C.S. Lewis’s Greatest Fiction Was Convincing American Kids That They Would Like Turkish Delight

What would the perfect fantasy treat look like? Depending on where you’re from, probably not this.

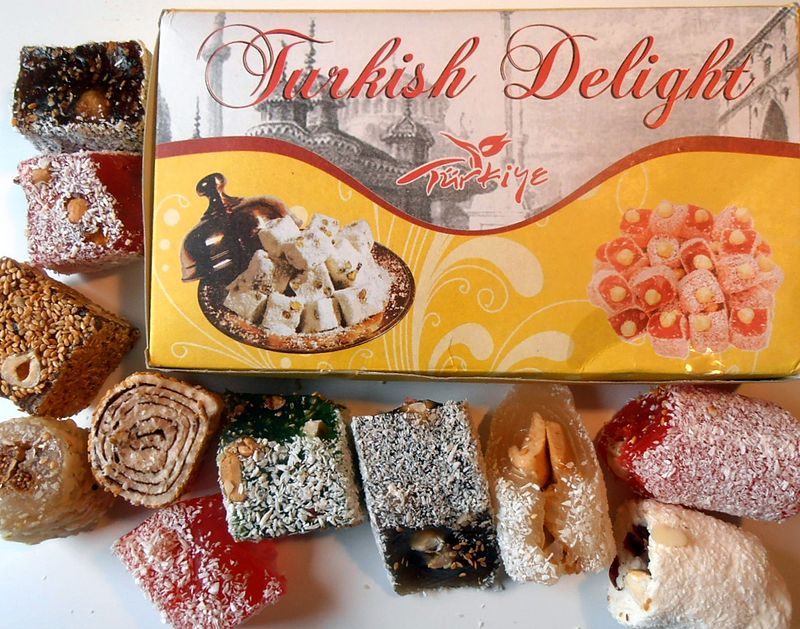

Turkish Delight, or lokum, is a popular dessert sweet throughout Europe, especially in Greece, the Balkans, and, of course, Turkey. But most Americans, if they have any association with the treat at all, know it only as the food for which Edmund Pevensie sells out his family in the classic children’s fantasy novel The Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe. Until I first tried real Turkish Delight in my 20s, I had always imagined it as a cross between crisp toffee and halvah—flaky and melting in the mouth. Here’s what it really is: a starch and sugar gel often containing fruit or nuts and flavored with rosewater, citrus, resin, or mint. The texture is gummy and sticky, some of the flavors are unfamiliar to American palates, and the whole thing is very, very sweet. (In addition to the sugar in the mixture, it’s often dusted with icing sugar to keep the pieces from sticking together.) While some Turkish Delight newbies may find they enjoy it, it’s not likely to be the first thing we imagine when we picture an irresistible candy treat.

I figured other people who had encountered Narnia before they encountered lokum probably had misconceptions just like mine, so I set out to discover what Americans imagined when they read about Turkish Delight. What kind of candy did we think would inspire a boy to betray his brothers and sisters?

The English name, Turkish Delight, is no misnomer. Turks make and consume lots of lokum, and it’s a popular gift, a sign of hospitality. The candy was invented in the early 19th century, reportedly by confectioner Bekir Effendi—though this claim comes from the company Hacı Bekir, still a premiere manufacturer of lokum, which was founded by Bekir and named after him. (He changed his name to Hacı Bekir after completing the hajj, or pilgrimage to Mecca.) According to the Hacı Bekir website, Sultan Mahmud II was so pleased by the new sweet that he named Bekir chief confectioner.

But outside of countries where Turkish Delight is a ubiquitous treat, many people first encounter it via The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe, the first installment of C.S. Lewis’s beloved Narnia books (or via the 1988 TV miniseries, or the 2005 movie). In the book, Edmund is tempted by Turkish Delight into an alliance with the White Witch, who has brought eternal winter to Narnia. When Edmund first meets the witch, she asks him, “What would you like best to eat?” He doesn’t even hesitate.

England’s wartime sugar rationing probably figured into that choice. The reason the Pevensie children were staying in an old house with a portal to Narnia in its wardrobe is that it was World War II, and kids were being relocated due to bombing risks. Candy, too, was a casualty of the war. During the war, and well into the postwar period, sugar was strictly rationed in England; in 1950, when Lewis published the first Narnia book, the allowance was half a pound of candy and chocolate per person per month. It’s no wonder that, when the White Queen asked him what he liked best, Edmund’s answer was a confection that is almost entirely sugar.

Most Americans, though, didn’t know about that when we first read the book. All we knew was that Turkish Delight was an exotic-sounding treat that would be your first request if a mysterious and elegant woman asked you, “What would you like best to eat?” And we knew that Edmund loved that Turkish Delight so much that he put his siblings and the entire land of Narnia in harm’s way in exchange for more. (To be fair, it was enchanted. But still, Edmund. Still.) So we wound up imagining whatever we would have liked best. It was like looking into Harry Potter’s Mirror of Erised, but for desserts: When you think of a treat worth betraying your family for, what do you see? Turkish Delight is our collective candy id.

I asked my friends and acquaintances what they imagined when they first read about Turkish Delight. Their answers spanned a whole range of sweet treats—and some surprises.

My friends who grew up in England empathized with Edmund. Adrian Bott was born long after sugar rationing, but still got positively poetic in recalling the treat: “Rose-hued irregular cubes dusted silvery with icing sugar, arrayed on a doily in gentle disarray like a toppled Stonehenge. Edmund’s temptation was entirely understandable and one rather felt that in his place, one could hardly have done other than he did.” (Bott is a children’s author, if you couldn’t tell.)

For kids who weren’t already familiar with it, though, “Turkish Delight” was likely to be meaningless—which meant we could project onto it whatever confection seemed most delicious. “I imagined it was better and more sophisticated than anything I had ever tasted, considering that Edmund was willing to sacrifice his entire family for just one more piece,” said Coco Langford, who described her childhood vision of Turkish Delight as “rich, but still delicate, chewy and soft, probably like some kind of vanilla or caramel fudge, with just enough nuts to add the perfect crunch.”

I feel like to me it was a thing made from marshmallows, just layers and layers of marshmallows kind of smushed together, like a marshmallow cake, with maybe the ones on top roasted like on a campfire (brûléed, I guess, although I would not have known that concept). I guess my kid brain just disregarded the whole “Turkish” element, and went with: What would a dessert literally called “delight” be like? It would be layers of marshmallows.

—Evan Ratliff

Kelly Taylor assumed that Turkish Delight was similar to her favorite sweet: “I remember at age 8 thinking that it would be like something nutty and chocolatey—my favorite candy bar at that age was a ‘Watchamacallit,’ sort of a crunchy peanut-buttery chocolate bar thing.” Having found the actual Turkish Delight “boring, bordering on gross,” Taylor says she still imagines the Narnia version as “fluffy crunchy nutty chocolatey goodness.” Clarice Meadows thought it was chocolate, too: “Not just any old chocolates but serious dark chocolate truffle chocolates that give you an extreme rush of endorphins.”

Not everyone thought the Ultimate Candy would be chocolate, though. Stefanie Gray pictured “a way fancier and differently textured old-school version of the pink Starburst” (the best Starburst, as everyone knows). Jaya Saxena also thought it was pink, “maybe some sort of frothy pink beverage that tasted just crazy.” And Claire McGuire only cared that it was very, very sweet: “I was so sugar-deprived as a kid that my idea of the ideal sweet, one you’d betray your family for, was basically pure sugar with some pleasing texture. Maybe like nougat, only softer.”

I definitely had no idea what Turkish Delight was. I gathered that it was a candy, so what I pictured was basically a lollipop like thing that was really tall and spindly. I had this vague sense that Turkish architecture involved buildings with big spindly towers. So I imagined these were like the long rainbow lollipops but not rainbow colored?

—Rose Eveleth

Some bright youngsters knew enough about Turkey to incorporate elements of its architecture or food into their vision of Turkish Delight. “I first thought it was baklava, because I had the vague idea that baklava was both Turkish and delightful,” said Michelle Rothrock. “I was correct about baklava, but not about Turkish Delight.” Dara Lind also thought it was baklava, “and then, upon being told it was not, assumed it was just the nougat part of a Snickers bar.” She found out the truth after visiting Turkey, or rather, after a layover in the Istanbul airport during which she gorged on Turkish Delight (“a TERRIBLE IDEA.”)

Jennifer Peepas’s version was influenced by baklava-type pastries too: “I thought it would be something crispy and fluffy, like those things my Yia-Yia made out of fried dough coated in honey. Like flaky baklava/crisp dough, but maybe with ice cream between the layers? When I finally tried it, the one I tried was flavored with anise/licorice, and I darn near puked.”

Barb Benesch-Granberg also took inspiration from Middle Eastern food, specifically its profusion of spices: “My mental picture involved something white and very fluffy and sort of ephemeral. And also involving exotic spices somehow. Like really dense cotton candy flavored with cinnamon, ginger, cardamom, and honey.” Colleen Robinson-Sentance, too, pictured something easily dissolved: “They were a rosy golden color in my mind, and almost instantly evaporated in one’s mouth, hence the obsessive desire they provoked.”

I expected it to be like Divinity, this white candy that all Southern grandmothers make at Christmas which is basically pecans suspended in clouds of sugar. It looks gorgeous, but it kind of tastes like nonsense. The first time I had it was when I was 18, and there was this MASSIVE Cadbury vending machine in either Gatwick or Stanstead. And one of the selections was a Cadbury Bar with Turkish Delight filling in it, and I was so excited to try it because it seemed so English and so Magical.

—Emily Dagger

A few subtler readers, though, imagined confections they didn’t actually like all that much. After all, the Turkish Delight in the book is enchanted to make Edmund crave it obsessively; yes, it’s the first thing he asks for, but when he subsequently gorges himself it’s partly the magic to blame. Besides, it’s Edmund. What does he know?

Kevin Doherty assumed Turkish Delight was like marzipan, even though he hated marzipan. “I guess Narnia seemed foreign and remote and the sort of place that would have that kind of sweet?” he said. “I also may have been subconsciously judging Edmund, like ‘What a tool, I bet he likes marzipan too.’” (This is a good guess. Given the sugar rationing, Edmund probably would have punched a faun for marzipan.)

So I was trying to remember my first impression of it, closed my eyes, and pulled up a mental picture of Edmund in the sled, stuffing himself full of … roast turkey. Apparently the first time I read it, I went by the words so fast that I didn’t even internalize the fact that “Turkish” does not equal “turkey.” And so this must have been really exceptional turkey. What the hell. And then in future rereads, my mental picture was already set, so it didn’t change for a long time. Of course, eventually I did realize that it was some sort of sweet, but I honestly am not sure what I pictured. I think that somehow it still looked like turkey.

—Joanna Kellogg

Here’s the thing about The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardobe, though: The book doesn’t actually say that Turkish Delight is a candy. It would have been well-known enough in 1950s England to render such an explanation unnecessary and a little silly, like describing a lion as “a type of big cat.” It’s described as light and sweet, and it makes Edmund’s hands sticky, but for a few people I talked to, that wasn’t enough to keep them from imagining it as some kind of savory snack.

Ann Tabor thought Turkish Delight was “meat … with gravy.” Sara Williamson agreed: “I think I also might have had some kind of Turkish/turkey confusion, because I thought it was like Thanksgiving stuffing that always stayed warm, and had the perfect ratio of soft and crispy parts.” Her conception was based partly on Narnia’s eternal winter—who would want jellied sweets on a cold day? Stuffing sounds way more comforting.

I honestly can’t even remember it anymore, I was so angry and upset when I found out what Turkish Delight actually was that whenever I try to visualize it all I can see is disappointment.

—Mallory Ortberg

There’s one thing almost everyone agreed on: Edmund’s willingness to put himself in the thrall of an evil witch in exchange for Turkish Delight makes him not only morally but gastronomically suspect. Though some Americans said Turkish Delight was okay, and a few had discovered they really liked it, the majority found that the aromatic sweet was definitely not their preferred dessert. The classic flavors, like rosewater and pistachio, aren’t familiar to American palates, and the texture—chewy, sticky gelatin—is polarizing. (Abroad, recipes often substitute gelatin, but true, traditional Turkish Delight uses corn starch.)*

The friends I talked to variously described Turkish Delight as “almost-solid perfume,” “like a blobby pink jelly baby,” “tastes like how cheap floral-scented cleaning products smell,” “gummy soap,” “flower-flavored atrociousness,” and “sticky gunky horror.” As for Edmund himself, responses included: “How sad was that kid’s life that the best treat he could think of was THAT?” “The boy had very poor taste.” “No child is that rapturous about something that is gelatin with nuts in it.” “It made me amazed they ever took him back.”

Maybe it’s the surfeit of sugar surrounding Americans that makes us unimpressed by Turkish Delight. There’s nothing exciting about a super-sweet gel, since we pretty much live on super-sweet gel from birth. Or maybe, for the millions of us who read The Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe (the Narnia series has sold over 100 million copies worldwide), it’s the way we build it up inside our brains, imagining it as the ultimate candy or maybe even the most delicious turkey.

One thing is clear: If any of the various Narnia portals make their way across the pond, the White Witch will have to diversify. Over here, we can maintain our integrity in the face of sugar and rosewater gelatin. We’ll only consider selling out our families for marshmallows. Or baklava. Or stuffing, chocolate truffles, pink Starburst, nougat, Watchamacallit bars, or cotton candy. Narnia is doomed.

Update, 12/3/15: We originally referred to Bekir Effendi as “Effendi,” but that’s an honorific, not a last name. We’ve changed it to “Bekir” throughout.

*Correction: This post previously described Turkish Delight as made from gelatin. Traditional Turkish Delight does not use gelatin, but corn starch.

This story originally ran on December 3, 2015.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook