Can Nostalgia Save Oregon’s Beloved Psychedelic Theme Park?

Here’s how the scrappy Enchanted Forest is struggling to survive the pandemic.

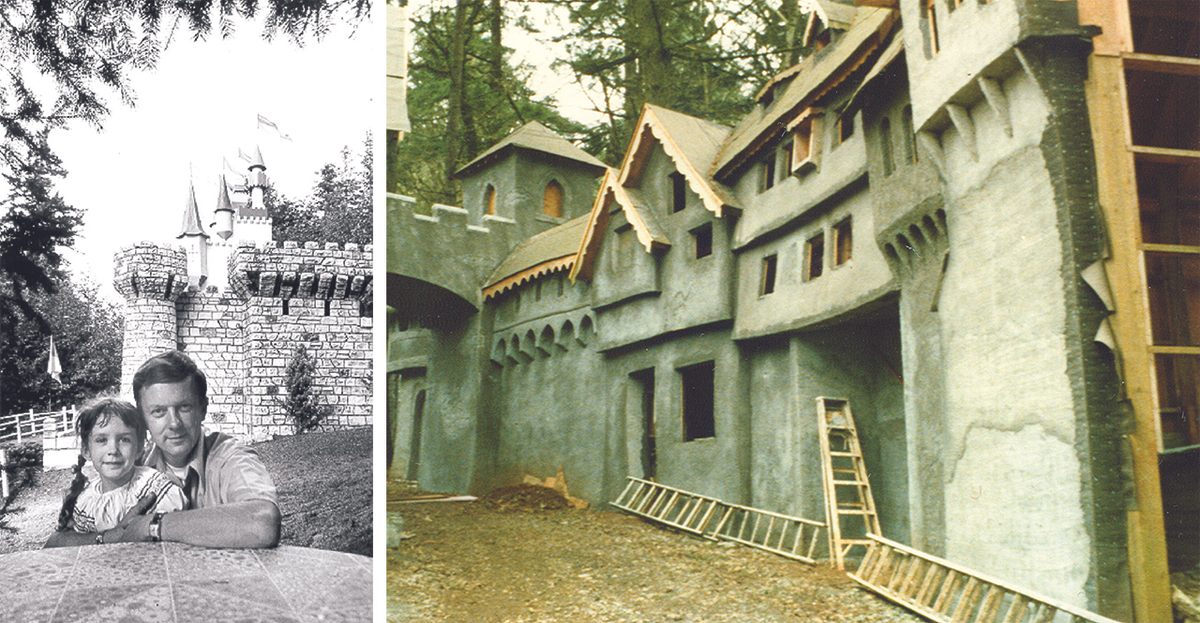

Off a seemingly sleepy exit on Interstate 5 in Oregon sits a trippy theme park. Enchanted Forest, which has occupied 20 acres on a hill in the woods between Portland and Eugene for 49 years, is what Disneyland might look like if it had been designed by Ken Kesey and filled with 1960s-era sculptures and animatronic relics of fairy tale characters. It’s unpolished, charming, non-corporate. To some, it’s a beloved family attraction in an otherwise rural area; to others, it’s a slightly creepy but fascinating drug playground in a state where weed is legal and psychedelics are easily accessible. Since the park opened in 1971, it’s been family-run, with no debt. But the COVID-19 pandemic, coupled with a summer of raging wildfires, has changed things.

Susan Vaslev co-manages the park and is a daughter of its founder and builder, Roger Tofte. Even over Zoom, you can see her breath in the November air as she dodges piles of wet leaves and steps over red tape marking six-foot distancing requirements. She’s walking along Story Book Lane, the park’s Douglas fir-lined main path, where on a normal summer day, thousands of visitors walk by sculptures of Humpty Dumpty and Little Red Riding Hood’s Cottage or stream into the gaping mouth of the Snow White witch, whose skin is painted like a tree trunk.

This year, nobody rode the slide built into the boot that houses the “old woman who lived in a shoe,” and now Humpty Dumpty is covered with a tarp. The parking lot is empty, which it was for most of the summer, with no need for the overflow lot or shuttle. The only people on site are members of the Tofte family. Vaslev’s uncle rides around in an ATV doing maintenance, and the log ride brims with leaves and rainwater. It’s normal for the park to be sleepy this time of year; it closes up for the winter. But this year, there’s no guarantee that thousands of guests will ever walk down Story Book Lane again.

This year, because of state regulations around COVID-19, the park wasn’t able to open until June, the midpoint of a typical season. Then, when it finally opened, state officials limited capacity to 250 people, including employees. That left room for only 200 visitors at a time, compared to the thousands of visitors the park typically sees. The state rejected Vaslev’s request to host private tours before June, as well as her requests to allow a higher occupancy, given the park’s sprawling size.

In addition to the pandemic, one of Oregon’s worst fire seasons on record caused the park to close for the first weekend in September, stunting its already short season. (Its last weekend is at the end of September.) Fires never reached the park, nor did falling embers, but blazes cast an eerie red light over everything, as if Humpty was in hell. The Tofte family also suffered a devastating loss of two family members to the fires.

“It’s a rollercoaster,” says Vaslev. “Initially we were really positive, like, ‘There’s gotta be a way.’ As you mentally see this really mushrooming into a huge financial mountain to overcome, there are days when I’ve been crying.”

Amusement parks are precariously positioned in a pandemic: They’re nonessential businesses full of high-touch surfaces and, ideally, massive crowds. Oregon’s only other amusement park, Oaks Park in Portland, was closed all summer, and closed again only a week after opening its skating rink in early November. But despite being deemed nonessential, small, nostalgic businesses are important to the people who have a connection to them. It’s that nostalgia that may save Enchanted Forest right now.

In October, Vaslev put up a GoFundMe page asking for half a million dollars to get them to the spring 2021 season. More than $250,000 poured in within two weeks. The funds will go to insurance, payroll and health insurance for the staff the owners were able to retain, property taxes, roof and dry rot repairs, ride maintenance, and utilities. “We didn’t think anyone would donate other than a few people,” says Vaslev. “You’ve been working alone all these years and to see all that community support is really wonderful.” In early December, the page reached $350,000, which Susan believes will get them to the 2021 season.

When Tofte bought 20 acres of land and vowed to build an amusement park by hand, he said some people dubbed the project “Idiot Hill.” But decades later, a community of past, present and future Enchanted Forest generations are rallying. Several weeks into the fundraiser, more than 6,700 people have donated.

“I grew up not very privileged. I’ve never been to Disneyland. Enchanted Forest was my place,” says Abby Hufford, 36, who donated to the GoFundMe and estimates she’s visited at least 35 times. When her sister got married, Hufford suggested Enchanted Forest for the honeymoon. “I go every chance I get. I just love that place, the smell of it, everything about it is just childhood,” she says. “I love how it’s essentially been the same my entire life. It would be traumatic to lose Enchanted Forest.”

Alongside the GoFundMe, the park is auctioning off Tofte’s original artwork, signed prints, and blueprints. “We never intended to let anything go,” Vaslev says. “I think it’s harder on me than it is on my father because that’s our memories, but it has to happen. We’re hoping we don’t have to auction off everything.”

Vaslev believes the park will make it to the next season, but is worried about what will happen the grounds can’t open at full capacity in the spring. “You can’t continue to lose money indefinitely,” she says. “How long is it possible for it to go on? How long will people continue to help support you?”

Some small business owners worry that, over the course of the pandemic, more and more independent businesses will shutter, leaving a landscape of only Olive Gardens and Disneylands. For Vaslev, the loss would be “like losing a member of the family.”

“It’s once in a lifetime. My father created it from the ground up,” she says. “If we lose it, nobody’s going to be able to reproduce it. It’s impossible.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook