Inside the Abandoned Babylon That Saddam Hussein Built

“If I could, I would go without shoes here, because it’s a holy place,” says a guide to the ancient site.

Meky Mohamed Farhoud grew up in a small village called Qawarish on the edge of the Tigris River, among pomegranate, orange, and date trees. The village is just steps away from the ruins of ancient Babylon, the Mesopotamian kingdom that Hammurabi helped build into one of the world’s largest cities. As a child, Farhoud played soccer in fields studded with ceramic shards and bricks from long ago. “I had a golden childhood,” he says.

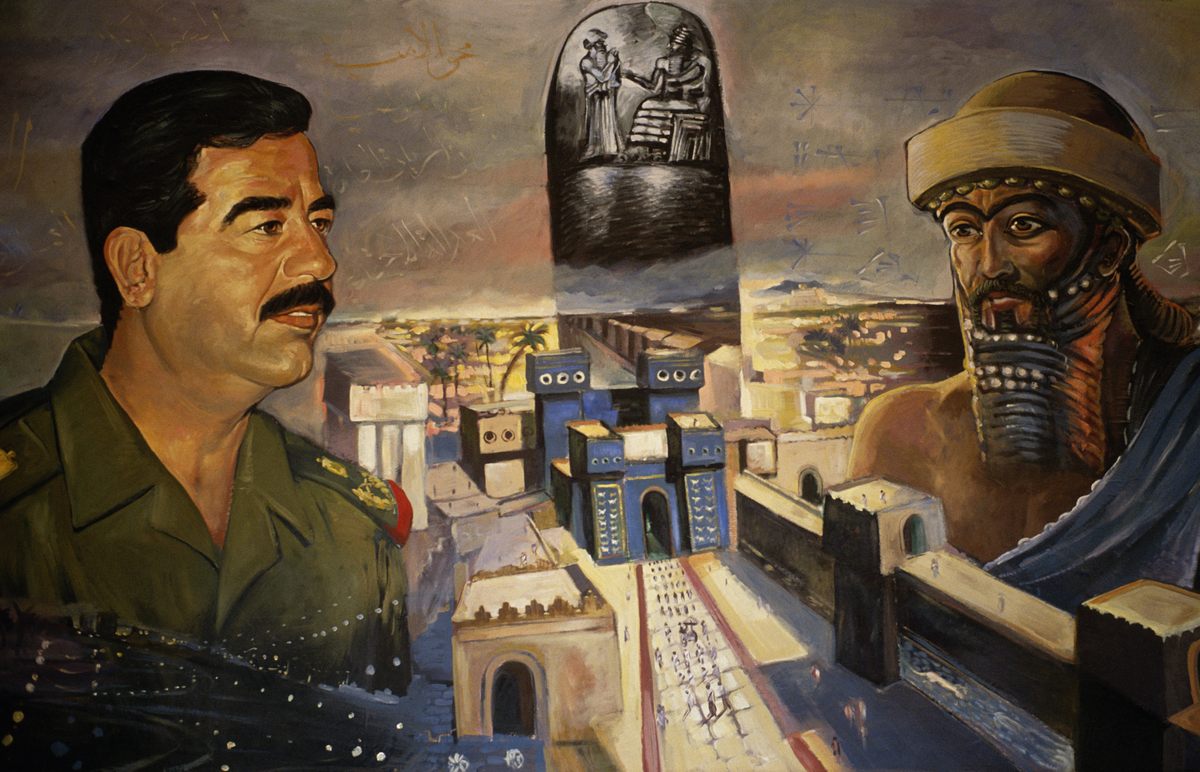

But Qawarish’s famed location ultimately doomed it. In the 1980s, during the Iran-Iraq War, Saddam Hussein became obsessed with the Babylonian ruler Nebuchadnezzar, who is notorious for waging bloody wars to seize large swaths of current-day Iran and Israel. Saddam saw himself as a modern reincarnation of Nebuchadnezzar, and to prove it, he spent millions building a massive reconstruction of Babylon.

Saddam wanted a palace to overlook his works, and Qawarish had the unfortunate luck of standing in the perfect location. In 1986, Saddam’s workers blasted away Farhoud’s village and built an artificial hill in its place. Today, Saddam’s palace upon a hill stands on the same site where Farhoud went to school; from it, you can see reconstructed walls and mazes with perfect clarity. That beautiful view came at an immense cost. “I cried,” remembers Farhoud. “At that time, I felt like the village was a member of my family. I loved it.”

Nowadays, Farhoud waits daily outside the entrance to Babylon, where he works as a tour guide for hundreds of visitors from all over the globe. The gate, made from bright-blue bricks and polished off with a gold overlay, looks like it could have been transplanted from Vegas, or Disneyland*. Farhoud is now in his mid-50s, with a face worn by 25 years of working under the unforgiving sun. He has seen Babylon transform from an archeological site to the jewel of Saddam’s vanity projects—and then to an occupied territory under the Americans. Today, it seems to fall between picnic site and abandoned theme park. Teenagers wander among Saddam-era walls and Nebuchadnezzar-era bricks. They smoke cigarettes, steal kisses, and blast music from their speakers. The site belongs to a new generation now.

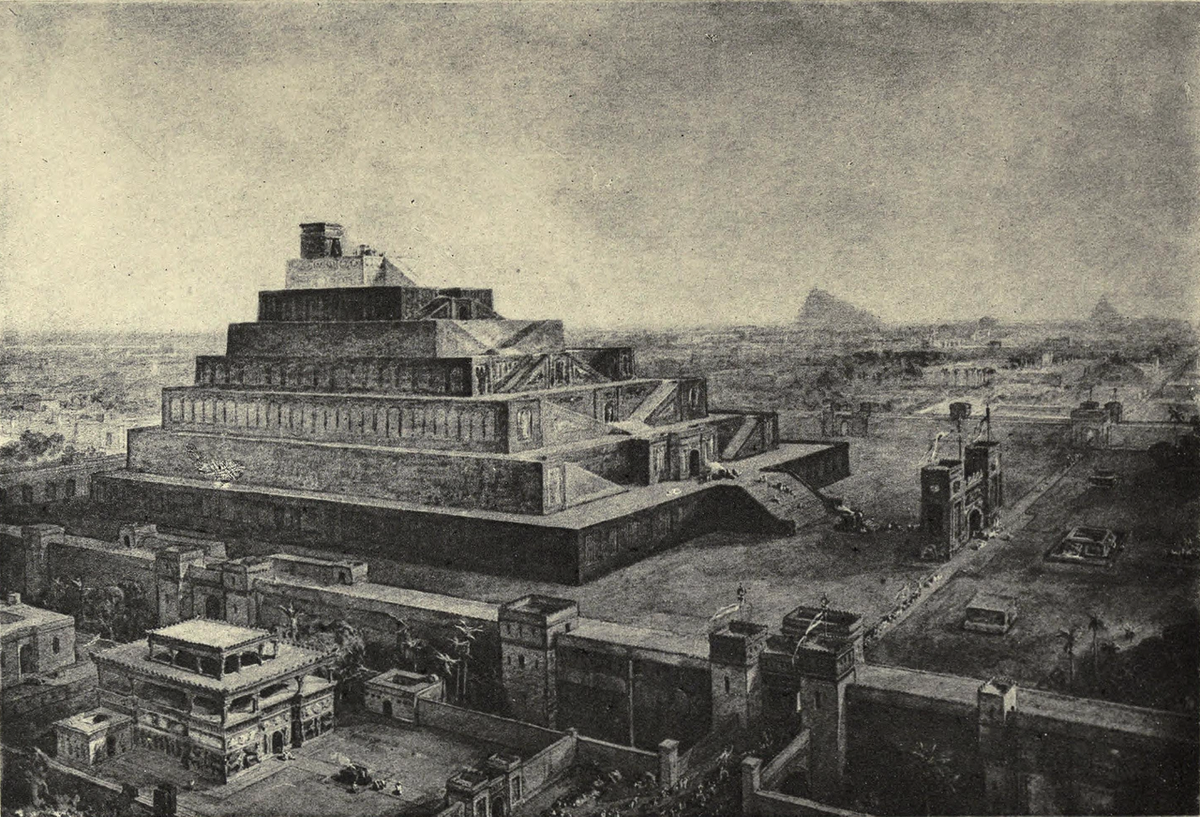

The ruins of Babylon, also known as Babel, date back over 3,000 years. The world’s first-known civil code was written here; Alexander the Great died here; countless Bible stories take place here. It holds an imagined as well as real presence in many people’s minds, which may be why so many rulers have tried to build their dreams here.

When Saddam invaded Iran in 1980, the country was still reeling from the 1979 revolution, and he believed a few weeks of fighting would solidify his position as the leader of a unified pan-Arabist dream. It proved to be one of the greatest political errors of his career. Farhoud, like many other Iraqis, was conscripted. Within a few years, Iran had not only retaken its territory, but also launched an offensive against Iraq. By 1983, the pan-Arabist dream was drawing thin. The war showed no sign of ending, and Iraqis did not understand why they were fighting in a conflict they never asked for.

To fuel support for the battle, Saddam turned increasingly turned to grand nationalist building projects. That was when he ordered the reconstruction of Babylon.

“Babylon is neither Islamic nor Arab—it is obviously deeply pre-Islamic,” says says Kanan Makiya, an Iraqi author and professor at Brandeis University who has written a book on Saddam’s building projects. “In celebrating Babylon and reconstructing the city of Babylon, what one is doing is essentially calling upon the idea of Iraq—not the idea of Arabism, or the idea of Baghdad as the spearhead of a new pan-Arabism in the region, or Islamism, but Iraq.”

Saddam siphoned millions into the rebuilding, and pushed to have the reconstruction built on the foundations of the original site. The project was not only nationalistic, but also narcissistic. “There was megalomania involved in that,” says Makiya. “Saddam wanted every Iraqi to know that he rebuilt Babylon. The point is that it’s not just an archaeological reconstruction of the city of Babylon for the sake of science and history and the past. It’s an idealization of that history for the purposes of the cementing of the legitimacy of the regime’s presence.”

His palace at Babylon is the clearest example of his hubris. It’s carved with Arabic calligraphy that at first glance resembles religious iconography, but upon closer appraisal reveals itself to be Saddam Hussein’s initials. Brutalist, hyper-realist reliefs depict him leading soldiers on the battlefield; the ceilings are painted with symbols of Iraqi civilization, ranging from Babylonian lions to towers that Saddam built in Baghdad.

When Saddam heard that Nebuchadnezzar had stamped the bricks of ancient Babylon with his name and titles, he ordered that the reconstruction mimic this practice. To this day, in the maze behind the Southern Palace, scores of bricks are stamped with a declaration: “In the reign of the victorious Saddam Hussein, the president of the Republic, may God keep him the guardian of the great Iraq and the renovator of its renaissance and the builder of its great civilization, the rebuilding of the great city of Babylon was done in 1987.”

The war killed hundreds of thousands of soldiers. When it ended in 1988, under a ceasefire brokered by the United Nations, Farhoud returned to a totally different Babylon than the one he remembered. Looking at the bright new cement bricks, he was aghast. “Saddam wanted to be like a king,” he says. “The building was not right.”

But Farhoud still loved Babylon. It was still the place where his father and grandfather had worked before him. He took up his job as a tour guide and welcomed crowds of Iraqi tourists, who marveled at what Saddam had built.

When President Bush ordered U.S. forces to invade Iraq in 2003, they occupied Babylon and turned Saddam’s castle into their command center. Their graffiti remains on the walls: notes of longing about faraway loved ones, reminders of soldierly protocol. The military also caused immense damage to the site, looting precious artifacts and running tanks over ancient ruins. Farhoud remembers that time with fury. “I would not sell a single piece for a $1,000,” he says, “Babel is more precious to me to me than my children.”

Farhoud says that the U.S. military arrested him in a broad sweep of Iraqi civilians and held him for two weeks in a sunless room. “I don’t remember the number of days in prison. I suffered from torture and I still feel pain today in my chest, because of the beatings from the Polish and American soldiers,” he says. Poland was one of only three nations whose soldiers joined U.S. forces in Iraq, as part of the so-called “coalition of the willing.”

But Farhoud doesn’t like to remember those days. Instead, he likes to tell stories of good days in Babylon. He met his wife within its walls, when she came for a visit in 1999. She was taking a tour with her family, and he says that as soon as he saw her, his heart started beating quickly and he knew he wanted to become close to her. His daughters, inspired by the site, are now studying archaeology and history at the University of Babylon. He loves Babylon with a fervor that burns through any dark memories he has of the place. “If I could, I would go without shoes here, because it’s a holy place,” he says.

Over 15 years after Saddam’s fall from power, his palatial tribute to the emperor has become a ghostly shell. Broken glass and graffiti are scattered through the once-grand palace halls. Teenagers and families smoke shisha and listen to music on Saddam’s vast balconies, overlooking the mind-boggling spread of Babylon.

From a balcony, Farhoud points out his favorite grove of date trees. He tells the story of the time he met Saddam in an entrance hall. He points out how the southern walls were constructed to confuse invaders. For all of the painful memories, he loves the city with naked affection. “I love Babel, and feel that Babel is like my father, mother, wife, brother, and sister,” he says.

In front of him stretches a vast maze, its walls engraved with the name of the ruler who once cast a shadow over this land–a man with the power to twist Farhoud’s home into a grand palace. He still loves this place. Its history is a poignant reminder that nothing built by men can last forever.

* Correction: A previous version of this story stated that Cinderella Castle is part of Disneyland. It is part of Disney World and Tokyo Disneyland.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook