The Insolent Chauffeurs of America’s Early Automobile Era

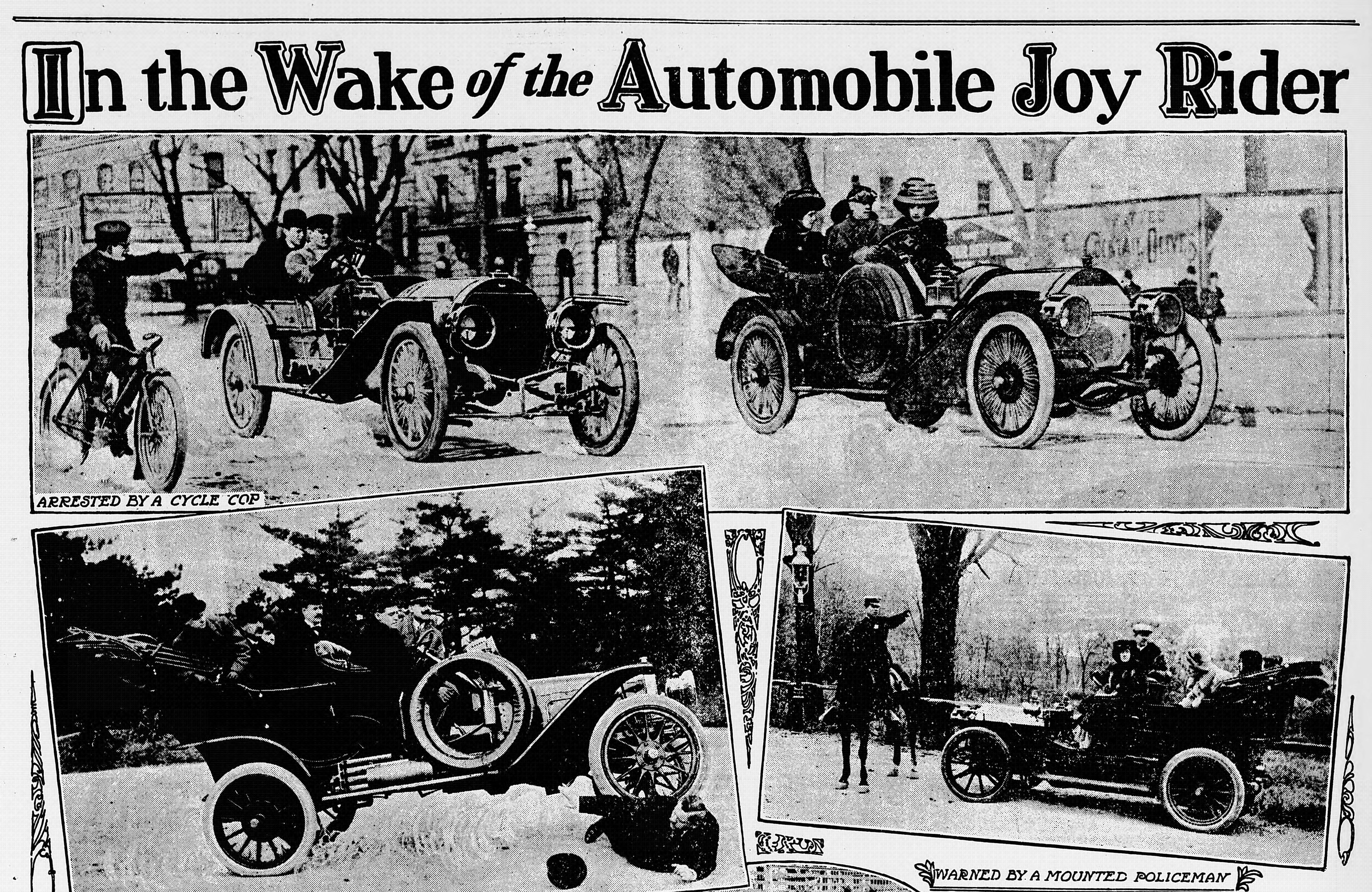

The media criticized drivers for off-the-clock joyrides, corruption, and running people over.

Early in the morning on September 21, 1909, a Brooklyn chauffeur driving at high speed, a rogue policeman who was participating in the joyride, and 10 people riding in a farm wagon were seriously injured after the chauffeur, John McAnderies, crashed into the wagon. The “joy-riding” of Mr McAnderies was blamed for this collision.

This crash was no isolated case. In the beginning of the 20th century, the United States seemed to be full of reckless drivers causing chaos and damage in vehicles that belonged to their employers. As the Washington Times of October 11, 1908 claimed, while European chauffeurs occupied a position of standard servitude, “groveling without a thought of rebellion,” this was not the case in the United States, where the American chauffeur “lords it over the auto, the roadway and the general population.”

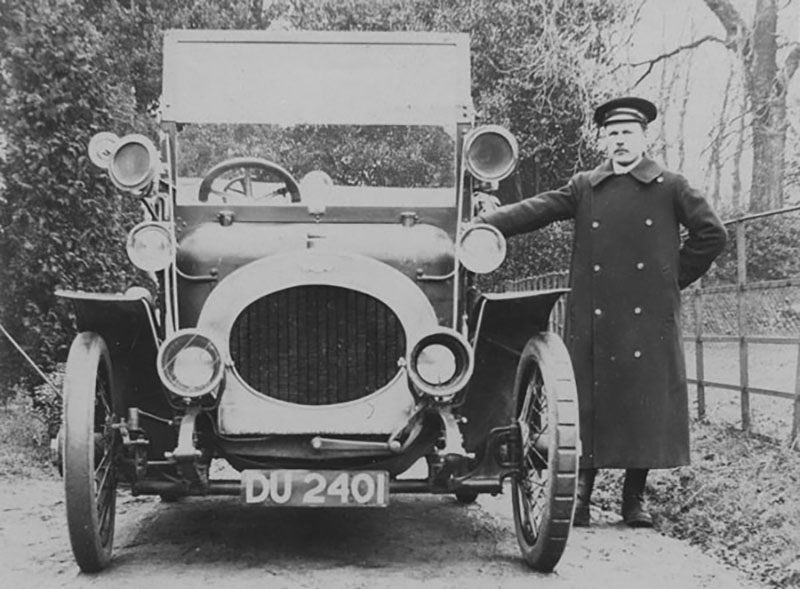

In the early 1900s, automobiles, a relatively new invention, were a “plaything for the rich,” says Dr John Heitmann, a Professor of History at the University of Dayton. Those who were wealthy and privileged enough to own cars were often unsure of how to operate them. So for both practical and status reasons, a chauffeur was hired. The number of chauffeurs increased rapidly, so much so that around 1908 the majority of car-owners in the state of New York had a chauffeur.

By 1911 there were 450,000 cars in the United States and 100,000 chauffeurs. These drivers seemed to have unprecedented power and control over their employers. Dr. Kevin Borg, a history professor at James Madison University, says that between 1903 and 1912, this situation was often termed the “chauffeur problem” by the chauffeur’s employers and automobile garages’ managers.

Instances of joyriding chauffeurs began appearing in the press throughout the United States. One report from 1906 recounted how a “reckless chauffeur” had zoomed past a horse carriage, which frightened the horses into running away and caused the carriage to overturn, injuring the occupants. However, the joyrider could not be apprehended as neither their identity nor their number plate was known.

Apprehending a joyriding chauffeur who was drink-driving and even running people over was not always a straightforward process. Even if the automobile had a registration number that could be spotted, it might not be correct. One North Dakota newspaper article from 1909, which detailed all of the mischievous antics chauffeurs used, noted that “to evade detection he often hangs a false number on the machine” and “if he runs over anybody which he frequently does, it is his favorite trick to put on extra speed and escape before he can be arrested.” The same article suggested that chauffeurs were inclined to gather up “women of questionable character and drinks that are still more questionable” and then go on to “ride up the town.”

Joyriding was only one part of the chauffeur problem. In the early 20th century, many automobiles were stored publicly in garages. The chauffeur often had significant power over where the cars were housed and who had access to them. This meant that the chauffeur in question could gain influence on the garage owner and often obtain 10 percent of whatever the fees were for the storage of the automobile. If owners were unwilling to pay, chauffeurs had ways of extorting the money. This could include deliberate damage to the vehicle by the chauffeurs who then placed the blame on the garage owner, leading to their employer no longer wishing to do business with the garage.

Another way that chauffeurs could abuse their position involved passing off the employer’s car as their own and making money ferrying other passengers. This illicit service was aided by the garage owners who were hesitant to question the chauffeurs about their unauthorized use of the automobiles. Drivers could profit handsomely by hiring themselves out as a “limousine service to downtown theatergoers.” Sometimes it was only after the automobile crashed that the owner would become aware the car had been even taken from the garage.

Other infractions, as reported by the New York Tribune in November 1910, included chauffeurs blaring noisy horns without thought for those around. Some of the horns were “locomotive whistles,” blasted at a volume “enough to wake the dead.” Rather bizarrely, chauffeurs were also singled out in the report for their “desertion of wives.” Dr John Heitmann also notes that there were wider concerns about the relationship between a chauffeur and the wife of the car owner.

Those who felt victimised by the chauffeurs were occasionally stirred into action. In 1905, at a meeting of the Automobile Club of America in New York City, a Mr Shattuck noted that for chauffeurs the “temptation to fraud had been very great.” One newspaper article from the Yorkville Inquirer of January 20, 1911 considered whether a trained marksman could hit a joyriding chauffeur as a last result if they were unable to obtain to take down their license number required for an arrest. The newspaper admitted that, most likely, passersby would get hit.

Less drastic and more amusing solutions for dealing with chauffeurs’ reckless joyriding were also proposed. A cartoon in the Omaha Bee of September 7, 1909 suggested an automobile design with the chauffeur’s section placed comically far ahead so that any collisions would endanger the driver rather than the passenger. This, it was argued, would “discourage reckless driving.”

Fines were also suggested as a way of dealing with joyriding chauffeurs. Increased legislation meant that the chauffeur could be held financially responsible for any damage they caused, while the owners of the car would not be accountable so long as they would act as a witness against the chauffeur. The Evening World of June 6, 1904 illustrated all the ways whereby a “reckless chauffeur” might have to pay heavily. Institutionally, establishments were created by motoring clubs to provide owners with repairing and tyre services for their cars in order to navigate around financial exploitation by chauffeurs.

But the “chauffeur problem” did somewhat persist. In 1909, one hearing over the Allds-Hamn Bill, which sought to punish “ joy-riders” in New York, declared that 90 percent of automobile accidents were caused by “joy-riding chauffeurs.” Drivers defended themselves in publications like The American Chauffeur: An Automobile Digest. “Professional chauffeurs are hardly ever to be found intoxicated,” read one article, published in 1914, “this being a habit indulged in largely by the so-called joy rider type.” Some chauffeurs also blamed pedestrians, stating that if it were not for the “jay walking” of irresponsible pedestrians, joyriding would be harmless.

By around 1914, the power of the chauffeur had been weakened through legislation that restricted their freedom and increased surveillance in motor garages. Although chauffeurs made attempts to organize, they could not reclaim the position they had once held. Drivers-for-hire became more regulated and under the control of their employers and the motor garages.

Chauffeurs’ authority was further undermined by their employers’ reduced dependency on them. “Motorists could turn elsewhere for mechanical expertise, rather than to chauffeurs,” says Borg. With more and more cars every year, “automobile and mechanical knowledge diffused,” particularly “with the motorization of the U.S. Army for WWI.” The technological foundation on which the chauffeur’s power rested had been removed, and growing numbers of motorists who could not afford chauffeur got behind the wheel themselves. Joyriding was over. The insolent drivers had been tamed. And with that, the chauffeur problem was solved.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook