The Messy History of Emily Dickinson’s Black Cake Recipe

It reveals an unexpected side to the poet’s personality and the brutality that brought a Caribbean dish to New England.

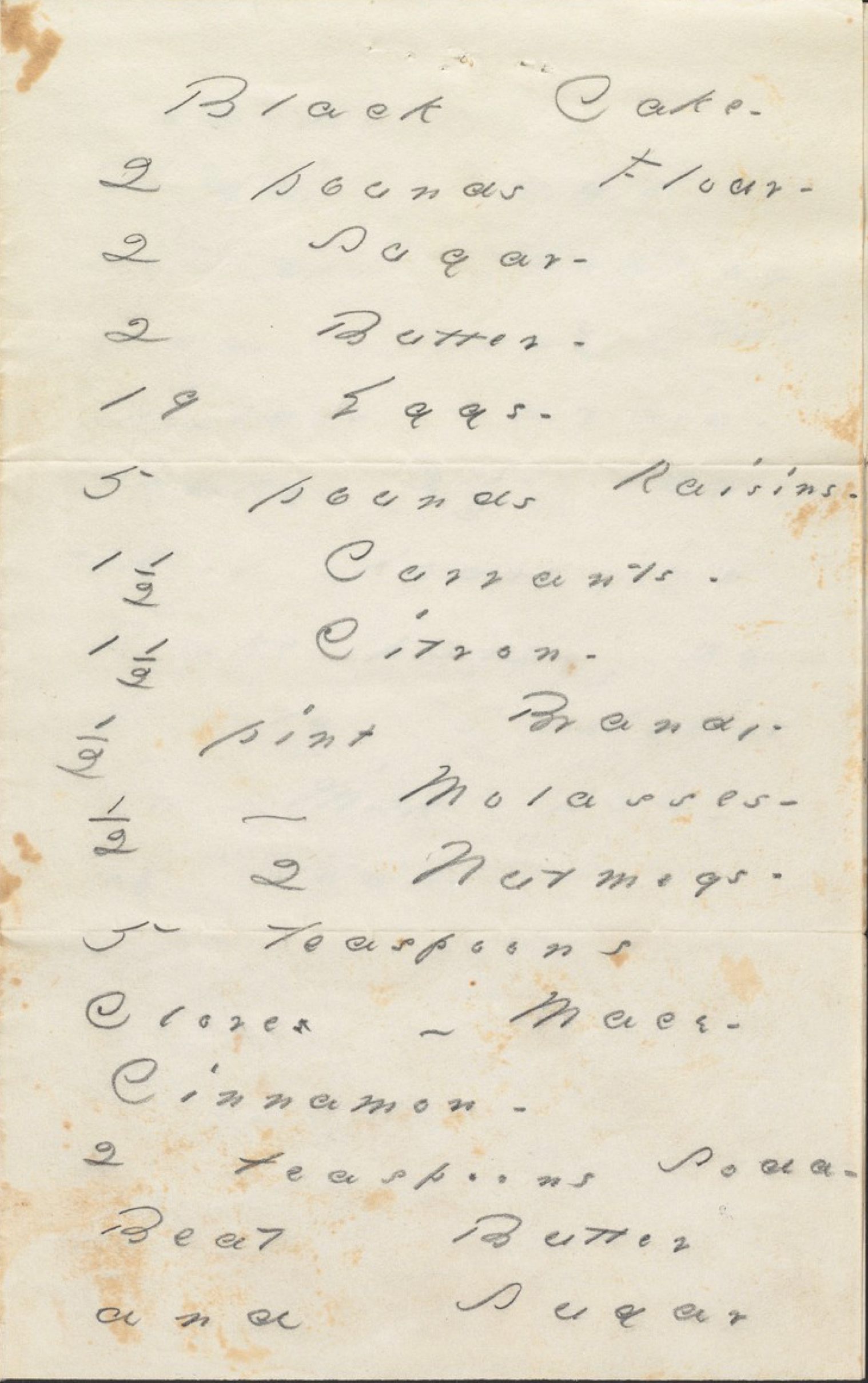

In the dark pandemic days of last December, 667 people gathered on a video call to celebrate Emily Dickinson’s birthday—and her black cake. Participants were invited to bake the recipe before the gathering, and many appeared on camera with their own rendition of the cake. The tradition had started five years before, when Emily Walhout, a reference assistant at Harvard University’s Houghton Library—which houses the largest collection of Dickinson’s poems, letters, and household artifacts in the world—finally decided to bake the poet’s recipe. The library owns Dickinson’s handwritten original recipe, from a letter she sent to her friend Nellie Sweetser. “I had been at Houghton for decades, knowing about this recipe and wondering why nobody made it,” Walhout says. When Emilie Hardman, a former pastry chef, joined the staff, she and Walhout decided to go for it.

Black cake is a Caribbean Christmas cake, piquant with spirits and velvety with molasses or burnt sugar. Dickinson’s recipe, written in loopy letters on age-yellowed paper, belies her biography: A dedicated baker, Emily was better known during her lifetime for her desserts than her poetry. The labor-intensive recipe, and its journey from the Caribbean to Dickinson’s elite New England milieu, reminds us of the brutal histories of colonization and enslavement that shaped her times, and the Black and immigrant domestic laborers who shaped her work and home. Dickinson’s black cake recipe also helps us reimagine Emily herself—not as the austere recluse the patriarchal literary establishment has long portrayed, but as a sensuous, socially connected woman who shared poems and cakes with family, friends, and her life-long queer love.

A relative of British fruit cake, black cake depends on the sugar English colonizers forced the Indigenous and African people they enslaved to produce. The Caribbean version of the cake usually includes rum and either molasses or burnt sugar, also known as browning, a bitter liquid that results from scalding white sugar over a high flame. “You can taste the slight bitterness at the back of your throat,” says Canadian poet M. nourbeSe philip, who wrote an essay on Dickinson’s black cake. For many Caribbean families, preparing the cake is a joyful annual tradition. philip watched her mother bake the cake growing up in Trinidad and Tobago. After she immigrated to Canada, her mother shipped her a homemade black cake every year.

The recipe and its ingredients were likely brought to New England from the Caribbean along the horrific triangular trade. Dickinson’s version uses molasses and swaps the rum out for brandy. Both Dickinson’s and Caribbean recipes are dense with dried fruit, including raisins, currants, and candied citron in Dickinson’s case. And they’re fragrant with nutmeg, cinnamon, and mace, brought to the Caribbean by colonizers from the spice coasts of Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Malabar.

Since black cake is meant to be shared, recipes can be massive. Dickinson’s calls for two pounds of butter, 19 eggs, and five pounds of raisins; the assembled batter, according to the Houghton staff, weighs 20 pounds. Basted with brandy, the cake keeps for months, if not until next Christmas.

Making the cake at the yearly Houghton gathering, says Christine Jacobson, assistant curator of modern books and manuscripts, summons an atmosphere of “warmth and conviviality.” Dickinson’s recipe, worn from years of use, brings the poet to life. “It’s stained, it’s imperfect, you can tell it was written in haste,” Jacobson says. Dickinson frequently gifted recipes—including the black cake recipe—and baked goods to friends, and the quantity of batter in her recipe means that she likely made it alongside her sister and household domestic workers, according to Dickinson scholar and artist Aífe Murray. This lively image of the poet rolling up the sleeves of her white frock to mix 20 pounds of batter, air redolent of cinnamon and mace, is a stark contrast to the otherworldly Emily Dickinson the literary establishment has long depicted.

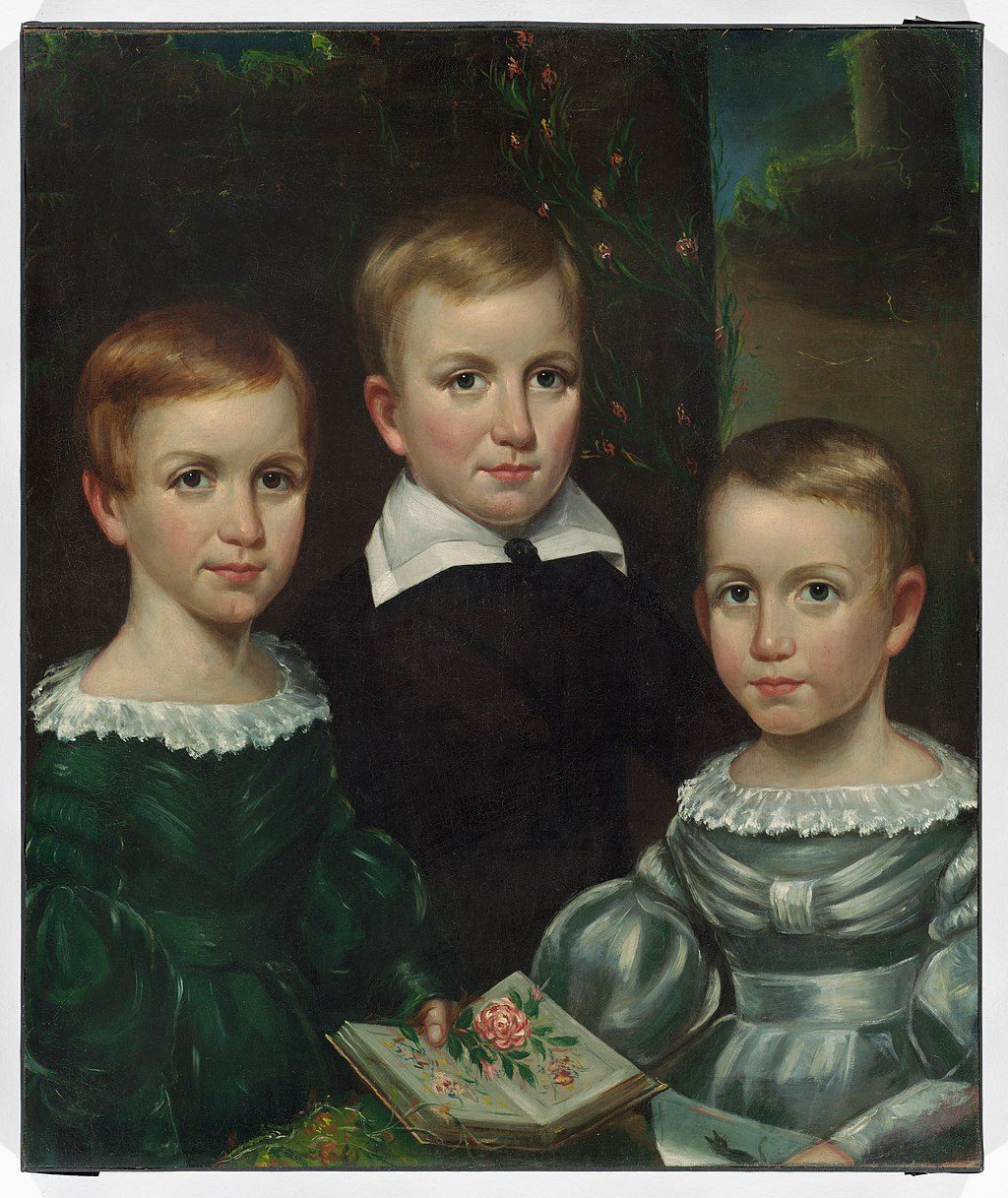

Emily Dickinson wrote almost 1,800 poems, but she published only a few in her lifetime. She was a known baker but an obscure poet. She never chose to marry, instead living in her father’s farmhouse in Amherst, Massachusetts, until she died. She rarely took visitors, choosing to appear occasionally at her bedroom window as she lowered baskets of her famous gingerbread to village children.

For nearly a century after her death, literary scholars—with the help of Mabel Loomis Todd, who edited Dickinson’s work after her death and also happened to be her brother’s mistress—overwhelmingly chose to interpret those facts in the most severe way possible. They depicted Dickinson’s reticence as self-effacement, her singleness as chastity, and her reclusiveness as dainty misanthropy.

According to Martha Nell Smith, a Dickinson scholar at the University of Maryland, this waifish image was largely late-Victorian propaganda. “You know how we have the image of a rock star: sex, drugs, rock and roll?” she asks. In the late 19th century, “The composite biography of a woman poet is that she bore a secret sorrow, that she was reclusive, and that she probably dressed in white. Sound like anybody you’ve heard of?”

In the past three decades, scholars like Smith have urged us to look past the myth of the woman in white to see Dickinson as she depicted herself: sensual, at times rebellious, and effervescently queer. This version of Dickinson is evident throughout her work. Her poetic voice often shifts between genders. She expresses both intense desire (“Might I but moor - tonight -/ in thee!” she writes in “Wild nights - Wild nights!”) and powerful declarations of autonomy (“I’m ceded - I’ve stopped being Theirs,” she writes in poem 508).

Pointing to this self-possession, scholars like Smith argue that Dickinson chose to stay home in order to prioritize her work. They note that her vigorous correspondence, with dozens of interlocutors over decades, shows she was far from socially isolated. And they emphasize the centrality of Emily’s lifelong relationship with Susan Gilbert Dickinson, the poet’s sister-in-law, next door neighbor, primary editor—and likely lover.

While Dickinson scholars had long acknowledged that Emily and Susan were friends, Smith’s 1998 book, Open Me Carefully, included a stunning revelation. Going back through Dickinson’s letters, Smith discovered places where Mabel Loomis Todd had literally cut up and smudged out words. The most commonly erased and altered items: she/her pronouns in letters and poems to Sue, and affectionate lines about Sue.

We can’t say for sure why Todd erased these lines, though Victorian respectability is a good bet. As, says Smith, are personal resentments: Mabel Loomis Todd was having an affair with Emily’s brother Austin Dickinson, who was married to Susan, who in turn was likely having an affair with Emily.

Many of those obscured lines were breathtakingly erotic. Reading the letters in Open Me Carefully, one can almost feel the electricity: “Sweet Sue, / There is / no first, or last, / in Forever - ” one letter-poem starts. In the same poem, she continues, “for the Woman / whom I prefer, / Here is Festival - / Where my Hands, / are cut, Her / fingers will be / found inside.” In another letter to Sue, she writes “We are the only poets. And everyone else is prose.”

Emily’s passion for Sue, poetry, and baking were intertwined. Dickinson spent hours each week making bread and cake for her father’s household. “She certainly was writing in the kitchen on scraps of paper,” Smith says. Some extant Dickinson manuscripts are decorated with food stains, including likely splatters of currant wine, an Emily specialty. Dickinson left several handwritten recipes among her papers, and their line breaks bear the same telltale dashes of her poetry. Meanwhile, the open-ended form of Dickinson’s poems sometimes mimics the terseness of a recipe. They’re “recipes for reading,” Smith says.

Dickinson frequently shared her baked goods with friends, along with flower cuttings and affectionate letters. “I enclose Love’s ‘remainder biscuit,’ somewhat scorched perhaps in baking,” she wrote a friend, alongside a gift of slightly burnt caramels. “But ‘Love’s oven is warm.’”

Dickinson’s greatest correspondent was Sue, who often edited Emily’s work. In one exchange, Susan thanks Emily for a bouquet (“The flowers are sweet and bright and look as if they would kiss one”), complains about making a bib for her child, and provides feedback on Emily’s draft of “Safe in Their Alabaster Chambers.” In another exchange, when Susan is away teaching, Emily mails her rice cakes amid a series of passionate love letters.

Food also appeared, in vividly sensuous language, in dozens of Dickinson’s poems and letters. “I taste a liquor never brewed - / From tankards scooped in pearl,” she writes in poem 214. In her letter-poems with Sue, food and drink appear to stand in for devotion and longing. “I could not drink it, Sue / til you had tasted first – / Though cooler than / the Water – was / The Thoughtfulness of / Thirst,” Dickinson writes in one letter-poem. In Sue’s obituary for Emily, she mentions “Emily’s ambrosial dishes.” “I was like, ‘That is sexy! Because that emphasizes taste and smell,’” says Smith, laughing.

Recently, Smith’s work, and that of other feminist Dickinson scholars who’ve brought the poet’s sensuality and sexuality to light, has won public opinion. Since 2016, two popular films and a TV show (a whimsical, highly aestheticized teen drama) have all depicted the poet as queer. Meanwhile, fans and critics point out that Taylor Swift’s album Evermore contains allusions to the Emily-Sue relationship.

Yet if Dickinson’s black cake recipe helps us reimagine her as a social and sensual being, it also forces us to contend with histories of injustice she benefited from.

A few years ago, philip’s family had just picked up their annual Christmas black cake when she heard about Dickinson’s black cake recipe on the radio. “I was just stunned,” she says. “It was just this moment of, ‘No, those two things don’t go together.’” philip thought of her own mother, who also made black cake, but who—unlike the elite white poet—had days so filled with care-taking and laundry, she was left with no time to make art. philip quickly realized that the two were, in fact, connected, through the brutal historical trade in sugar, rum, and enslaved African people on whose forced labor American wealth rests.

The elite Dickinson family, like all white Americans, economically benefited from slavery. Their ancestors were early New England colonizers, and their Southern enslaver cousins fought for the Confederacy. Emily’s congressman father, Edward, was not an abolitionist. Dickinson’s own letters, meanwhile, contained violently anti-Black and anti-Irish statements. Her brother, Austin Dickinson, was part of the xenophobic Know-Nothing party.

Conventional histories of Dickinson, as of other white poets, tend to gloss over this complicity. “She’s removed from this very messy, ugly context and held as this beacon, this symbol of purity,” philip says. But in her essay “Making Black Cake In Combustible Spaces,” philip argues that the very ingredients of black cake, especially the bitter burnt sugar, implore readers to confront these often-erased histories—and challenge them to imagine more just futures. “We have to remember the bitterness,” she says. “It’s what gives the cake the sweetness.”

Dickinson’s black cake recipe also reminds us of the Black and Irish domestic workers who helped make her family’s household run. Though they could afford to hire full-time domestic workers, the Dickinsons employed only part-time workers when Emily was young, expecting Emily, her mother, and her sister, Lavinia, to do most of the housework. Emily complained about the incessant demands of domestic labor.

The family eventually employed a long-term Irish maid named Margaret Maher. Emily became close to Maher, who lived and worked at the Dickinson house for over thirty years. It’s likely the two baked together—including, perhaps, the black cake, says Aífe Murray, who wrote a book documenting the influence of Black and Irish workers on Emily’s poetry. These workers’ labor freed up Dickinson’s time, so she could pursue poetry. Meanwhile, Murray argues, their ways of speaking likely shaped Emily’s ear for language, contributing to the unique cadence of her poems. Emily actually stored her manuscripts in Maher’s trunk, and according to one family source, Maher was instrumental in saving those manuscripts from incineration after Dickinson’s death. Yet Maher has largely been edited out of Dickinson histories. “Dickinson’s ‘voice,’ in a sense, had depended on Maher’s ‘silence,’” Murray writes.

The black cake recipe helps us understand the aspects of Dickinson’s life and poetry—her passion, her queerness—that were literally erased. But it also reminds us of these other erasures, of the people whose unrecognized labor helped make Dickinson the great poet we know today. The messy history of black cake asks us to challenge the conventional image of Emily Dickinson as a waif in a spotless white dress. It asks us to imagine, instead, the dress’s fabric sticky with molasses, rumpled with the labor of baking, and splashed crimson with currant wine. It asks us to imagine the indigenous land that grew the dress’s cotton, the enslaved Black people who were forced to pick it, the immigrant laborers who spun it into fabric, and the Irish laundress who boiled and beat that dress until history could pretend it had always and only been white.

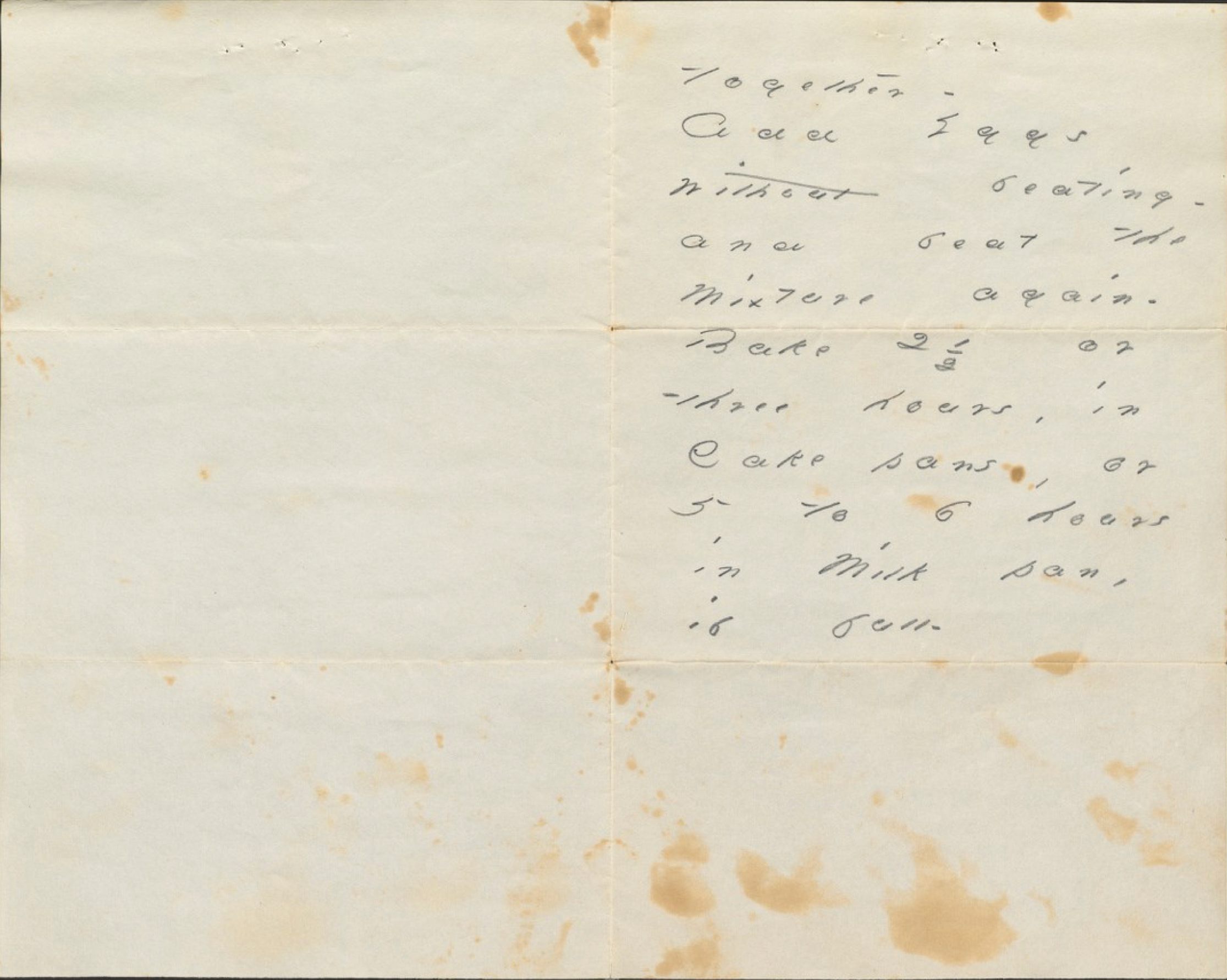

Emily Dickinson’s Original Black Cake Recipe

You can find the original manuscript, and a video of the first Houghton recreation.

2 pounds Flour -

2 sugar -

2 Butter -

19 Eggs -

5 pounds Raisins -

1 ½ Currants -

1 ½ Citron -

½ pint Brandy -

½ — Molasses -

2 Nutmegs -

teaspoons

Cloves - Mace -

Cinnamon -

2 teaspoons Soda -

Beat Butter

and Sugar

Together -

without beating

and beat the

Mixture again -

Bake 2 ½ or

Three hours, in

Cake pans, or

5 to 6 hours

in Milk pan

if full.

Houghton Library’s Version

A quarter of the original size, courtesy of Emily Walhout and Houghton Library.

8 ounces (227 grams) flour

8 ounces (227 grams) sugar

8 ounces (227 grams) butter

5 eggs

20 ounces (570 grams) raisins

6 ounces (170 grams) currants

6 ounces (170 grams) citron

2 ounces (60 milliliters) brandy

2 ounces (60 milliliters) molasses

half a nutmeg, grated (roughly 1¼ teaspoon grated nutmeg)

1¼ teaspoon cloves

1¼ teaspoon mace

1¼ teaspoon cinnamon

½ teaspoon baking soda

- In a small bowl whisk together the flour, spices, and soda.

- In a large bowl, cream the butter and sugar.

- Mix in the unbeaten eggs until blended, then mix in the brandy and the molasses.

- Add the dry ingredients and mix well.

- Add the raisins, currants, and citron, and mix until the fruit is well-distributed.

- Pour the batter into a greased 9 x 13 inch (23 x 33 cm) baking pan lined with parchment paper. Bake at 250 ºF (120 ºC) for three hours. After allowing it to cool, wrap the cake in a cheesecloth soaked in brandy. Store it in an airtight container in the fridge.

- Every once in a while over the coming weeks and months, baste the cake with more brandy. The cake can be eaten any time after it emerges from the oven, but the longer you store it, the tastier it will be.

Gastro Obscura Tips

- You can compare Dickinson’s black cake recipes to various Caribbean black cake recipes online. M. nourbeSe philip includes an image of her mother’s black cake recipe in “Making Black Cake in Combustible Spaces.” She notes that her mother’s recipe calls for two pounds of butter, like Dickinson’s, and 24 eggs, more than Dickinson’s. Her mother’s burnt sugar was homemade.

- You can play around with the dried fruit. Citron can be hard to get ahold of; you may have to order it online. You can also buy or candy your own lemon or orange peel. I opted to use currants and raisins in the proportions named above, plus mixed candied fruit and honeyed lemon peel from a Caribbean grocery store.

- Caribbean black cake recipes, as well as many British fruit cake recipes, advise soaking the dried or candied fruit in liquor for anywhere from a couple hours to half a year before making the cake. You can substitute burnt sugar, also called browning, for the molasses, and rum for brandy; consult the Caribbean recipes above for tips on the proportions. You can also try adding mixed essence, a sweet and fruity flavoring extract; again, follow recipes from Caribbean chefs.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook