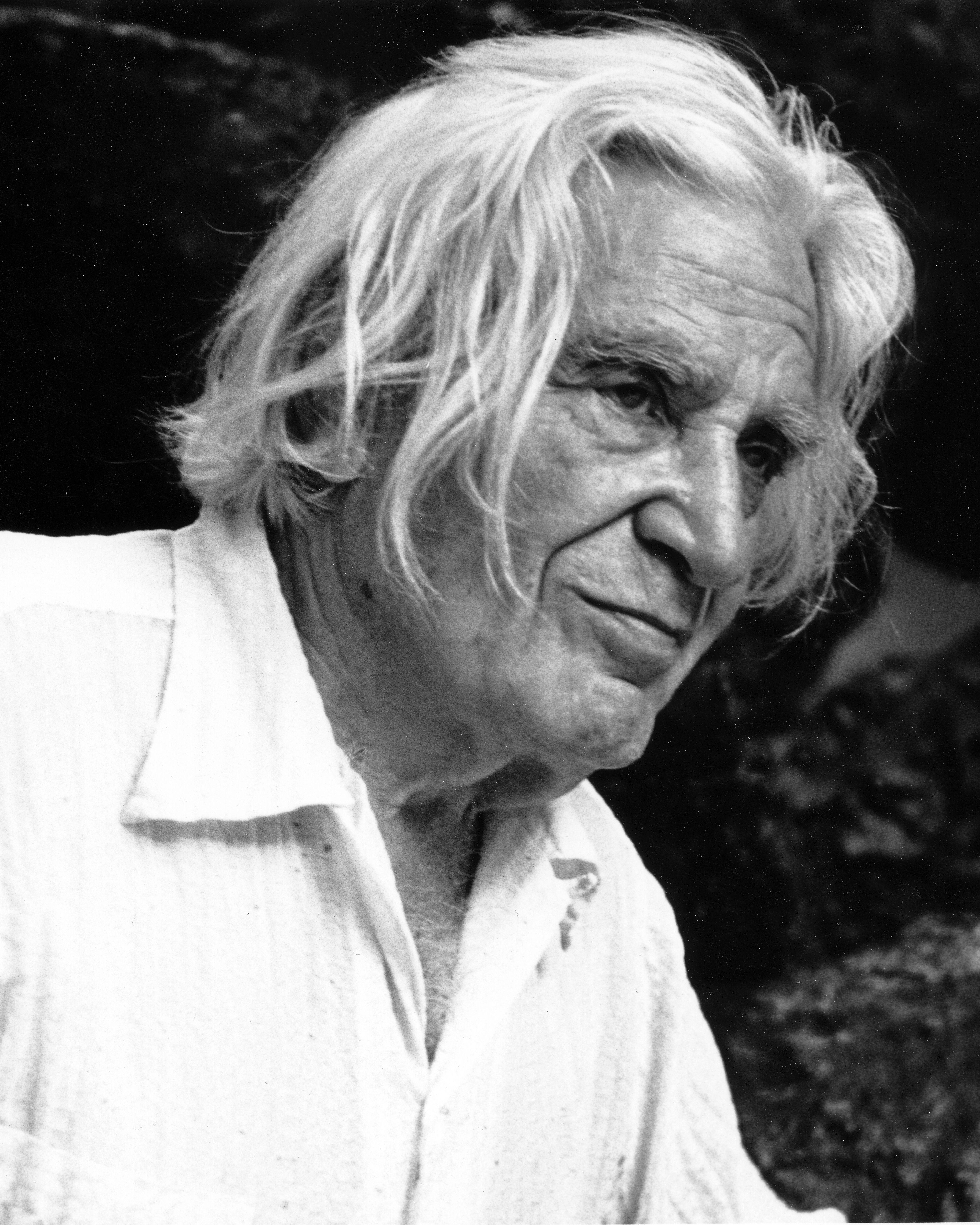

Sculptor Reuben Nakian. (Photo: © Lois Dreyer)

For Reuben Nakian, the inspiration to sculpt a likeness of Ruth came on September 30, 1927, as he sat in the stands at old Yankee Stadium and watched the Bambino smash his record 60th home run of the season. It would be six more years before he started work on the piece but, as Nakian’s official site contends, “the excitement of this day remained imprinted on his mind.”

Nakian began the project in 1933 and completed it in early 1934. At eight feet tall, the clay statue, cast in plaster, was literally larger than life and accentuated and amplified every one of Ruth’s features: his biceps, his legs, even his face. With the Babe shown in full contortion and balanced on his pivoting feet as he watches a home run sail away, the sculpture is captivating but in a mythological, comic book-type sense. He is almost impossibly muscular, but the author James Mote, who has written extensively on baseball artifacts, has called it “possibly the finest example of heroic sculpture ever created of a baseball subject.”

Promotional fliers invited the public to come down to the famed Downtown Gallery at 113 West 13th Street from February 13th to March 3rd. After that, “Babe Ruth” was put on display inside the still relatively new Rockefeller Center, where tens of thousands of people walked by its installation.

As foreboding as that prediction would become, it seems that New Yorkers grew tired of the sculpture rather quickly. Just five days after its opening, one wire story touted a growing controversy over Ruth’s appearance. “The Bambino’s legs are causing much head-shaking,” the article said. “The consensus is that they are too big.”

Even with his limited knowledge of the statue, Herne isn’t surprised to hear that was the opinion of the day. “There’s never been a good piece on Babe Ruth ever done,” he says. “Every painting, every sculpture, every drawing I’ve ever seen of him, very few have ever come close to the likeness that is Babe Ruth. He had a large torso and very scrawny legs.” Even Paul Nakian will admit the statue has “sort of an ugly mug.”

So the Downtown Gallery eventually worked out a loan agreement to ship the statue to Baltimore, the Babe’s birthplace and a city that was known at the time for being home to some of the best sculptures and statues in the country. By the summer of 1935, the statue’s transfer had been completed and the local press started to take notice once Nakian’s work went on display.

“The Babe has come back to the city where he got his start, in the form of a heroic plaster cast which dominates the main foyer of the Baltimore Museum of Art,” wrote The Baltimore Sun on June 24. The article made clear that while no one knew whether Ruth had seen the work, his teammate Lou Gehrig saw it and was “enthusiastic about the piece.” A week later, another Sun writeup called the statue “a rugged and vigorous interpretation” of Ruth that would be on display throughout the summer.

The BMA says the statue was on display in its Sculpture Hall and was supposed to have been there until mid-October 1935, but whether it was is unclear, as is what happened to the statue after its public run concluded. All anyone knows for sure is that as the real-life Babe Ruth kept socking dingers in New York, Nakian’s “Babe Ruth” disappeared and was never seen again.

Nakian’s goal had always been to get Yankees management to pay to have the statue bronzed and put on permanent display outside Yankee Stadium, but they never took him up on that offer. His best guesses as to the statue’s fate were either that it was still in the BMA’s archives or that it had been given to St. Mary’s Industrial School, where Ruth spent much of his years as a child. Alas, there has never been evidence to suggest St. Mary’s ever had possession of the statue.

Some 35 years later, Nakian was approached by some ex-BMA curators who assumed he had the statue in storage somewhere. Nakian was stunned, but also somewhat relieved it was gone. Nakian’s son confirms that his father always regarded the Ruth statue as a “corny piece of art.” As Nakian himself said in a 1981 interview, “I couldn’t afford to pay storage on it. … If it came back to me, the first thing I’d have done was smash it up.”

Ultimately, Herne isn’t shocked the statue was eventually misplaced, even though its subject was so iconic at the time. “Shows, museums, galleries in those days were really not professional organizations,” he says. “We don’t know if someone just mishandled it. Maybe an employee knocked it over, broke it into pieces, and threw it in a dumpster before somebody noticed? You just don’t know. Or someone may have said, ‘I want that piece in my home,’ cash was exchanged, and there was no record, so it gets lost to history.”

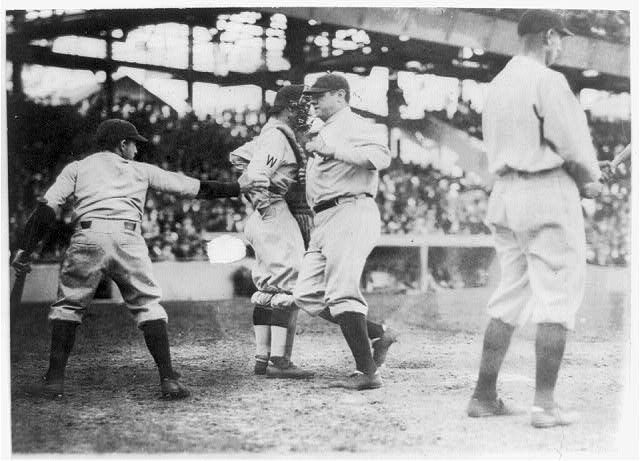

Babe Ruth. crossing the plate after making his first home run of the season, 1924. (Photo: Library of Congress)

As the chief curator at the Babe Ruth Birthplace Foundation in Baltimore, Herne oversees a collection of artifacts numbering around 10,000, split mainly between the historical site marking Ruth’s childhood home (which encompasses four Baltimore row houses) and the Sports Legend Museum near Oriole Park at Camden Yards, the home of the Baltimore Orioles. Between the two locations, there is but a single statue — of Hall of Fame Baltimore Colts quarterback Johnny Unitas.

And the large statue isn’t the only bit of Ruthian history lost to time. Herne says there are two main Ruth artifacts for which every collector or historian holds out hope. One is the home run ball from his “called shot” at the 1932 World Series in Chicago. “In my first few years here at the museum,” he says, “I must’ve been offered that ball at least six or seven times a year. People are absolutely adamant they know they have that ball. Unfortunately, there’s no way of proving.” The other is the piano Ruth supposedly dropped into Willis Pond in Sudbury, Massachusetts, in 1918 after a particularly wild party.

Herne says Nakian’s work doesn’t rise to the level of either of those objects and any perceived value on this statue, at this point, would have less to do with the subject and more to do with its creator’s reputation. “Unless it is an artist who went on to become one of the world’s renowned sculptors,” he says, “it probably wouldn’t have a tremendous amount of historical value.”

Nakian might just be such a person. His reputation as one of the more accomplished modern American sculptors has steadily grown over the decades — his “New Deal” busts of Franklin D. Roosevelt and other administration officials were also done around the time of the Ruth statue and are widely acclaimed today — and his works are still on display, including in the art-mad world of Manhattan. Some of Nakian’s work was recently selected for the debut collection of the new 66th Street gallery Rosenberg & Co. The gallery is run by Marianne Rosenberg, whose family represented some of the greatest artists of the 20th century, including Pablo Picasso.

Paul Nakian believes that such exposure from this and future New York-area exhibits, which he is negotiating, may help either stir enough interest in his father that the statue is rediscovered (if it even exists) or perhaps reproduced from the two dozen-ish photographs that have survived. “I must admit in the back of my mind,” Paul says, “if we could get someone to sponsor it, it would be an interesting thing to recreate this piece.”

The original Yankee Stadium, which Ruth opened in April 1923 with a three-run homer in its first game, hosted its final one in 2008. New Yankee Stadium, just six years old, stands in its stead. Paul Nakian’s continuing hope is that if his father’s statue were to be somehow found, Yankees management would (finally) agree to have it cast in bronze and placed outside this new structure. Otherwise, a cursed statue like this probably belongs in another city. Maybe Boston.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook