The Women Behind the First Black Music Magazine

In the late 19th century, “The Musical Messenger” had a message to send.

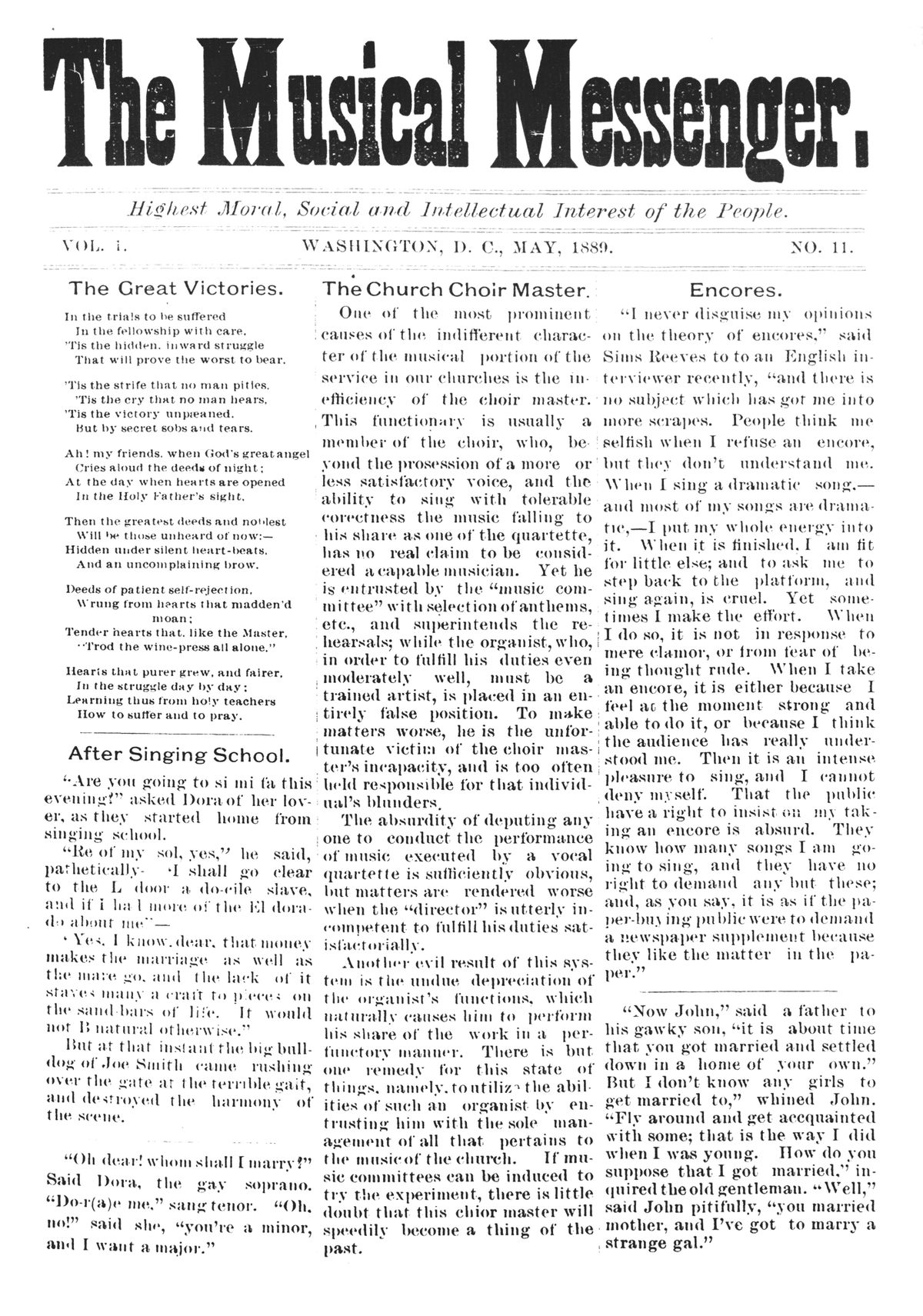

Today, so far as anyone knows, there are just two surviving issues of The Musical Messenger. It was and is a groundbreaking publication that ran from 1886 to 1891—and by all accounts the very first Black music magazine. All that stands between remembering and forgetting are just those two issues in the Library of Congress, one four pages, the other three. Whole movements, plans, and ideas rest on those seven pages from 1889. History isn’t a straight line, but it isn’t a stretch to link The Musical Messenger to any number of Black-owned and -run publications. Ebony. Freedomways. Vibe. Each is a link in a chain that was started by Amelia Tilghman, a musician and educator from Washington, D.C.

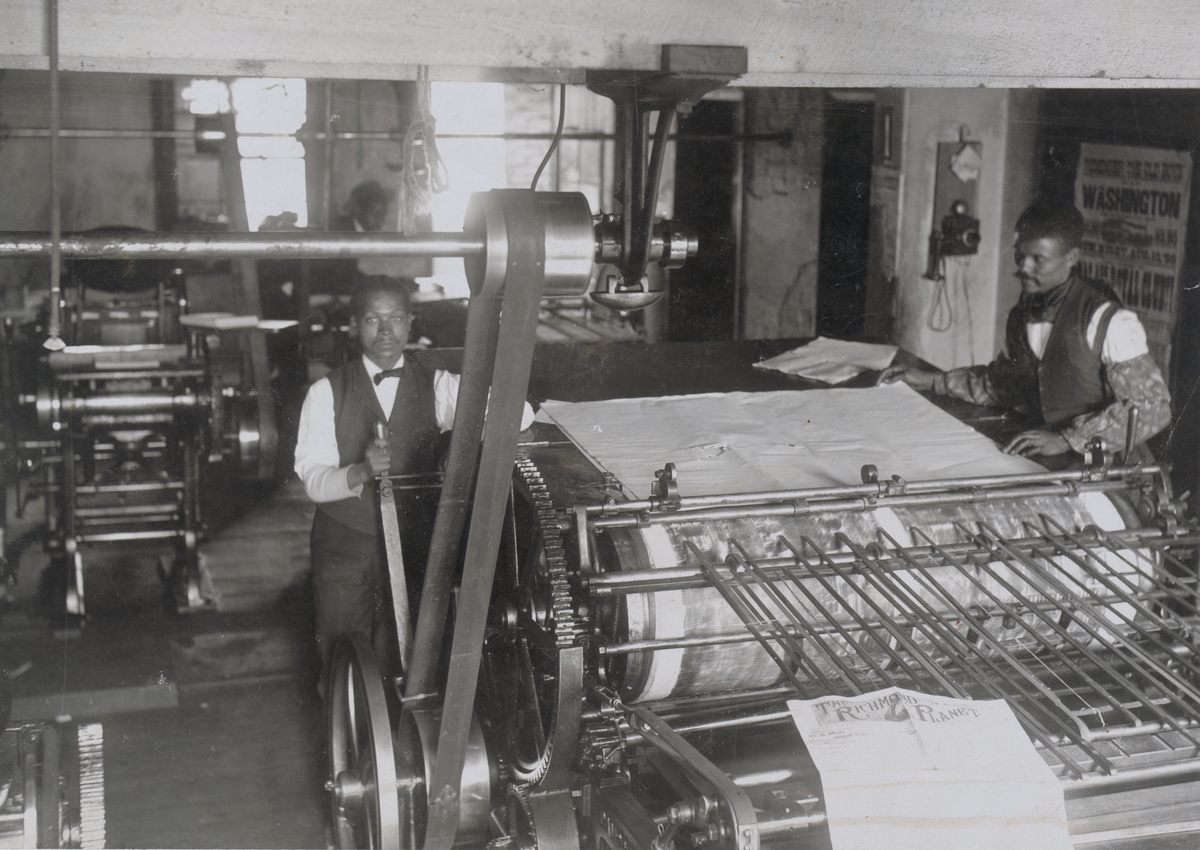

Though Tilghman’s magazine was the first of its kind, it was hardly the first example of Black journalism in America. Before emancipation, there were publications such as Freedom’s Journal—the first Black-owned and -operated newspaper, launched in 1827—and The Anglo-African, which represented both news and a voice of the abolitionist movement. “Newspapers held a very important role in Black communities,” says New York University historian Elizabeth McHenry, who specializes in Black print culture. “[They made] readers feel like they were in community together.”

There was art coverage in those pages, too, which may seem unusual at first glance. When freedom itself was the primary subject, how could music or art feel vital and important? “People accused Black people of having no culture, and devalued Black art forms,” says McHenry. “So claiming and showing that they appreciated music was an important means of claiming a space in American society.” An article in an 1827 issue of Freedom’s Journal, for example, highlighted the intersection of music and humanity in a review of a concert of sacred music: “The ignorant and prejudiced may laugh at the idea of a Concert of Sacred Music being got up by Africans. We know that their laugh is the laugh of fools, whose derision shows their ignorance, and whose mockery their folly.”

In addition to reviews, papers such as Freedom’s Journal also contained ads for concerts, music schools, and sheet music. Music has always been an important part of Black life, and its inclusion in the newspapers showed readers, both Black and white, that freedom could take many forms. Of course, most important was actual freedom from the horrors of slavery and, later, the restraints of segregation. But the freedom to love art, to sing and play beautiful music, to sit for hours listening to notes floating above—that was freedom, too, the freedom to experience joy. In The North Star, a paper founded by Fredrick Douglass, a concert review explained: “Now, is it not too bad that ‘colored folks’ should dare to love music, and to have the same emotions common to white folks? … Ought colored people be allowed to feel just like white folks? … Ought not a colored man to be worth two hundred and fifty dollars, in real estate, before he ventures to love music equally with white American citizens?”

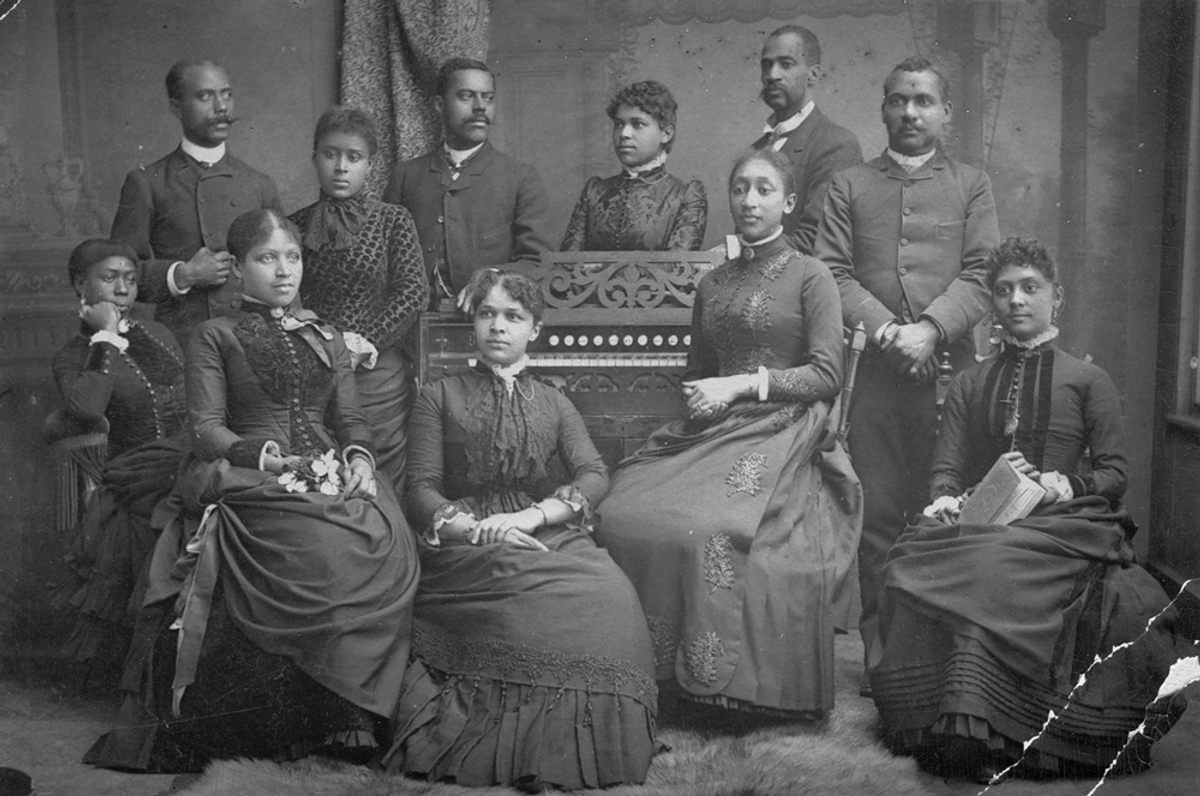

This is the world Tilghman inherited, a world that understood that, in its own way, art was humanity. “To be associated with the arts, with literature and with intellectual and political discussion, was a way of claiming that world as their own,” McHenry says. Tilghman was born in 1856 to a middle-class family in Washington, D.C., and graduated from Howard University in 1870 with a teaching degree. She was also well known for her musical work. A profile of her in the 1893 book Noted Negro Women and Their Triumphs, praised her “vocal talent,” which “has at all times won for her the greatest praise both from public and press.” After she toured throughout New York State, local press dubbed her “The Queen of Song.” She later performed with the Washington Harmonic Musical Concert Troupe as lead soprano. An accident curtailed her music career, but her second act was just around the corner and a bit farther south.

Tilghman moved to Montgomery, Alabama, and started teaching, and occasionally still performing. She also moved in circles that had freedom on their minds. It was in Alabama that she started The Musical Messenger, though, at some point, operations moved to Washington, D.C. The move to journalism didn’t come out of nowhere; Tilghman was a seasoned writer, having served as a correspondent for Our Women and Children, a magazine published from 1888 to 1891, which was a venue for many Black women journalists at the time, including Ida B. Wells. But as any dedicated music nerd knows, when you love something so much, it’s never far from your mind. The Musical Messenger was a way to share that love, and her love for Black people. The magazine had two purposes: to provide the musical news of the day, and to advocate for equality. The pages of The Musical Messenger were a reflection of Tilghman herself, and that extended to the paper’s staff.

The masthead of The Musical Messenger is a thrilling thing. The two boldest names were women. Tilghman held the lead role as editor alongside Lucy Bragg Adams as associate editor. Adams was every bit as accomplished as Tilghman, a noted musician, composer, and writer, with work appearing in the A.M.E. Review and, like Tilghman, Our Women and Children, among other publications. She had come from a prominent Black family, and her brother, George, was also a well-known journalist and activist. Music historian Juanita Karpf speculated in a 1997 article for International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music, “It seems plausible that the addition of the Bragg family name to the masthead of the Musical Messenger, an unimpeachable and enduring name in the African American community of her day, ultimately contributed to the longevity of the paper.” The addition of staff writer Victoria Earle Matthews, another prominent journalist and activist of the era, also signaled that the paper was concerned with more than songs and performers.

A reader, or better yet a subscriber ($1.00 per year), of The Musical Messenger could expect to read about the major goings-on in the music community—performance schedules, concert reviews, tips on music instruction—along with features on historic moments in music, such as the role of music during wartime and short biographies of composers such as George Frideric Handel and Joseph Haydn. Other articles were pointedly and explicitly about politics and race. Some of these definitely leaned more toward shaming than uplift, such as “Colored Loafers: To the Young Colored Men of America,” which accused jobless Black men of “sinking the race.” Others felt a little softer, gentler.

An untitled article in the July 1889 issue encouraged readers to keep moving forward, to keep striving, no matter the odds. “The man or woman who stumbles and yet does not fall, will make better headway for himself and humanity,” it read. Jokes sat alongside prayers and obituaries and a column called “A Musical Mugwump” that complained about “the well-meaning but foolish young persons” who Italianized their names just because “they expect to sing in Italian opera.” It was never one thing, but rather a reflection of all of the many ways that Black people could express themselves and reclaim their history and culture.

Black music at the time, and for decades afterward, often erased Black people. White listeners then loved the sounds of spirituals and folk, but needed it to come in the right package. That often meant blackface. Black composers were working in the late 1800s to early 1900s, but they were often relegated to producing music that sold, and that was minstrelsy, caricatures and stereotypes set to music. The Musical Messenger was what it looked like to push back against that by highlighting singers, musicians, and composers who rejected it.

There was nothing like The Musical Messenger before that moment. “People have pointed to the richness of segregated black communities, rather than only lamenting the fact of segregation,” says McHenry. “Black newspapers have a long history of bringing people together, speaking to and for them, [and] establishing community norms.” The Musical Messenger was, in its way, forming a community around music, not so different from fans who dance shoulder to shoulder in sweaty clubs, record collectors digging for sonic gold, or music lovers poring over liner notes. From sheet music to the ghostly notes on a worn 78 to the clarity of digital music, every note is a plea to be heard. Tilghman heard her people, and wanted the nation to hear them, too.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook