Preserve Your Quarantine Nature Walks With a DIY Herbarium

Pressed plants can be your journal of the pandemic.

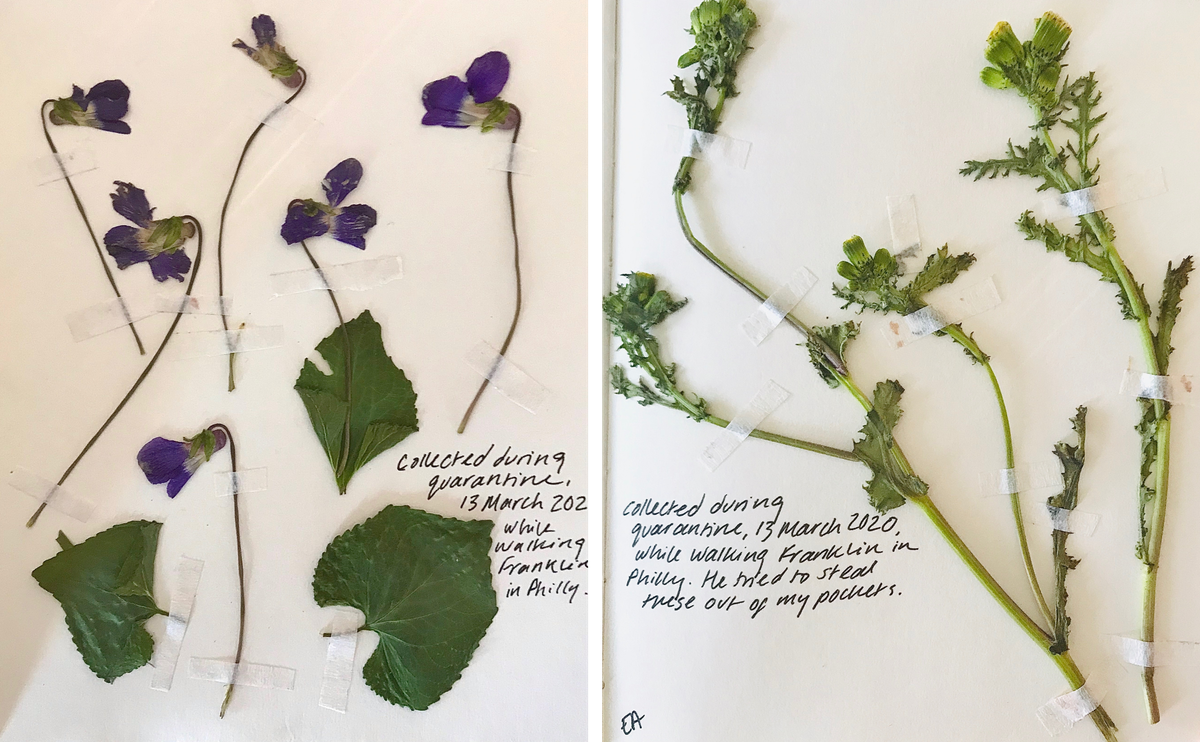

Even in the era of COVID-19, Elaine Ayers is usually at the park by 7:00 a.m. When her goldendoodle, Franklin, has gotta go, he’s gotta go—“He’s still a baby even though he’s like a hundred pounds,” she says—and they head out for short walks several times a day in the Philadelphia neighborhood of Fishtown. She doesn’t see many people at the moment, but as they head home, she marvels at their leafy neighbors. Ayers, who teaches in the museum studies department at New York University, studies 18th- and 19th-century botanical specimens, but lately she has become especially attuned to their more contemporary counterparts—native plants thriving under an overpass, cherry blossoms painting the parks pink, weeds shoving up through the concrete. “When I go on these walks to take my dog out to pee, I’m really noticing what’s around me kind of for the first time and I’m appreciating it more than I ever have,” she says.

A few weeks ago, with the realization that social distancing isn’t going away any time soon, and that she likely won’t teach her current crop of students in person again, Ayers was feeling “lonely and disconnected and sad, and in need of a little beauty.” She poked around her house for a notebook to write in. Most of them were locked in her office in New York, nearly 100 miles away, but she found a few well-loved ones, around a decade old and stuffed with pressed plants. At the time, she had been in the habit of making pressed specimens to commemorate big life events, from going to graduate school to weathering a breakup. Upon rediscovering her old specimens, she wondered if, in the midst of a pandemic, collecting and pressing plants might be a soothing exercise and a useful record of how people are interacting with nature.

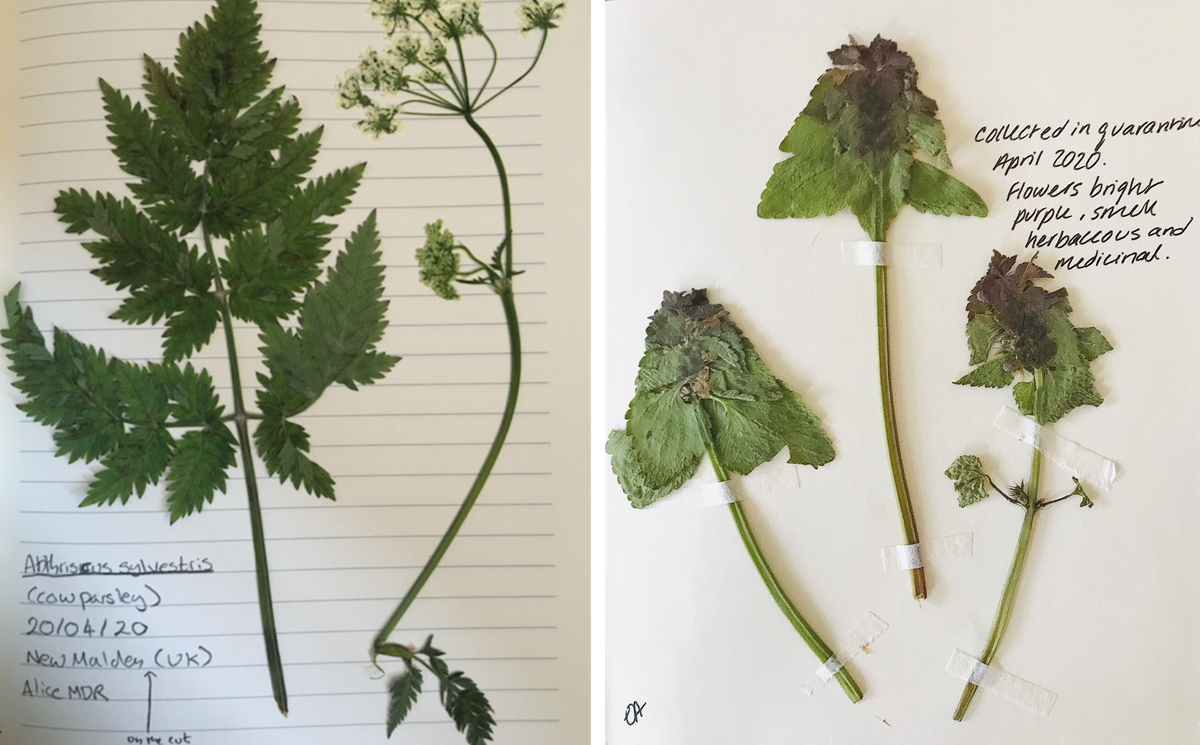

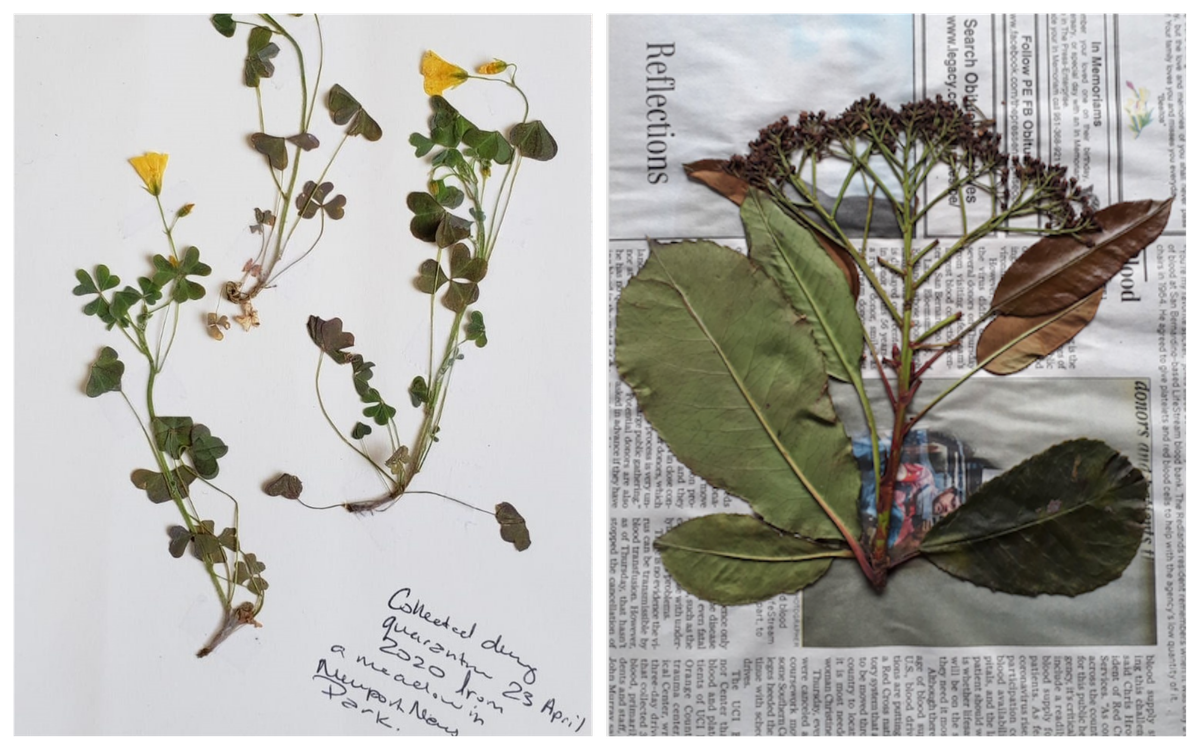

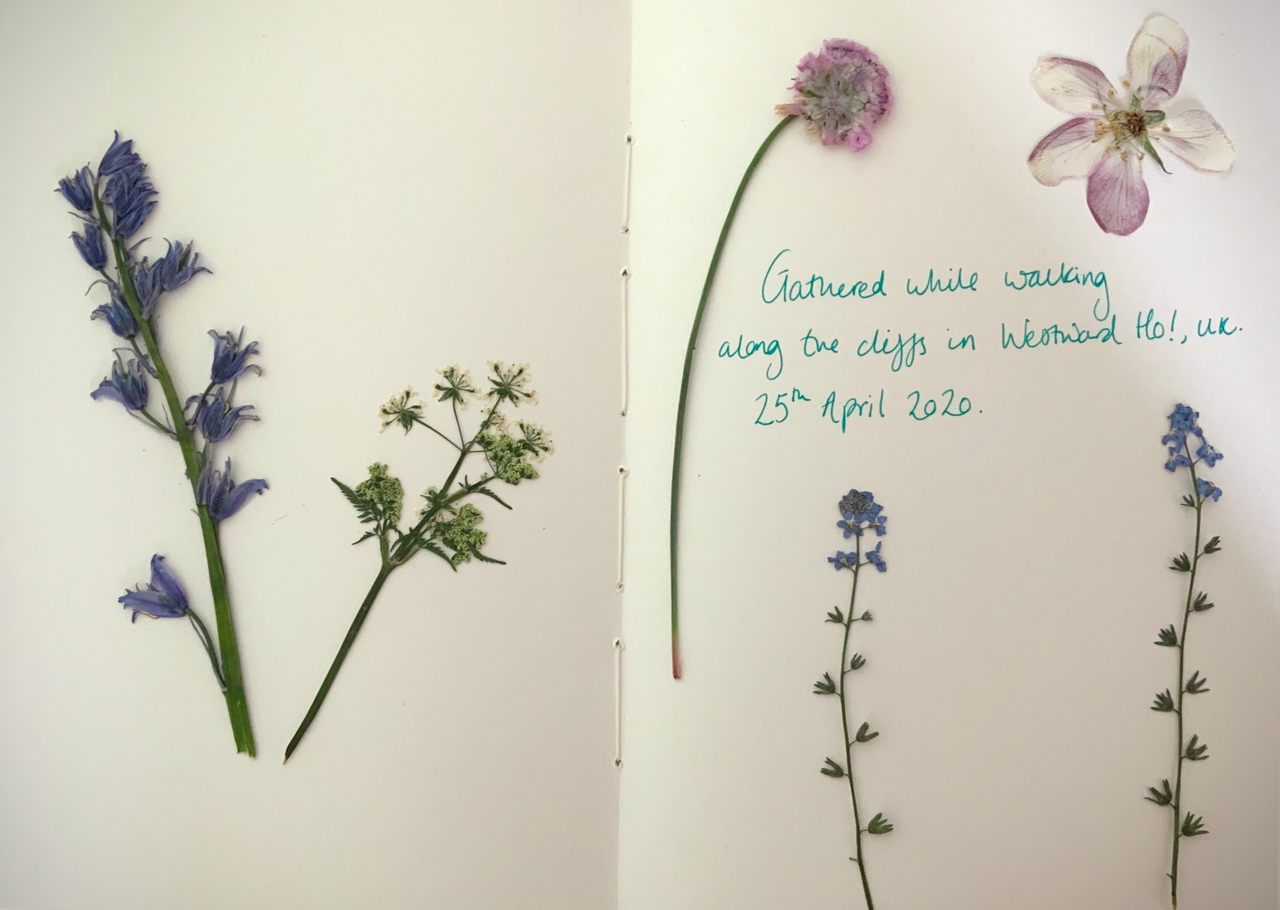

Inspired by the 19th-century habit of sending pressed plants through the mail, Ayers launched the Quarantine Herbarium as a digital scrapbook of weeds, flowers, herbs, or leaves that people find, press, and photograph. So far, 20 participants from Philadelphia, California, England, and elsewhere have shared 50 specimens, and Ayers is expecting images of 30 more plants in the coming week.

Historically, botanical specimens were often collected, pressed, and mounted by women and indigenous people, who “don’t show up in the scientific record even though they were trading all of these specimens through the mail and customs houses,” Ayers says. Part of her project involves poking at the concepts of expertise and authority. Participants don’t need to have deep botanical knowledge. Anyone can press a plant.

Making an herbarium requires little more than pressure and time. Sandwich flowers or leaves between sheets of newspaper, blotting paper, or some other absorbent material, and then bury them beneath a stack of hefty books. Wait a week or so, until they’re dry to the touch, and then use tape or acid-free glue, such as Elmer’s, to affix them to acid-free paper. Jot down the species and where you found it—the park, your yard, or maybe even the corner of your living room (houseplants are fair game).

“Some plants are just easier to press than others,” Ayers says. “Things that are already dry tend to work well.” Grasses, ferns, and tree leaves qualify. Oak leaves, for instance, are hardy and hold their shape without disintegrating the way a delicate flower might. Some blooms, once squashed, don’t look like much, especially when their color fades. Ayers’s recent experiment with pressed dandelions wasn’t a smash success. It “looks like a big, smushy, brown blob.” But that’s no reason not to try. “I don’t think the end goal here should be to make like the most beautiful identifiable pressing,” she says. “It should be to enjoy the process and have a true account of what you’re seeing. And if that ends up being a bunch of plants but don’t press well, I think that’s kind of fine.”

Herbaria are often snapshots of a moment in time, particularly when pressed specimens are still between old newspaper clippings. Researchers digitizing centuries-old examples can also get an idea of what lived where and how climate changes have affected plant populations. With enough entries and time, a quarantine herbarium could offer some similar insight, but in the meantime, a personal herbarium doubles as a calendar or a diary, a record of the way that millions of people’s lives have changed.

When interviewed for an Atlas Obscura story about how museums are preparing to collect ephemera that will help tell the story of COVID-19, Benjamin Filene, associate director for curatorial affairs at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, suggested that people consider keeping a quarantine journal of their routines and how they’re making sense of a scary moment. Such a habit “could be a therapeutic thing of marking time in a moment when the days start to blur,” he said, and jog our memories later. Though it seems like this moment will drag on forever, it won’t. Eventually our recollections of it will start to fog up. “It’s easy, when you’re living through something, to forget how much will feel unfamiliar to you a year or two from now,” Filene said, “not to mention 10.” Some of us may want something to tether us to the feeling of this time.

Herbaria are a way of journaling with the help of nature. The first submissions might include the daffodils and bluebells of early spring. As the calendar changes, so will the species, an incidental record of how the months keep crawling along. Someday, the pressed and preserved plants will be a reminder of isolated days, and the little joys we’re all seeking.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook