Britain’s Secret Theft of Ethiopia’s Most Wondrous Manuscripts

Plundered in 1868, they are kept at the British Library—and an ongoing campaign seeks to bring them home.

In the basement of London’s British Library I was led into a small well-lit room, marking the end of a journey that began in the Ethiopian Highlands at the Addis Ababa home of a remarkable British historian.

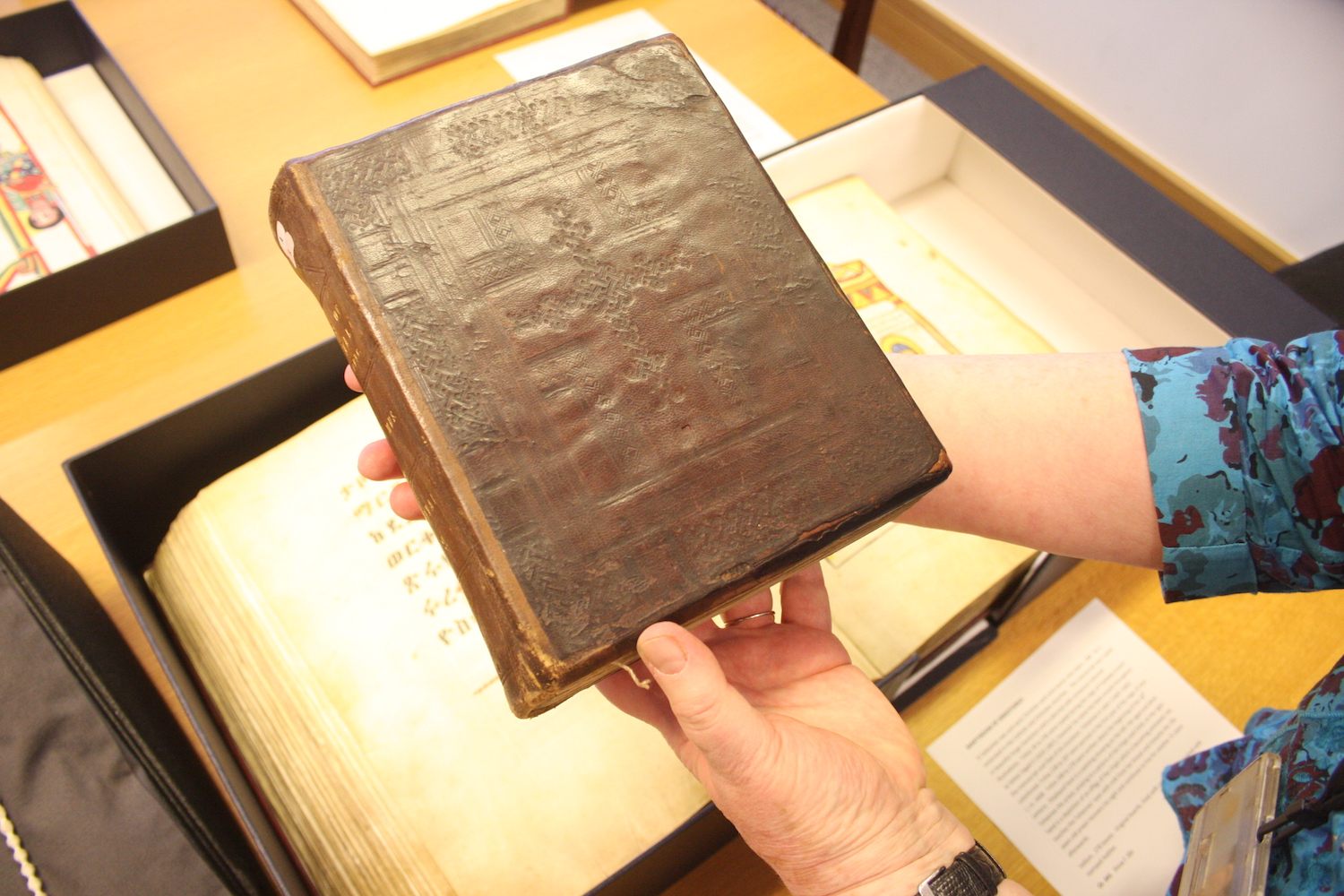

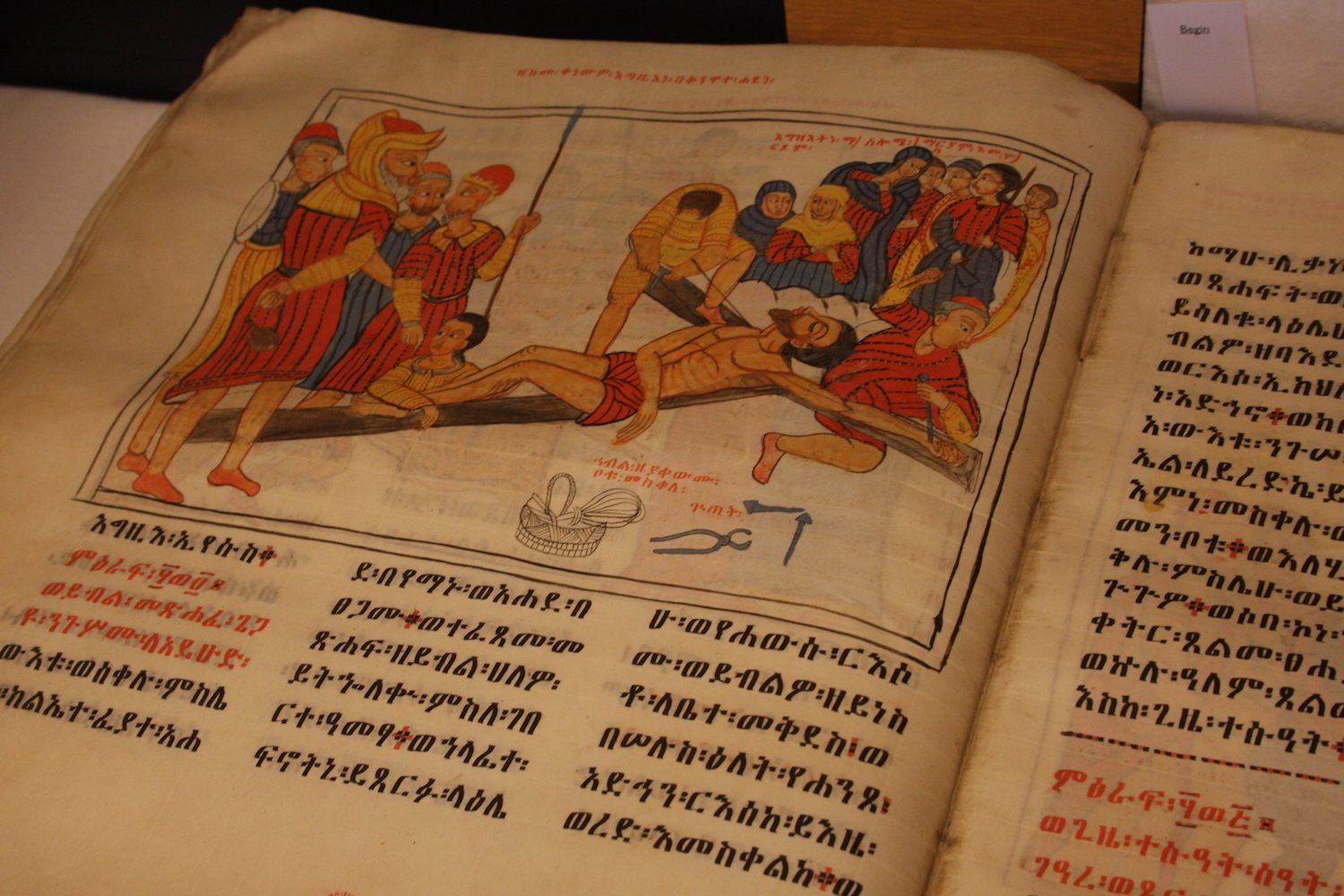

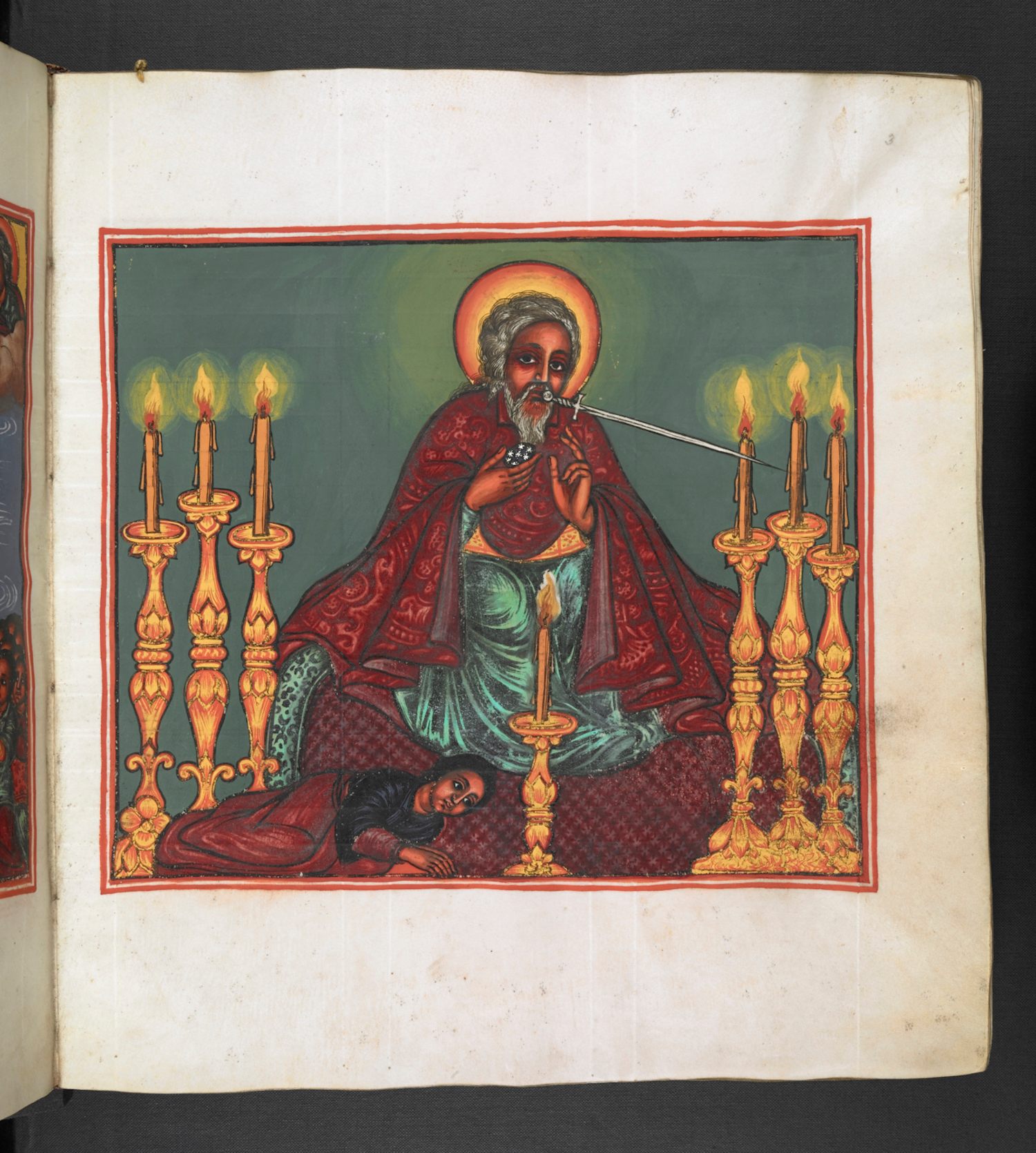

In that home, over strong Ethiopian coffee and English biscuits, Richard Pankhurst, who dedicated his life to documenting Ethiopian history, told me the story of the ancient manuscripts looted at the end of the Battle of Maqdala. In 1868, a British expeditionary force laid siege to the mountain fortress of Ethiopian Emperor Tewodros in what was then Abyssinia. A two-day auction of the spoils of war among the victorious troops resulted in more than a thousand predominantly religious manuscripts making their way to Britain—15 elephants and hundreds of mules carried them along with other cultural treasures to the coast—with 350 manuscripts ending up in the British Library. Pankhurst campaigned for the return of the manuscripts to Ethiopia but hadn’t succeeded before his death in 2017. Now other voices are continuing the cause.

“It’s true that the level of care and quality in Britain is much better than ours, but if you come to the Institute of Ethiopian Studies where we have a few Maqdala items previously returned you can see how well they are kept and made available to the public,” says Andreas Eshete, a former president of Addis Ababa University—which houses the institute—and who co-founded the Association for the Return of the Ethiopian Maqdala Treasures (AFROMET). “These manuscripts are among the best in the world and one of the oldest examples of indigenous manuscripts in Africa, and they need to be studied carefully by historians here.”

But the British Library views its guardianship of the manuscripts for the sake of international research and access as equally necessary.

“We have the responsibility, as a public institution and national library, to research, make accessible and preserve the collections under our custodianship for people and researchers from all over the world, as well as encouraging and promoting international cultural exchanges,” says Luisa Mengoni, head of the library’s Asian and African Collections.

What all sides agree on is the manuscripts’ uniqueness. When I met Pankhurst his health was deteriorating but his eyes lit up whenever the manuscripts were mentioned.

“It is not widely known what happened,” said Pankhurst, recognized as arguably the most prolific scholar in the field of Ethiopian studies. “The soldiers were able to pick the best of the best that Ethiopia had to offer. Most Ethiopians have never seen manuscripts of that quality.”

In the British Library’s viewing room I saw nothing to contradict Pankhurst’s praise.

“They are so lavish as they were made for kings,” Ilana Tahan, lead curator of Hebrew and Christian Orient studies at the British Library, told me as she delicately turned the manuscripts’ pages, explaining the art and craft that went into producing them.

Tewodros had the country scoured for the finest manuscripts and collected them in Maqdala for a grand church and library he planned to build. Tewodros was actually a fan of the British, even hoping they would help develop his country and reaching out to them in 1862. But a perceived snub led to him imprisoning a small group of British diplomats in early 1864.

“Queen Victoria failed to respond to his diplomatic initiatives for increased ties between Great Britain and Ethiopia,” says Kidane Alemayehu, one of the founders of the Horn of Africa Peace and Development Center, and executive director of the Global Alliance for Justice: The Ethiopian Cause.

Diplomatic efforts to release the prisoners dragged on until 1867 when the British government finally lost its patience, tasking General Robert Napier to lead a rescue mission with a force of 32,000.

“There has never been in modern times a colonial campaign quite like the British expedition to Ethiopia in 1868. It proceeds from first to last with the decorum and heavy inevitability of a Victorian state banquet, complete with ponderous speeches at the end,” wrote Alan Moorehead in The Blue Nile. “And yet it was a fearsome undertaking; for hundreds of years the country had never been invaded, and the savage nature of the terrain alone was enough to promote failure.”

On Easter Monday, April 13, with the British victorious in the valleys surrounding his mountaintop redoubt Maqdala and about to launch a final assault, Tewodros bit down on a pistol—a previous present from Queen Victoria—and pulled the trigger.

In Ethiopia today, Tewodros remains revered by many for his unwavering belief in his country’s potential, while the looting of Maqdala continues to spur the activism of AFROMET and others.

“Though Richard was unsuccessful with the British Library manuscripts, there was the return of a number of crosses, manuscripts from private collections,” says his son, Alula Pankhurst, himself a historian and author. Alula Pankhurst notes that the family of General Napier recently returned a necklace and a parchment scroll to the Institute of Ethiopian Studies. “My father would have argued that the items should be returned as they were wrongly looted,” Alula Pankhurst says. “There is now the technology available to make copies [of the manuscripts] that are indistinguishable from the originals and microfilms mean that copies could be retained.”

But such technology is also seen by those at the British Library as a reason why the manuscripts can remain where they are.

“We have both a growing opportunity and growing responsibility to use the potential of digital to increase access for people across the world to the intellectual heritage that we safeguard,” Mengoni says. During the next two years the library plans to digitize some 250 manuscripts from the Ethiopian collection, with 25 manuscripts already available online in full for the first time through its Digitised Manuscripts website.

“The artwork suffers when it is digitalized, plus many of the manuscripts have detailed comments in the margins—there are many reasons scholars need to attend to the originals and which are not met by digital copies,” Andreas says.

For the manuscripts to return to Ethiopia, those at the library note, new legislation would have to be passed by British Parliament. Alula Pankhurst notes there already is a legal provision that human remains should be returned, though it doesn’t appear to have had much impact. Former Ethiopian President Girma Wolde-Giorgis made a formal request in 2007 for the return of the remains of Theodore’s son Alemayehu, who was taken to Britain aged seven to be looked after following his father’s death but died there aged 18 and is buried at Windsor Castle. The request was turned down, Alula Pankhurst explains, based on potential damage an exhumation might cause to the surrounding graves.

“The restitution of Ethiopian property is a matter of respecting Ethiopia’s dignity and fundamental rights—looting another country’s property and offering it on loan to the rightful owner should evoke the deepest shame on any self-respecting country,” Alemayehu says. “I’m optimistic that the British Government [will] take an exemplary action by undertaking the restitution of properties [taken] by its army at Maqdala to the Ethiopian people.”

In the meantime, other options treading a middle ground are beginning to be talked about more openly. Tristram Hunt, director of London’s Victoria and Albert museum, which is exhibiting 20 of its Maqdala artefacts to mark the 150th anniversary of the battle, says he is “open to the idea” of a long-term loan of the objects to Ethiopia, a move Alula Pankhurst says “would be a step in the right direction.”

![The front page of one of the Maqdala manuscripts given to the British Library, on which is written: Pres. [Presented] by H. M. the Queen [Queen Victoria] 21 Jan. 1869.](https://img.atlasobscura.com/jJTFepwjfN14wDGzSM0UBJGox8R2OptqOsXl16WUyQg/rs:fill:12000:12000/q:81/sm:1/scp:1/ar:1/aHR0cHM6Ly9hdGxh/cy1kZXYuczMuYW1h/em9uYXdzLmNvbS91/cGxvYWRzL2Fzc2V0/cy9iMWQ5YzE4M2Nk/YTM3MTkxZWZfMjAu/SlBH.jpg)

At the end of my viewing session at the British Library, the manuscripts were carefully boxed up and wheeled back to the secure basement—where they will remain for now, while the library looks at making them more accessible to the public through new exhibits and building the online repository.

“While some restitutionists may grumble that the majority of items have not been returned, much has been done to spread knowledge of their existence—and great artistry—to Ethiopian scholars, and to the world at large,” says Alexander Herman, assistant director of the Institute of Art and Law, an educational organization focused on law relating to cultural heritage. “This has been made possible by the willingness of the British Library to invest in this once-overlooked part of its collection.”

Nonetheless, says Kidane Alemayehu, “the return of the loot of Maqdala has been an ongoing battle for Ethiopians and others with a sense of history and justice.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook