At the Church of 8 Wheels, Roller-Skating Fans’ Prayers Have Been Answered

This former house of worship in San Francisco is now a hotspot for skaters of all ages.

At 4:45 p.m. on a Friday afternoon in early January 2019, a dozen kids, aged 10 to 17, congregate on the sidewalk outside a large church on the corner on San Francisco’s Fillmore and Fell Streets. As the minutes pass, more kids, some of them accompanied by their parents, stroll up and join the group. They laugh together and bounce on their heels in anticipation, taking frequent glances up the stairs, waiting for the front doors to push open and welcome them inside.

Finally, at 5 p.m. sharp, three bells sound from the tower, the doors open, and an African-American man, wearing a glittery, gold-and-white top-hat; a long, fur-lined robe; and fuzzy roller skates—like a superfly Willy Wonka—stands at the top of the landing, smiles, and invites everyone to come in, pick up their skates, and have fun.

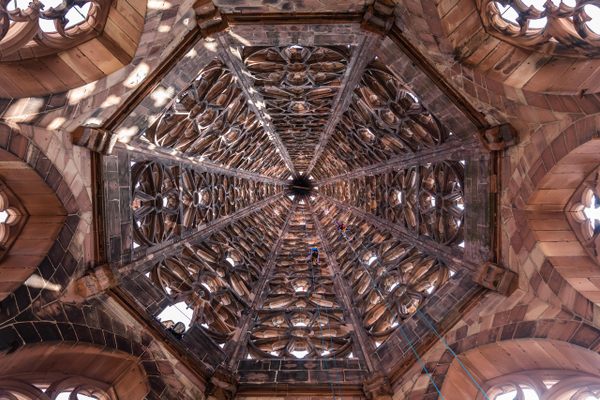

This isn’t a sight you’d expect to find at most churches, but the Church of 8 Wheels isn’t your ordinary church. It isn’t, technically, even a church—at least not one with any particular tenet or dogma, other than the gospel of roller skating. In front of a neon-lit altar, a DJ plays disco, soul, and pop music, while skaters make their revolutions underneath disco balls, laser lights, ceiling frescos, and stained-glass windows of Jesus and the Virgin Mary.

At the center of it all is founder, impresario, emcee, and avowed “Godfather of Skate,” David G. Miles, Jr. For four decades, Miles has been an evangelist for roller skating in the Bay Area: promoting skating in schools, advocating for car-free spaces, and organizing charity skates (he has led skaters from San Francisco to Los Angeles 15 times for charitable causes). He’s also a fixture at Burning Man, where, for 19 years, he’s managed Black Rock Roller Disco, a full-size roller rink in the middle of the desert.

For Miles, roller skating isn’t a hobby, an idle curiosity, or something exclusive to children’s birthday parties. It’s a lifestyle, one with numerous social benefits.

“I want to make people look at skating as not just this fad that goes in and out,” Miles says. “I want people to take it seriously. It has serious implications, for transportation, health, and community.”

Miles arrived in the city 40 years ago, in February 1979, “on a one-way bus ticket from Kansas City.” He was 22 years old. He quickly fell in with the local roller-skating community, becoming head of the Golden Gate Park Skate Patrol—a volunteer unit that enforced park rules and maintained safety—and the de facto leader of the Golden Gate Park Sunday sessions. Every Sunday for the past four decades, large crowds of roller skaters have descended on Golden Gate Park, skating and partying together underneath the open sky, with Miles’s mobile DJ unit providing music.

But only five years ago Miles realized he wanted a place for people to skate during the rainy months. Roller rinks had been shuttering all across the country, and the Bay Area was not immune. The few surviving roller rinks were outside San Francisco’s prohibitively expensive real estate markets, in places such as San Ramon and Antioch, a 45- and 50-minute drive away, respectively.

A friend told Miles he knew of a church in the Fillmore District that had been sitting empty since 2004, now owned by a property management company. Miles made some inquiries and, after cleaning up the space and making some renovations, he began hosting weekly roller disco parties inside the nearly century-old Sacred Heart Catholic Church.

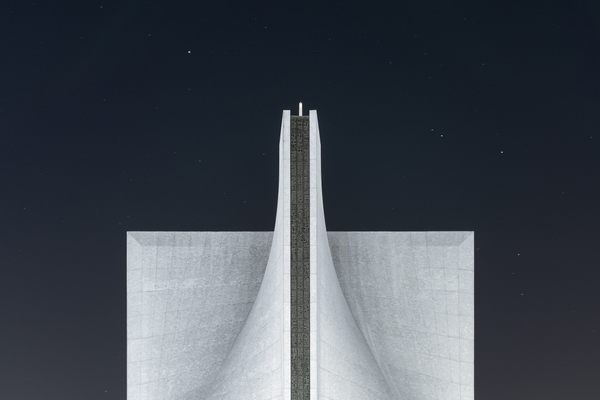

Completed in 1898 by the renowned San Francisco architect Thomas John Welsh, Sacred Heart is a broad and imposing Romanesque building, with Tuscan columns and a lofty bell tower, looking out over the Western Addition and Hayes Valley. Over the decades, the church served the changing demographics of the neighborhood, starting at the turn of the 20th century with a congregation made up largely of Irish immigrants. In the 1930s and ‘40s, as tens of thousands of African Americans came to the city for work, largely concentrating in and around the Fillmore District, Sacred Heart soon had the distinction of being one of San Francisco’s only predominantly African-American Catholic parishes.

In the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, the parish became a center of social activism, under the brief, radical, and often controversial leadership of Father Eugene Boyle. An outspoken advocate of civil rights, fair housing, and the farm labor movement, Father Boyle opened Sacred Heart’s doors to Vietnam War protesters, labor activists, and the Black Panther Party, who held their free breakfast program for children in the parish’s basement.

But though the building had survived the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and the Loma Prieta quake in 1989, the church was issued a $8,000,000 seismic repair bill in 2004 that it now found itself unable to pay. Church and community members joined with landmark preservationists to raise $280,000 in a campaign to save the church, but with a declining number of parishioners, rising costs, and deteriorating infrastructure (a net had at one point hung over the pews to catch falling plaster from the ceiling), Sacred Heart held its final Mass on December 26, 2004.

The building soon fell into neglect and disrepair. According to Miles, people broke into the building to use drugs in the basement. Many of the adornments, including the marble altar and some of the stained-glass windows, were removed and sold by a building owner. After changing ownership at least twice, the building was purchased by a San Francisco-based contractor, who’d intended to replace the church with residential units.

That’s when Miles stepped in. But he saw immediately that he had his work cut out for him. “This place was a wreck, man,” he says.

Agreeing to a week-by-week trial run with the owner, Miles swept out the trash, ran out the drug users, pushed the church pews against the walls, and replaced the 3,800-square-foot tile floor with a polyurethane-coated wooden rink. He installed a disco ball, strobe lights, and a state-of-the-art sound system. After the success of the first couple of months, Miles signed an extended lease with the property owner in 2013, establishing a legitimate home for the newly christened Church of 8 Wheels.

Every Friday at five p.m., the church opens for two hours to skaters of all ages, bringing kids and teens just out of school for the weekend. Two hours later, the doors close, then reopen at eight p.m. to skaters 21 and older, staying open until midnight. Saturday afternoons are available for instructors (or “apostles”) to give skating lessons; three to five p.m. is reserved for families; and the weekend ends with another adult skate session, from seven to 11 p.m. It costs 10 dollars to enter, and an additional five dollars to rent skates. The church is also available to rent for private events, or corporations looking for an unconventional party experience.

The only official employee is the operations manager Daniel Albert, who is himself a longtime skater. Teens volunteer at the rental booth in exchange for skating time, and Miles’s wife, Rose, collects money at the door. Rose and David met in May 1979, while the two were skating at Golden Gate Park. They have two daughters, one son, and one granddaughter, all of whom have taken up roller skating. Their son, David Miles III, is also the house DJ, and can be seen Fridays and Saturdays at the neon-lit DJ booth, playing crowd-favorites such as Michael Jackson and Prince.

The popularity of the Church of 8 Wheels owes in large part to its novelty. But that novelty is also somewhat tinged with nostalgia for a bygone era. San Francisco, of course, is not the same city it once was. In the 1970s, San Francisco was synonymous with eccentricity, flamboyance, and free-spiritedness. But in the past two decades, as the tech industry has established its seemingly indomitable presence, contributing to skyrocketing living costs, many of the artists and other bohemians have been priced out of the city. Hayes Valley, home of Sacred Heart Church, was once a working-class and predominantly African-American neighborhood. Today it is known more for its chic fashion shops, upscale restaurants, and trendy boutiques. In 21st-century San Francisco, there are fewer and fewer places in the city to let your freak flag fly. That’s perhaps the biggest appeal of the Church of 8 Wheels. It not only provides a space to dress up, act weird, and be part of a community; it represents a time when these things were part of daily life.

While the church fills a unique niche in the city, it is also unique among other roller rinks, due to the diversity of the skaters and the historic legacy of the building. And unlike conventional roller rinks, elaborate costumes are not just welcomed at the Church of 8 Wheels, but encouraged. “Roller rinks have rules: ‘You can’t do this, you can’t do that,’” Miles says. “I don’t have that. My rule is, you can’t let what you do hurt others. And you need to let people be themselves. If you can do that, you can hang.”

The church has been visited by tourists, CEOs, and local politicians, and it received national attention in August 2015, when Caitlyn Jenner laced up a pair of skates for an episode of her show, I Am Cait. But for the most part the clientele consists of locals of all ages, ethnicities, and skill levels.

During my first visit, to a Friday afternoon all-ages session, Miles was out on the rink, patiently helping kids who were struggling to stay upright. “Put your feet in a V and walk like a duck,” he tells them.

I returned the next night for the adult skate, and the vibe was more carnivalesque—and much more crowded. A line stretched out the door the entire night. Capacity is currently 149 (Miles says he is making renovations to accommodate 100 more), and it felt like we were pushing right up against that threshold. Skaters were shoulder to shoulder. There were at least two birthday parties. Many people had come dressed in glitter, wigs, and technicolor tights. It felt like being in the hottest nightclub in town, albeit one where people regularly fall on their butts.

Though managing the Church of 8 Wheels now occupies much of his time, Miles feels as passionately about skating as he did the day he stepped off the bus in 1979 and laced up his first pair of skates.

“There’s a sense of freedom about it. It’s a very unique thing,” he says. “I just get a kick out of it. I love skating. It’s free, it’s fun, it’s inclusive. It’s a rainbow of people, from all walks of life. There’s nothing to prove. If you’re a great skater, that’s cool. But if you’re not, that’s cool too.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook