Seeing the Pandemic Through the Shuttered Bungalows of an L.A. Sanatorium

Once a haven for tuberculosis patients, Barlow Respiratory Hospital is uniquely suited to the COVID and post-COVID eras.

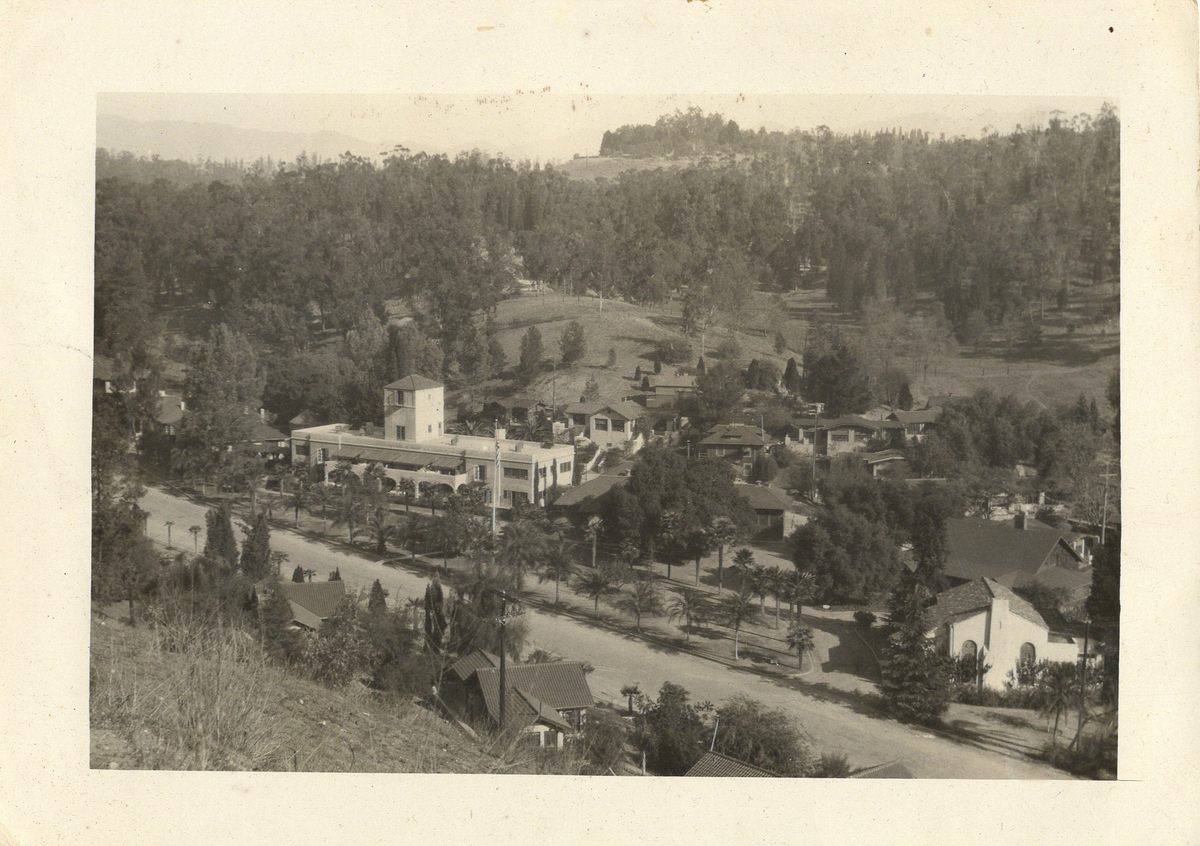

Just down the road from Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles, a row of boarded-up Craftsman-style bungalows marches down to a shallow green ravine, flanked by large, empty dormitory buildings. Along narrow walking paths, memorial plaques pay tribute to long-forgotten Angelenos who spent years of their lives at this place.

The bowl-like ravine holds one of the best-preserved sanatoriums west of the Mississippi. Founded in 1902 as a haven for people with tuberculosis (TB), Barlow Sanatorium flirted with irrelevance by the 1960s. As antibiotics transformed TB from a lasting malady into a more curable condition, sanatoriums like Barlow, which could host patients for years on end, were no longer necessary.

Today, Barlow’s campus—an entire time-capsule neighborhood—is full of reminders of the insular society that once thrived there: a lonely cluster of beehives, a scarred wooden coop where patients raised chickens, a black-barred aviary that now encloses a koi pond. But while the community may be gone, the institution has persisted, physically and philosophically merging past with present.

The main 1927 treatment building, where outdoor TB beds were once arrayed under Spanish-style arches, now houses the state-of-the-art Barlow Respiratory Hospital, which has perfected the delicate art of weaning patients with respiratory conditions from ventilators. Barlow’s specialty has given it high-profile status during the COVID pandemic—and its historical legacy offers fresh perspective not just on treating long-term respiratory illness, but also on meeting future infectious threats.

In the early 1900s, TB inspired the kind of fear that COVID-19 would a century later. Though scientists knew that the so-called “white plague” was caused by a rod-shaped bacterium that destroys lung tissue, no drugs existed to treat the disease, and it was killing Americans at the rate of more than 400 a day. “People were so scared,” says Soumi Eachampati, a former surgical ICU director at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. “The scale of TB devastation was incredible.” Around the country, sanatoriums sprang up with the twin goals of isolating infectious patients while putting them in open-air environments that were thought to promote recovery.

Physician W. Jarvis Barlow was committed to getting TB under control because he had suffered from the infection himself. After he was diagnosed in 1895, he headed from New York to San Diego and found that his symptoms improved. Crediting the sunny, dry climate, he was convinced that other patients could achieve the same result, and purchased a tract of land for his new sanatorium near Los Angeles’s Elysian Park. Barlow glad-handed local officials and philanthropists for the funds he needed to build and operate the facility.

When the sanatorium first opened, Barlow resolved to supervise the 34 incoming patients himself. He made daily rounds to patient cottages, either on horseback or by horse-drawn carriage, and a series of young, energetic nurses backed him up. While he was zealous about healing his patients, he was just as zealous about enforcing strict behavioral standards. “Patients must not discuss their ailments or make unnecessary noise,” an early-20th-century rules document read. “Lights out at 9 p.m. Cold plunge every morning; hot baths Tuesday and Saturday…. Patients disobeying these rules will be dismissed.”

This kind of regimentation helped make sanatoriums such as Barlow odd, closed, and sometimes stifling, societies unto themselves (not unlike our own homes during the COVID pandemic). The social encounters of the many bed-bound patients were confined to roommates, if they had any, and staff members who came and went. To prevent the spread of germs, patients used cheesecloth squares to catch their copious phlegm, then presented the makeshift handkerchiefs to be burned. When their more acute symptoms improved, doctors allowed them to get up and move around—and earn their keep. “Patients were required to work to earn their way once they were well enough,” says Julia Shimizu, Barlow Hospital’s director of public relations. “So they would be taking care of animals. They would be tilling the soil in the garden.”

If the epidemic-control measures the sanatorium adopted—quarantine and scrupulous sanitation—sound familiar, that’s because though simple, they proved effective. In the absence of more sophisticated measures or treatments, they mostly prevented patients from transmitting TB to family members or sanatorium staff.

But unlike most cases of COVID, TB was chronic, and could be contagious for a long time during active infection. That led to some draconian isolation measures. One pregnant patient at Barlow around the 1950s transferred to another local hospital to deliver her baby, but was immediately sent back to the sanatorium after giving birth to keep her child and others safe.

“She spent seven years here,” says Barlow medical director David Nelson, who has worked there since 1991. “Her contact with her child for seven years was that she would stand on the balcony on the second floor of the hospital, the other family members would bring the baby on the first floor, and they’d wave at each other.”After years of hospitalization at Barlow, the patient returned to her family and went on to lead a long, healthy life.

So dramatic was the impact of TB in midcentury that doctors went to extreme surgical measures as well. Among the most common interventions was an “artificial pneumothorax” procedure, a deliberate attempt to collapse a patient’s lung so that open “tuberculous cavities” would heal shut, keeping the disease confined to a smaller area while the patient’s immune system fought back. At times, doctors “would break a bunch of ribs and crush their chest to prevent the lung from re-expanding,” Nelson says. Though such measures sometimes worked to contain the disease, they could leave patients disfigured for life.

Despite—or in part because of—the sanatorium’s indignities and restrictions, many residents forged strong relationships with fellow patients, and worked hard to re-create a semblance of normal life. That push for community in isolation can be seen in the cottages across the street from the main hospital. Many feature broad open-air porches, which would have been ideal spaces to convene with others in recovery and reflect on the future. Multiple patients often lived in each cottage, forging college roommate–style bonds. (For years, Shimizu says, former Barlow residents trekked back to the campus for reunions with old friends.)

Though most of the cottages’ windows are now boarded up, spaces between the boards reveal intact time capsules of the sanatorium era. One cottage features a gleaming shower stall with vintage white subway tile and cross-handled water taps. Another has a perfectly preserved midcentury kitchen with whimsical floral-wreath wallpaper. A shallow serving dish still rests on the countertop, as if awaiting a meal.

The antibiotic revolution of the 1950s and 60s seemed to herald the end of long-term respiratory centers such as Barlow. Isolation and extended treatment for TB patients was starting to seem like a Victorian throwback, an extreme measure rendered unnecessary by medical advances. Yet the sanatorium’s management, showing its founder’s doggedness, settled on a pivot. “It is essential that Barlow continue to expand into the diagnosis, care and treatment of other chronic respiratory diseases,” medical director Fausto Tanzi argued in 1971, “if full use of the facilities is to be expected.”

As light streams into Barlow’s old library through a stained-glass angel portrait, the gift of an early-20th-century donor, Nelson reflects on how the hospital’s shifting mission set it up for a 21st-century pandemic. “When mechanical ventilation was invented, we chose that as one of our major focuses—taking care of patients who need prolonged ventilation on a respirator.” Over the past year, hundreds of the city’s COVID patients went on ventilators to stay alive. “That’s the type of patient we’ve been taking care of for all these years,” Nelson says. “When COVID happened, there were a lot more of those people circulating in the community.”

In line with Barlow’s vision, the hospital is taking a slow approach to healing these critically ill patients. Weaning someone off of a ventilator is like balancing a coin on its edge. Doctors first gauge what is known as a patient’s “liberation potential,” their likely ability to breathe without the machine. Then they carry out spontaneous breathing trials to make sure patients will get enough air after the ventilator tube is removed. Overestimate liberation potential and you risk doing further damage, setting the patient’s progress back.

What’s old is, in some ways, new again. CEO Amit Mohan hopes to bring Barlow even closer to its roots, providing long-term, bespoke respiratory care—the norm a century ago, an outlier now—to the pandemic era, even for patients who lack private insurance. Once severe COVID patients relearn how to breathe, they can face a daunting new set of challenges: physically and socially readapting to the world after months in the cocoon of illness.

The outset of the COVID pandemic, when we were all sequestering indefinitely—drawing tightly closed societies around us like cloaks—was a simulation of the sanatorium era. Now that we have highly effective COVID vaccines and the impulse to isolate has receded, at least in the United States, the stakes, the need for collective action, and the path through possible future pandemics are clear. COVID “will certainly serve as a wake-up call that this thing did happen to us, even though we think of ourselves as a very advanced civilization,” Nelson says. “We tend to feel that we’re immune to these kinds of things. But obviously, we’re not.”

Publicly funded, sanatorium-style isolation centers could serve as a low-tech bridge to stop the spread of a future pandemic before a vaccine can be broadly distributed, just as they did when TB was at its most widespread. India is already testing this concept by creating dedicated “COVID hospitals,” some of which are repurposed TB sanatoriums.

“Health experts and policymakers need to appreciate [the] age-old concept of sanatoria for prevention and treatment,” three doctors from India wrote in a recent letter to the editor of the International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health. “The threat of other biological warfare and emerging diseases is always there…. Isolation remains a key measure to prevent transmission.” (Not to mention that TB, too, has refused to stay down: The current vaccine has limited effectiveness, latent infection is almost total in some parts of the world, and antibiotic-resistant strains are widespread.) But the trauma surgeon Eachampati points out that for people to accept isolation-based containment strategies in the United States, they would have to reclaim a sanatorium-era sense of communal obligation. “After World War II and in the 50s, people were very unified—‘What’s best for the country is best for me.’ You need full buy-in.”

Today at Barlow, orange cones surround the main hospital building. A major renovation is underway, which will keep the 1927 building open while a new one is constructed around it. (Due to a lack of restoration funding, the sanatorium dorms and bungalows will remain in their current state for now.) W. Jarvis Barlow would have been pleased with the institution’s progress, as he pictured his facility outlasting him by generations. “He was living in an entirely different world,” the public relations director Shimizu says, “and he imagined there would be ongoing needs beyond what he could envision at that time.” Cracked ribs and burnt handkerchiefs are relics of the past, but now we can see how a set-apart sanctuary where patients can recover at their own pace feels more like the future than ever.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook