The Woman Who Made Black Traditions a Vital Part of Music Education

Singer Bessie Jones is the reason so many American children know the folk songs of African and Gullah cultures.

It’s early afternoon on a weekday, and school is in session. A classroom of second-grade students rises to their feet and hurriedly clasp hands with one another, their teacher joining in to form the strand of children into a circle. She turns her toes to the left, and gently urges the ring to start moving clockwise, as she sings, “walk Daniel, walk Daniel…” The students begin to sing along, their feet marching to the rhythm on the worn carpet. The teacher continues: “fly Daniel”—some children spread their arms wide like soaring airplanes, while a few rapidly flap their fingers to mimic birds. They sing several more rounds of “jump Daniel,” “dance Daniel,” “skip Daniel,” all while keeping their circle rhythmically rotating. After many giggle-strewn minutes, they finish with “sit Daniel,” and the students sing their way into their seats to continue with their music class.

“Walk Daniel” is just one of the many songs from Black cultures that has been taught by music educators in classrooms for over half a century. These folk songs and games are used to teach musical concepts in a playful manner, all while providing students a deeper cultural understanding than any rote history lesson could provide. The large and important place Black music holds in modern education is due in no small part to the life and work of Bessie Jones, a Black woman born into poverty in the rural South at the turn of the century who used her voice to break down racial barriers in education, while forging an undeniable space for Black traditions to exist in perpetuity.

Mary Elizabeth “Bessie” Smith Jones was born on February 8, 1902, in Smithville, Georgia, and raised in the nearby community of Dawson by her mother, stepfather, and various members of her extended family. They lived in rural conditions and faced considerable poverty, necessitating Jones start working as a young child to supplement the family’s income. Her attendance at school was sporadic, and after her stepfather passed away in 1911, she left entirely to work full-time. She held various domestic and agricultural jobs, and though only a child herself, was primarily employed as a nursemaid and caretaker to the children of affluent white families. Jones gave birth to her own daughter, Rosalie, at the age of twelve, after marrying her first husband, Cassius Davis, in 1914.

Music was always a part of Jones’s life. Nearly all her family members were musically inclined; her step grandfather, Jet Sampson, was a formerly enslaved man with marked singing talent and a gift for storytelling. He taught Jones many of the African American folk songs, work songs, and spirituals she’d carry with her throughout her life. Various members of the family played banjo, guitar, accordion, autoharp, and even took to crafting their own wooden instruments. Her husband Cassius hailed from a family of vocalists in Georgia’s sea islands, a place that would later hold great importance in Jones’s life. Jones and her family were active participants in local churches, where she learned and committed to memory numerous hymns, schoolyard songs, and plays.

In the long days Jones spent working, she made these songs and plays integral to life. She regarded them as a natural and necessary part of caring for children, stating in the liner notes of her album Get in Union, recorded between 1959 and 1966, “I remember a hundred games, I suppose…We had all kinds of plays…we would hear all those [songs]-riddles and stories…And then I has a great remembrance of those things.”

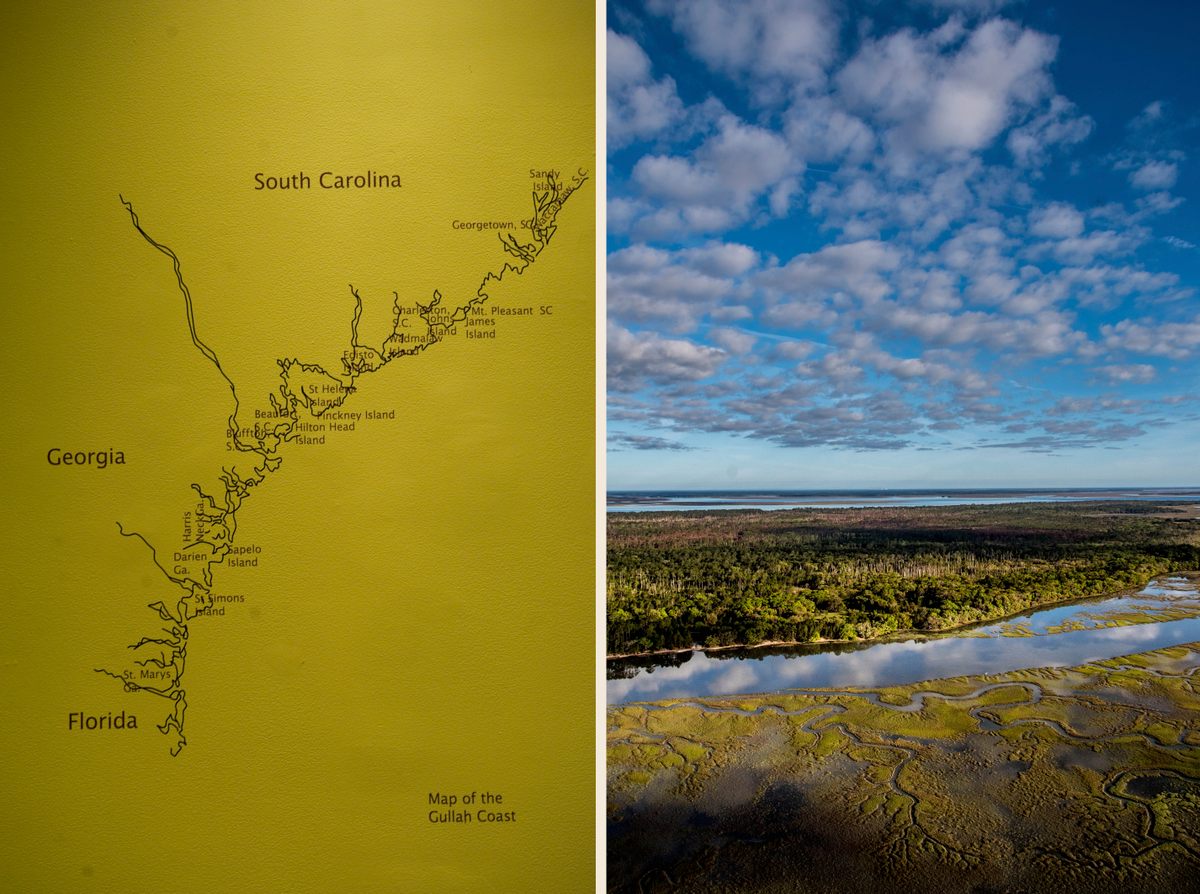

In 1926, when Jones’s husband Cassius became ill and passed away, she set out for Florida in search of higher paying work. While working as a cook on a farm in 1928, Jones met and married her second husband, George Jones. Together they spent the next seven years traveling up and down the East Coast as migrant farm workers, before settling in St. Simons Island, Georgia. Here Jones joined the Spiritual Singers Society of Coastal Georgia, a vocal ensemble dedicated to preserving the musical traditions of African and Gullah cultures.

Years earlier, the Singers Society had caught the attention of Alan Lomax, an ethnomusicologist at the helm of the twentieth-century American and British folk revivals. Throughout his lifetime, Lomax captured thousands of field recordings across the United States, Europe, and the Caribbean, collecting a treasure trove of folk traditions. When he returned to St. Simons Island to record with more modern equipment in 1959, he met Bessie Jones. Following that session, Lomax recruited Jones and a handful of other singers in the group to take part in a film he was making about the early colonial period in Williamsburg, Virginia.

While in Williamsburg, Jones experienced the onset of her “call to teach,” saying, “it’s great to me when I’m singing and can think to myself that I’m singing something I need to sing…that my old foreparents and the other folks of the tribe along in those days knew…I believe they would be rejoicing.” From that moment forward, Jones worked to answer her calling.

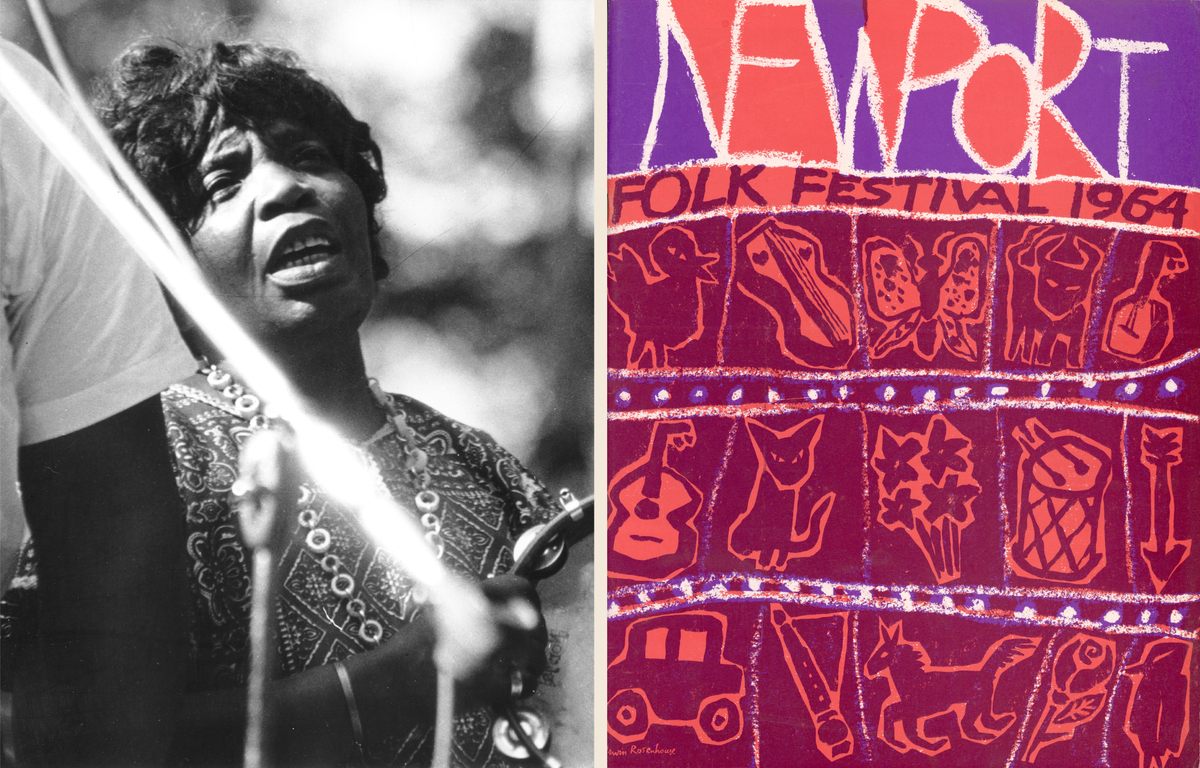

Alongside Alan Lomax, Jones spent the better part of the next two decades teaching and speaking around the United States, offering workshops on Black musical tradition to both children and adults. She taught while regularly performing with the Georgia Sea Island Singers, a group she’d formed in 1963, making appearances at such notable events as the Newport Folk Festival and the Poor People’s March on Washington.

In 1972, with the assistance of Lomax’s sister Bess Lomax Hawes, a selection of Jones’s materials was published under the title Step It Down. Jones presented on the usefulness of these songs and games for teaching children at the Kodály Musical Training Institute in Watertown, Massachusetts—Kodály being a widely practiced philosophy of music education that emphasizes singing to cultivate musicianship, cultural belonging, and personal identity—among other conferences. Her teachings soon spread to classrooms across the nation. In the foreword of the book, Hawes says, “Step It Down will keep [Bessie Jones] alive for generations of children and teachers yet to come.”

Indeed, it has done just that, as Jones’ work has grown only more integral to music education in the years since passed in 1984. Of her enduring impact, musical scholar Mary Jo Sanna Barron says, “she made one feel a part of the human community that reaches from the past into the future.” Songs recorded by Jones have even made their way into popular culture, appearing in iconic shows like Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. Step It Down continues to be a part of most teacher training programs today, and children around the country sing the songs, play the games, and listen to the stories Jones collected throughout her lifetime. Through these materials they learn the rudiments of music theory, deep cultural traditions, and an alternative perspective on American history.

But to the children such merits are secondary. In their experience, they are simply enjoying the act of singing and playing with one another, just as Bessie Jones intended.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook