Ancient Egyptians May Have Spiced Their Mummies

Most ingredients in embalming perfumes were good enough to eat.

THIS ARTICLE IS ADAPTED FROM THE OCTOBER 21, 2023, EDITION OF GASTRO OBSCURA’S FAVORITE THINGS NEWSLETTER. YOU CAN SIGN UP HERE.

When Dora Goldsmith, a PhD researcher working on her doctorate thesis in Egyptology at Freie Universität in Berlin, wanted to know what newly deceased ancient Egyptians smelled like, she took an unorthodox approach: She partially mummified herself.

Goldsmith had translated four recipes for ancient fragrances, including a Ptolemaic recipe for a burial perfume carved on the wall of the Temple of Edfu on the west bank of the Nile, as well as an embalming perfume, written on an Eighteenth-Dynasty papyrus currently residing in the Louvre Museum. The latter was intended to be rubbed onto the corpse and burial bandages shortly after death.

“It perfumes the body and it also preserves the body,” she explains. To find out just how, in August 2023, Goldsmith took the resinous, charcoal-tinted mixture, painted it onto her own arm and wrapped it in bandages. The only problem? Removing it took some serious scrubbing. “I managed to mummify myself and it didn’t come off,” she says with a laugh. Luckily, she didn’t mind the scent of death much at all. “It smells really good, really smoky,” she notes.

Part of the reason these long-lost embalming and burial perfumes smelled so delicious is most of their ingredients were actually pretty tasty. “Almost everything that the ancient Egyptians used in their perfume was edible,” Goldsmith says. “Perfumes in ancient Egypt were often very versatile. You could eat them, chew them, fumigate them, or wear them on your skin, hair and clothing.”

Thanks to a mix of archeological evidence and written historical records, we have an idea what might have slathered on mummies. Honey, yogurt, juniper berries, carob juice, dates, and beef tallow were all integrated into perfumes or placed onto corpses. Frankincense and myrrh, for instance, were chewed as gums throughout the region, in addition to being used as costly perfumes. Less sweet-smelling edibles also made their way into the mix, including garlic cloves and onions. The skins for the latter were often used as surrogate eyelids. In one case, says Goldsmith, a whole onion was wedged directly into a mummy’s armpit.

To cleanse the bodies, ancient Egyptians washed them in the finest booze available. “It actually all sounds very fancy, doesn’t it?” Goldsmith says. “They bathed the corpses in wine and beer.”

Whether or not certain spices were used is decidedly more controversial among modern-day Egyptologists. For instance, ancient Greek historians Herodotus and Diodorus Siculus claimed that cinnamon was a common aromatic in the embalming process. Yet Egypt didn’t establish trade routes to India, where Cinnamomum verum grows, until the third century BC, near the end of the Pharaonic era.

Coumarin, an aromatic compound found in cinnamon, has been discovered on mummies, but that’s not conclusive. “There’s one pre-dynastic body that seemed to have cassia on it, but they have since done a reanalysis, and it has cinnamyl alcohol,” says Nuri McBride, a researcher and perfumer who explores the topic in Death/Scent, an academic blog on the use of fragrances in death rituals.

As she points out, however, that specific compound could also have come from cloves. “Language gets really tricky because even in the Middle East, we’re looking at Aramaic, we’re looking at Hebrew, we’re looking at old Arabic,” McBride says. “They switch terms because all they’re getting is a nice brown powder from far away, and they don’t necessarily know what it is. Is it clove? Is it cinnamon? Is it cassia? Is it nutmeg? Is it mace? Is it all five mixed together?”

Other spices definitely made their way to the land of the pharaohs. Ramses II, who died in 1213 BC, was buried with peppercorns jammed up his nostrils, “The Egyptians really did not have these trade contacts with India [at that time], so it was something truly special,” Goldsmith says. “The idea behind it is that Ramses II would smell something pleasant all the time in the afterlife.”

In ancient Egypt, scent was a powerful signifier of class, both in life and after death. Since relatives wanted their loved ones to have the best possible existence in the afterlife, they tended to spend as much on the embalming process as their budgets allowed. For the families of the departed, this decision had deeper olfactory implications.

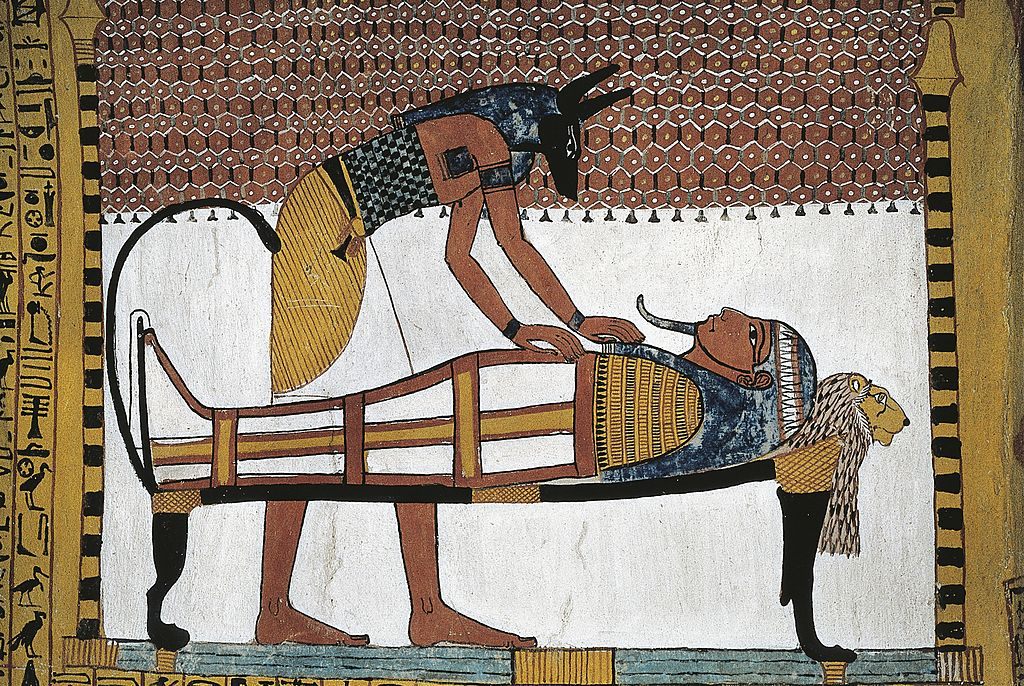

“There’s this association between scent and identity in ancient Egypt where the way that you smell marks your status, how wealthy you are, or how respected you are,” says Robyn Price, a postdoctoral research associate in the Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology and the Ancient World at Brown University. In some instances, scent even signaled divinity. “They talk about the deceased taking on the scent of the gods so that they will then be accepted and welcomed by them in the afterlife. So by actually smelling divine, you become divine in a way.”

The rather gruesome spectacle of natural decay was not lost on the ancient Egyptians. The Book of the Dead, which dates back to 1550 BC, features a number of rather visceral descriptions. “One reads, ‘The bones are softened, and the flesh is a stinking mass. He reeks, he decays, and turns into a mass of worms. Nothing but worms,’” Price says. “They are very aware of what happens when you die and your body decays, and they’re actively fighting against that to give you this positive scent so that you will be welcomed into the afterlife.”

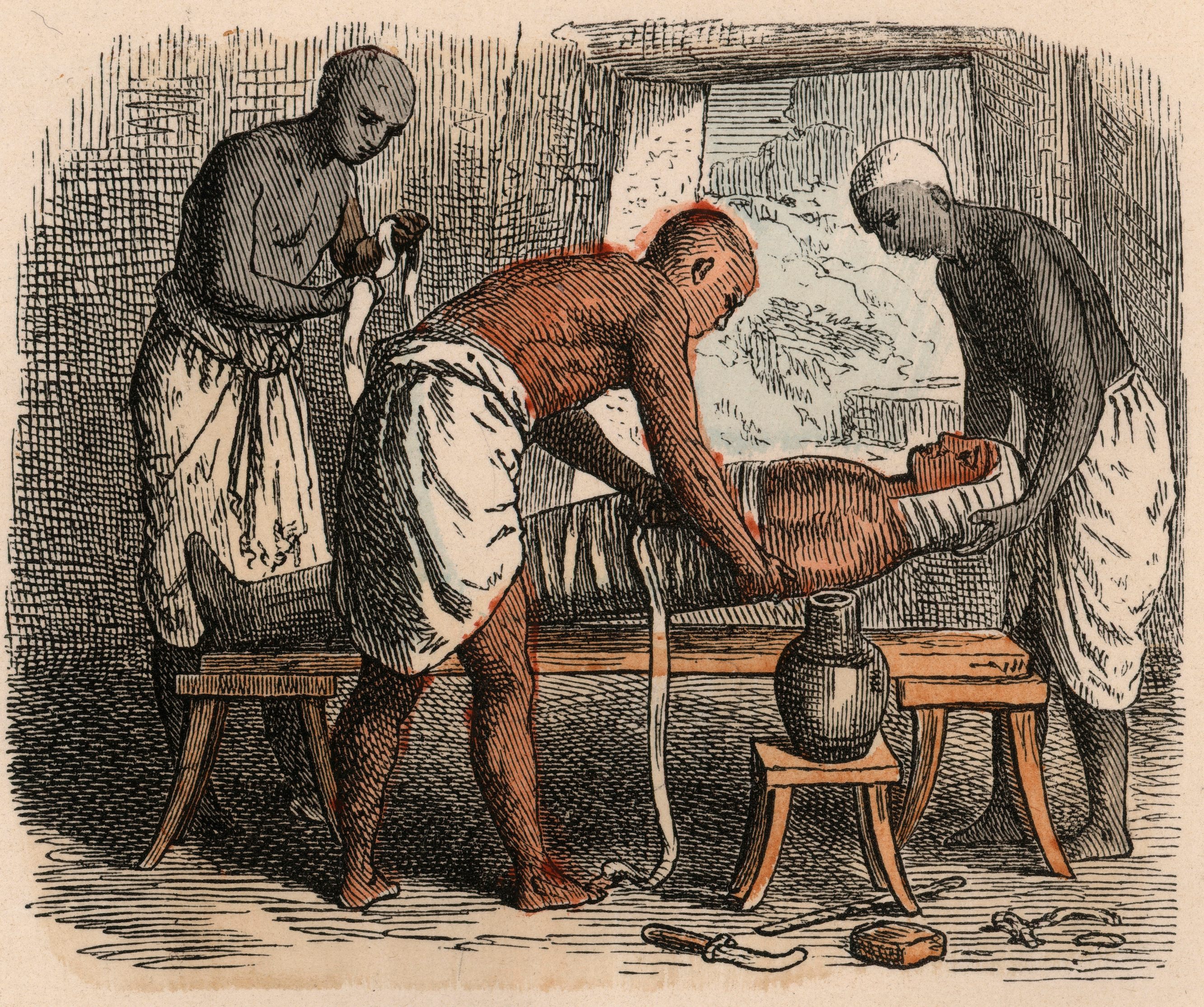

The ancient Egyptians were exceptionally skilled at keeping the worms at bay, first removing fluids and organ tissue, using natron salts to further desiccate the body, and finally applying resins and oils to keep insects at bay. “Part of this ritual embalming process was to equip the deceased body with a positive smell, because the negative smells of death and decay could actually damn your soul,” Price explains.

Living relatives would have spared no expense when it came to fragrances. Price points out that almost all of the gums, resins, oils, and fragrances used in embalming came from outside of Egypt, rendering them especially costly. While lower-class burials tended to be on the simpler side, pharaohs and nobility would be anointed with the finest fragrances money could buy.

What we do know for sure is that these ingredients, some of which traveled thousands of miles over land would have represented an earthly fortune—something the ancient Egyptians were all too ready to give to the dead. That bodies were laid to rest smelling like nobility is a testament to the love and grief of the families.

For Goldsmith, her present-day experiments in perfume-making proved an unusual way of bonding with her still very much alive family. In addition to painting the embalming fragrance mixture on herself, she added it to her father’s arm. While she asked if he’d like to be mummified someday, he quipped, “Honey, I’m still here!”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook