Can Science Ever Make A Real Diamond?

The battle to define what constitutes the world’s most famous gemstone.

This machine that analyses and measures the spatial, 3-dimensional properties of the diamond and then drops them into a program akin to CAAD, which determines the design the cutters can cut on it. (Photo: Jake Stangel)

It doesn’t look like the entrance to a paradigm-shifting, potentially world-changing start-up, but there it is: an unmarked door, facing out of a low-slung beige building on a street lined with tune-up shops. Inside, the scene is equally unassuming. There’s a man wearing black gloves, seated in front of a box about the size of a passenger van that’s blasting an ominous ommmm.

Welcome to California’s shiniest new diamond mine.

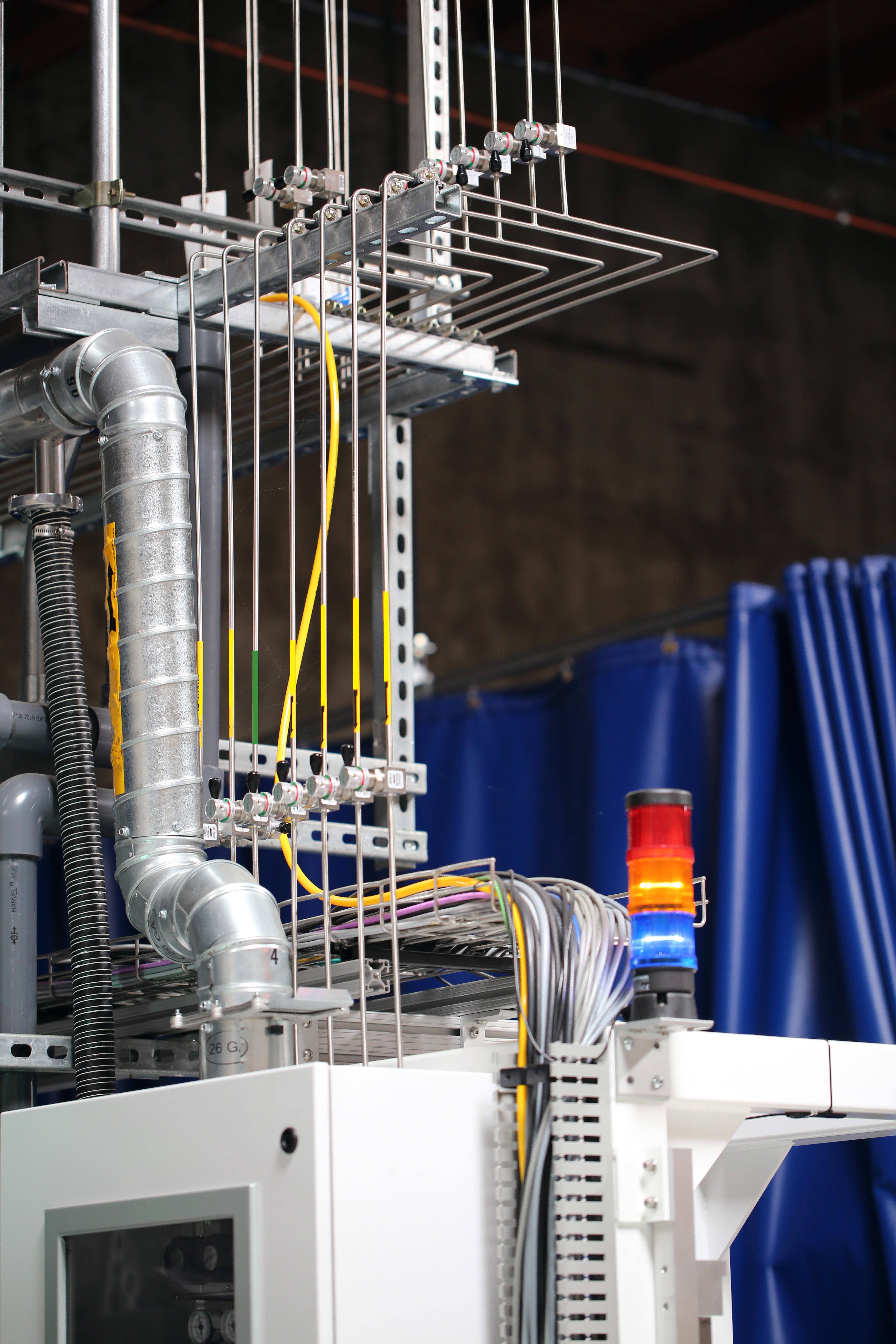

From the other end of the room, Martin Roscheisen, Diamond Foundry’s CEO, is explaining what, exactly, is going on here. That box is called a growth reactor, he says. Basically, it’s an atomic oven. Inside, a tiny diamond, known here as a “seed diamond,” sits waiting to be blasted with hot plasma. The reaction will cause the crystal latticework of the diamond to extend. In other words: From this seed, a new diamond will start to grow.

“They grow slowly, atom by atom, and there’s about one quadrillion atoms per layer,” Roscheisen shouts over the din. “So it’s a slow-growth process.” By slow he means two weeks, which is how long it takes the Silicon Valley–based company to hot-forge jewelry-grade diamonds identical to those the earth takes eons to mete out.

Part of the foundry’s reactor. (Photo: Courtesy Diamond Foundry)

Roscheisen is lanky, with a boyish face and clear plastic glasses. He has a surprisingly honkish laugh, which he lets out when asked whether he likes to check on his diamonds “like muffins in an oven.” (Answer: He does. The reactor has a window.)

Diamond Foundry launched to exuberant press last November, promising to “reimagine the diamond industry.” It’s an industry that is notorious for environmental and human rights abuses, most notably in Africa, where our lust for diamonds has fueled civil wars in seven countries, leaving millions dead, maimed, or displaced. “This is fundamentally about creating a better choice,” Roscheisen says. “Our product is a better diamond in every way. It is materially pure. It is ecologically pure. It is made in America.”

The Foundry’s machines are helmed not by child laborers but white-collar professionals. These are eco-friendly diamonds (even the energy required to create them is offset by the purchase of solar power credits), yet they’re atomically identical to nature’s gems. It’s an achievement Maarten de Witte, one of Diamond Foundry’s master cutters, describes as “beyond the dreams of the ancient alchemists of turning lead into gold.”

Martin Roscheisen, Diamond Foundry’s CEO. (Photo: Courtesy Diamond Foundry)

But the company faces an uphill battle if it’s to realize a world with no diamond mines. Convincing people to wear man-made diamonds is one thing. There’s also the very profitable industry built around mined diamonds (this year, Bloomberg reported that sales hit $79 billion worldwide), which means that man-made diamonds are banned from the world’s largest diamond trading floor, in Israel. “They don’t fit in our stores,” Mark Aaron, vice president of investor relations at Tiffany and Co. told The Wall Street Journal in 2007. “Natural diamonds fit in our stores—diamonds that come out of the ground.”

So even if Diamond Foundry has achieved the seemingly impossible, the real alchemy is just beginning. It has nothing to do with the perfect alignment of atoms, but rather, decades of seductive advertising. Can it convince consumers that a weeks-old diamond baked in a machine is just as valuable as a billion-year-old stone?

Close-up of a diamond produced by Diamond Foundry. (Photo: Courtesy Diamond Foundry)

Man-made diamonds might sound hypermodern, but the science was actually decoded in 1954 by H. Tracy Hall, a GE chemist who earned just a $10 savings bond for his discovery. Any diamond, whether it originates below ground, above ground, or in outer space1, is made of carbon. Natural diamonds are formed 100 miles below the earth’s surface, where temperatures hover above 2,000°F. There, carbon is crystallized by immense heat and geological pressure before the gems rocket to the earth’s surface by way of volcanic flues.

Historians estimate that the first diamond mines were established as early as the 4th century BCE in India, where the stone was revered for its strength. Over two millennia later, that strength sparked a technological arms race to synthesize the gem. After World War II, there was a global shortage of industrial diamonds, a key component in making the tools that build everything from munitions to subway tunnels. Hall was part of the team behind a GE mission called Project Superpressure, which succeeded in creating a press powerful enough to mimic the geological forces acting on carbon deep within the earth.

The process, known as high pressure, high temperature, involves sandwiching graphite between a natural diamond and a metal solvent, heating the press to above 2,552°F, and applying pressure. The melting metal acts as a catalyst, forcing the graphite to crystallize atop the diamond.

A second process, called chemical vapor deposition (CVD), was later developed, in which carbon-rich gases are combined with hydrogen in a chamber and exposed to enormous levels of heat. The gases react, causing carbon atoms to hitch onto the “seed” diamond.

Inside the plasma reactor at Diamond Foundry. (Photo: Courtesy Diamond Foundry)

The first jewelry-grade man-made diamonds weren’t created until the 1970s. And only in the last decade have manufacturers produced stones rivaling those found in nature. Roscheisen says it took his team three years and five generations of reactors before they were able to efficiently produce the gems. Their process remains a tightly held secret, but the Gemological Institute of America, the world’s top diamond-grading body, identified two samples submitted by Diamond Foundry as CVD diamonds.

“I really don’t think they have a fundamentally different technology from other CVD producers,” Wuyi Wang, the GIA’s director of research and development, says, though, he explained, the Foundry might have modified the process to grow more crystals at faster speeds.

Other diamond manufacturers around the world make similar claims about stone clarity and technological improvements, so, technology aside, how is Diamond Foundry different? With famous billionaire investors—including Internet glitterati like Evan Williams of Twitter, Alison Pincus of One Kings Lane, and Andreas von Bechtolsheim of Sun Microsystems, as well as Leonardo DiCaprio, who starred in the movie Blood Diamond—it may be the first grower with sufficient brawn and e-commerce savvy to revolutionize the diamond market and pull off the impossible: to convince consumers a man-made diamond is “forever,” even if it’s only day-old.

The Kimberley diamond mine in South Africa was operation from 1871 to 1914, also known as the ‘Big Hole’. (Photo: Vladislav Gajic/shutterstock.com)

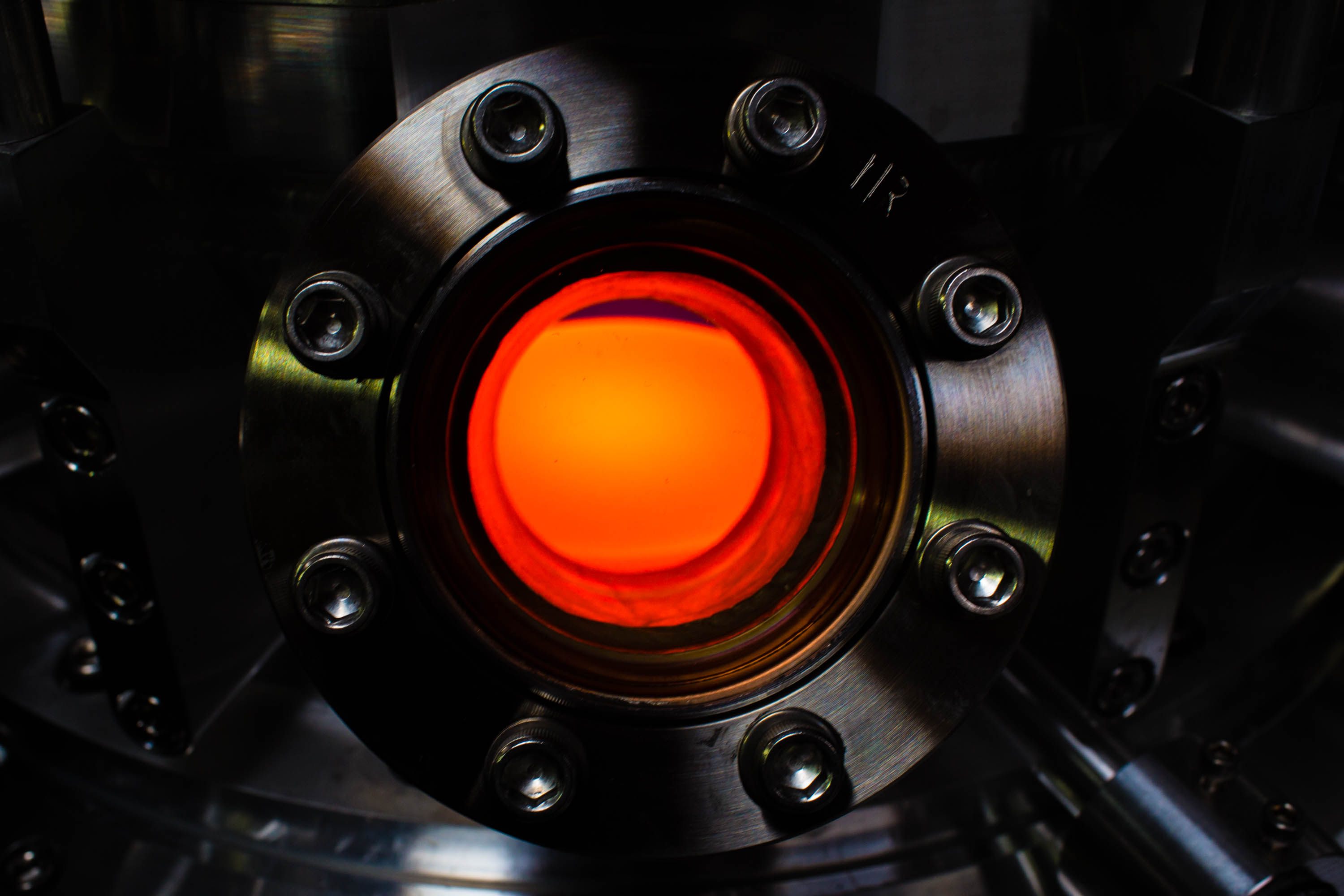

On the market, a diamond is much more than a metastable allotrope of carbon—it’s everlasting love. And credit for that goes to De Beers, which began the engagement campaign as part of a 1938 advertising blitz aimed at pulling the diamond market out of its Depression-era slump. Over the next 40 years, De Beers’s advertising budget grew from $200,000 to $10 million per year as the industry realized the words they used to describe diamonds were as valuable as the stones they pulled from the ground. Diamonds were not just Forever, they were also a Girl’s Best Friend, de rigueur for engagements, encouraged for anniversaries, a Valentine’s Day staple. De Beers had stage-produced a massive increase in consumer demand to fuel a diamond market it already mostly controlled.

But there was a shocking secret behind De Beers’s romance machine: Diamonds weren’t actually valuable. De Beers stockpiled huge surpluses of the stone, artificially maintaining high prices. “Diamonds are intrinsically worthless,” Nicky Oppenheimer, then-chairman of De Beers, admitted in 1999, “except for the deep psychological need they fill.”

Billions were spent creating that need, and even though man-made diamonds only account for up to 2 percent of jewelry sales, the industry shudders at the idea of competing with gems produced at the push of a button. Fears of infiltration aren’t unfounded, either. In 2012, a lab in Antwerp discovered 600 man-made diamonds salted into a parcel of mined diamonds.

An advertisement for De Beers in 1960. (Photo: SenseiAlan/CC BY 2.0)

This is why you won’t hear traditional diamond traders referring to the Foundry’s product as a miracle; they employ a word that makes you think of plastic-wrapped cheese—“synthetic”—though they grudgingly accept “lab-grown,” “man-made,” or one of the other terms suggested by the Federal Trade Commission to ensure consumers know what they’re buying.

After the synthetics-mixing scandal, the world’s largest diamond exchange made its anti-man-made stance clear by adopting the slogan “Natural Is Real.” In fact, nowhere will you find a group of people so passionately engaged in the definition of words like “real” and “natural” and “authentic” as in the diamond industry. Take Brad Congress—the “romance specialist of southwest Florida”—a third-generation, 44-year-old jewelry dealer.

He regularly pores over trade publications for ads employing “deceptive” language, sending findings to the industry’s compliance arm, the Jewelers Vigilance Committee, whose staff has been known to hit shops incognito to ensure dealers aren’t overreaching, word-wise.

Congress even invented and secured the URL for his own word, diamonditis, a term he defines, basically, as owning a diamond that isn’t what you think it is. “Oftentimes I have to burst the bubble with someone. They thought they had something natural, and then [I] tell them, ‘I am so sorry—it is synthetic.’ That’s why I’m so ethically charged on the subject,” Congress says. “It hurts.”

Tools of the trade at Diamond Foundry. (Photo: Courtesy Diamond Foundry)

Neither he nor any estate dealer he knows will sell synthetic diamond jewelry. For Congress, the issue is financial. While some man-made diamonds retail for 10-30 percent less than natural stones, their cash-in value tends to be far lower. He also cites simple economics: As technology improves and it gets cheaper to manufacture more man-made diamonds, their value is bound to fall.

After all, a diamond may be forever, but the romance it commemorates often is not. Consequently, the resale market—which the mining industry can’t control—remains overstocked. Diamonds are a terrible investment. Retail markups range from 100-200 percent, which means a typical diamond ring or bracelet loses at least 50 percent of its value as the jeweler’s door shuts behind you.

And when it comes to putting a price on factory-made diamonds, manufactured scarcity isn’t exactly new. As De Beers once proved, value can be conjured from something as slight as a metaphor. Is it so impossible to imagine a techno-diamond also fetching a premium?

A diamond engagement ring. (Photo: littlesam/shutterstock.com)

It’s tempting to assume that someone committed to mined diamonds sees the industry’s ecological and human rights problems as a necessary evil. Not Congress. He considers himself an environmentalist. He drives an electric car. Last year, he and his wife launched a jewelry line made from recycled gold. He’s sympathetic to consumers wanting ethical, conflict-free stones, and steers them toward antique jewelry from an era predating industrialized mining. In fact, some of the industry’s biggest players maintain a fierce commitment to mined stones while actively fighting the environmental and human rights abuses around them.

Two weeks before my visit to Diamond Foundry, in the eighth-floor conference room of a heavily fortified skyscraper at the edge of New York’s diamond district, I sat facing one of these players: Martin Rapaport, a fire hydrant of a man who worked his way up from a job as a lowly diamond butcher, sorting and cleaving rough stone in Antwerp, to become one of the most important men in the industry.

Rapaport created the first global diamond pricing index (the “Rap Sheet”) and heads a leading diamond trading network (RapNet). His influence within the clannish world of diamond dealers is regal and omniscient. But that day, he was yelling like the sidewalk barkers selling fried nuts on the street below.

“Leonardo DiCaprio is a rabbi taking ham sandwiches and telling everybody, ‘They’re kosher!’ He is saying that a synthetic diamond, which takes food out of the mouths of people who are starving to death, is a better product to wear than something that could actually help these people by having a fair-trade diamond!”

The options for sourcing ethical diamonds: conflict free or synthetic? (Photo: Alice Nerr/shutterstock.com)

Though Rapaport’s career is built on diamonds mined from some of the poorest reaches of the globe, he’s no apologist for the industry. Nearly seven years before Blood Diamond turned the human grist of Sierra Leone’s mines into headlines, he toured the country’s amputee camps.

“Thousands of people. An arm. A leg. An arm and a leg. Little children,” Rapaport recalled. “You have to understand—my parents, they were in Auschwitz. I saw this and said, ‘What the hell is this? This cannot happen.’”

Despite the legacy of violence plaguing Africa’s diamond mines, Rapaport believes in a solution: fair-trade diamonds, the proverbial $4 latte that lifts thousands of subsistence-level diggers out of poverty. But more than a decade of effort by concerned stakeholders has failed to produce a foolproof fair-trade diamond certification scheme. Even the Kimberley Process—the UN-supported initiative to keep conflict diamonds off the market—is compromised. Some members of the coalition boycotted this year’s plenary meeting because it took place in the United Arab Emirates—“the go-to place for illicit gold and diamonds,” according to the dissenters—in protest over the country’s dodgy import controls, which commonly allow conflict diamonds onto the market.

Given the bleak prospects for truly feel-good diamonds coming out of Africa’s mines, man-made diamonds could be an alluring alternative. But Rapaport views diamond manufacturers as remorseless technocrats, freeloading off of mined diamonds’ value while doing nothing for impoverished miners. In countries like Botswana, he says, 40 percent of government revenue is derived from the diamond industry. The solution, he insists, isn’t to stop mining (or, in his parlance, “‘Hey, you million and a half diggers and the seven million people you’re supporting, all of you go to hell—we’re going to sell synthetic diamonds!’”) but to convince people to buy diamonds that actually help people.

When I present this argument to Martin Roscheisen, who’s never visited a mine, he shrugs it off as twisted logic. “That also would justify releasing the Mexican drug leaders from jail,” he says, smiling. “After all, they employ a lot of people.”

Besides, he insists, Diamond Foundry’s clients “are people who would not buy a mined diamond.” The company’s first production run sold out within two weeks, at prices exceeding those of natural diamonds.

“The only diamond they would want to have is a diamond like ours,” Roscheisen says, rising at the sound of the door buzzer. And with that, he excuses himself. The FedEx guy has just arrived with a gift for his girlfriend: a custom diamond, born in California.

![]() This story was co-produced with mental_floss magazine and appeared in the June/July 2016 issue. Click here to subscribe.

This story was co-produced with mental_floss magazine and appeared in the June/July 2016 issue. Click here to subscribe.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook