The 18th-Century Quaker Dwarf Who Challenged Slavery, Meat-Eating, and Racism

Benjamin Lay is not to be overlooked.

One Sunday, 18th-century Quakers living in Abington, Pennsylvania, near Philadelphia, were met with a strange sight outside their morning meeting. The snow lay thick on the ground and there was Benjamin Lay, a member of the congregation, wearing little clothing, with his “right leg and foot uncovered,” almost knee-deep in the snow. When one Quaker after the next told him that he would get sick or that he should get inside and cover up, he turned to them. “Ah,” he said, “you pretend compassion for me, but you do not feel for the poor slaves in your fields, who go all winter half-clad.”

Lay always cut a striking figure. An 1818 article, republished in the newspaper The Friend in 1911, many years after his death, described him thus:

… only four foot seven in height; his head was large in proportion to his body, the features of his face were remarkable … He was hunch-backed, with a projecting chest, below which his body become much contracted. His legs were so slender, as to appear almost unequal to the purpose of supporting him.

His act of protest in the snow is of the sort that might make the news today, but in the 1730s it would have been radical almost beyond understanding. This was a time, writes Marcus Rediker in his recent book The Fearless Benjamin Lay: The Quaker Dwarf Who Became the First Revolutionary Abolitionist, when “slavery seemed to many people around the world as natural and unchangeable as the sun, the moon, and the stars in the heavens.” Lay was an abolitionist, vegetarian, pacifist, gender-conscious, anti-capitalist, environmentalist Quaker, with dwarfism and a hunchback, and he wanted to change the apparently “natural” order of things.

Despite his ultra-radical leanings, Lay has been almost entirely excised from modern history books. “The wildness of his methods of approaching antislavery is part of it,” Rediker says. “He was extremely militant and completely uncompromising.” This level of abolitionist militance was unprecedented, and only began to become common after the 1830s. Lay sits outside of the standard narrative of the movement, and his disability and lower socioeconomic status make him difficult to place in a clear historical model. “He just didn’t fit the story,” Rediker says.

The snow protest was by no means Lay’s only performed, dramatic, nonviolent act of radicalism. Quaker neighbors of his kept a young “negro girl” as a slave, and continued to justify the practice, even in the face of his exhortations on both the evil of slavery in general and the “wickedness” of separating enslaved children from their parents. When the neighbors refused to listen, Lay invited their six-year-old son into the cave where he lived and innocently entertained him throughout the day. The boy’s parents panicked. The Village Record, a local newspaper, later described how Lay “observed the father and mother running towards his dwelling; as they drew near, discovering their distress, he advanced and met them, enquiring in a feeling manner: ‘What is the matter?’” The parents, understandably terrified, explained that the boy had been missing all day. Lay is said to have paused, and said: “Your child is safe in my house, and you may now conceive of the sorrow you inflict upon the parents of the negro girl you hold in slavery, for she was torn from them by avarice.” Taking the Bible as his model, he seems to have generated living parables to show people the evil of their ways. (Another version of this story claims that the child was a three-year-old girl.)

Lay seems to have had big dreams and ideals to match. Born to a family of common Quakers in Colchester, England, he left his work as a glover at 21, eschewed his likely inheritance, and went to London in pursuit of his fortune. There he became a sailor, desperate to see the world despite the risk of injury or death. (That year, 1703, as many as 10,000 British sailors and crew members lost their lives in a major cyclone.) For more than a decade at sea, he slept in a hammock and lived among people of all ethnicities, shapes, and sizes. For the rest of his life, even after years on land, Lay thought of himself in some sense as a sailor. “At the end of his life,” writes Rediker, “he made a request that shocked his friends and acquaintances: he asked a man to ‘burn his body, and throw the ashes into the sea.’”

It was on his voyages that Lay first became aware of slavery. Fellow sailors told him horror stories about working in the African slave trade, where hundreds of thousands died in transit. Still a devout Quaker, Lay began to connect these practices to Biblical verses about racial equality—that God “hath made of one Blood all Nations of Men for to dwell on all the Face of the Earth.” He soon concluded that slave traders were murderers, and that the practice was barbarous.

In time, Lay married. Like him, his wife Sarah was a Quaker. She had similar physical conditions, and shared many of his forward-thinking beliefs. The Lays moved, in 1718, to Barbados, a place with some vestiges of a Quaker community. They were appalled to find themselves on an island built on slavery, “barbary and ill-gotten gains,” where slaves were treated worse than horses. The Lays held open meetings and offered meals to the island’s enslaved population, which drew the opprobrium of the island’s white population. Though the Lays had already made plans to leave, these “Masters and Mistresses of Slaves” called for them to be banished. In 1720, they returned to England. Lay was just getting started ruffling feathers in Quaker communities.

Twelve years later they moved to Pennsylvania, where they established themselves in the local Quaker community again. Lay was shocked to find slavery a common practice there, too, after more than a decade in England, where it was rare. At that time, around 10 percent of Pennsylvanians were enslaved, compared with around 90 percent in Barbados. In Pennsylvania, Lay performed some of his most dramatic protest stunts, including disrupting Quaker meetings with abolitionist messages. He is said to have stood up in meetings whenever a slaveholder attempted to speak, and shout: “There’s another negro-master!” Three years later, Sarah died, unexpectedly. Lay was heartbroken.

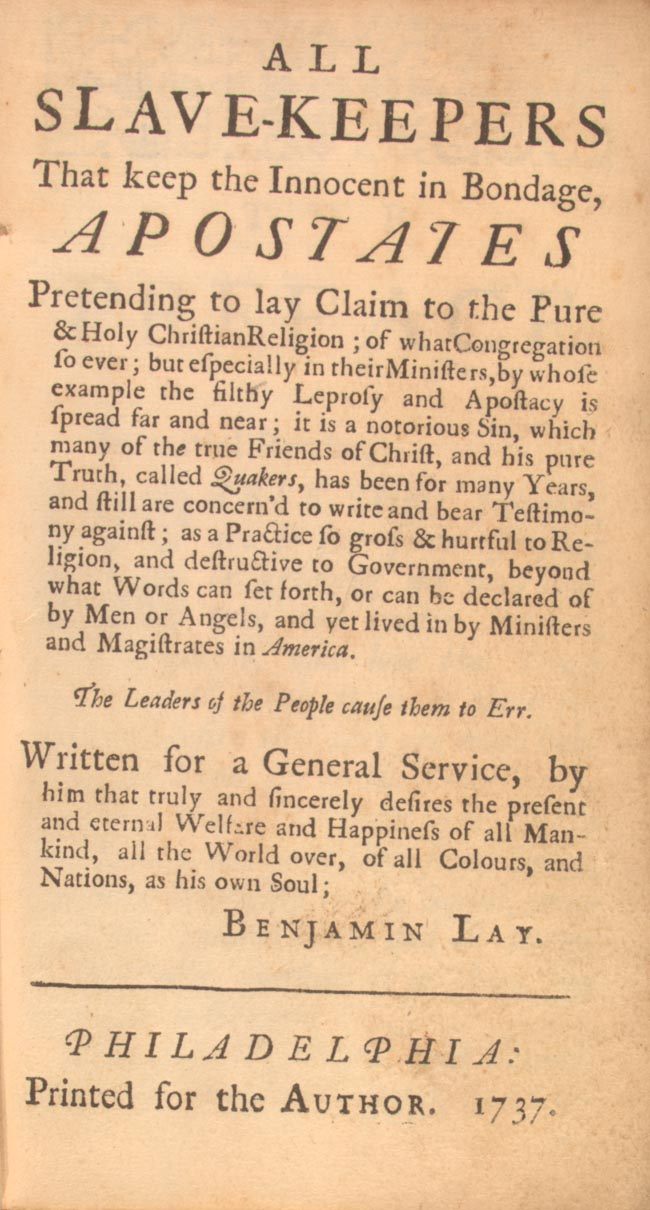

By the time he himself died, in 1759, Lay had eked out a strange and deeply principled life for himself in the Philadelphia area. He lived in a cave, made his own clothes, and walked everywhere. He had become a vegetarian and felt that animals, including horses, should not be exploited for their labor or their meat. In 1737 he published the revolutionary tract All Slaveholders That Keep the Innocent in Bondage, Apostates, a mixture of polemic, musings, and autobiography, put together in a curiously nonlinear, almost postmodern, format. (The publisher—Benjamin Franklin, a longtime, if a little wary, friend—chose to keep his own name off the text.) Despite his requests to be cremated, which would have been tantamount to paganism, Lay was buried in an unmarked grave close to his wife’s, in the Quaker burial ground.

During his life and after his death, many people, Rediker says, thought of Lay as deranged. “[Historians] thought he was not sane, and this was a very effective way of putting him at the margins.” Ableism, too, seems to have factored in this general unwillingness to take him seriously. But some of those in the abolitionist movement did feel the need to celebrate this “Quaker comet,” as he came to be known. Benjamin Rush, one of his earliest biographers, said Lay was known to virtually everyone in Pennsylvania; his curious portrait was said to hang in many Philadelphia homes. This early abolitionist burned bright, and, despite his exclusion from many abolitionist narratives, refuses to be extinguished from history.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook